***

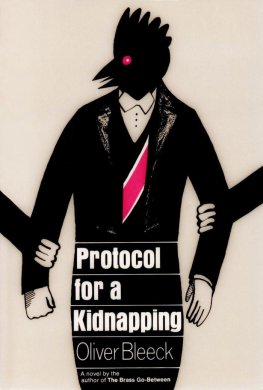

Kidnapping is a fact of life. Always has been, always will be. Extorting a ransom is an age-old pastime, less risky and more lucrative than robbing banks.

Kidnapping, twentieth-century style, has meant train loads and 'plane loads of hostages, athletes killed in company at Munich, men of substance dying lonely deaths. All kidnappers are unstable, but the political variety, hungry for power and publicity as much as money, make quicksand look like rock.

Give me the straightforward criminal any day, the villain who seizes and says pay up or else. One does more or less know where one is, with those.

Kidnapping, you see, is my business.

My job, that is to say, as a partner in the firm of Liberty Market Ltd, is both to advise people at risk how best not to be kidnapped, and also to help negotiate with the kidnappers once a grab has taken place: to get the victim back alive for the least possible cost.

Every form of crime generates an opposing force, and to fraud, drugs and murder one could add the Kidnap Squad, except that the kidnap squad is unofficial and highly discreet and is often us.

***ITALY

There was a God-awful cock-up in Bologna.

I stood as still as possible while waves of cold rage and fiery anxiety jerked at my limbs and would have had me pacing.

Stood still while a life which might depend on me was recklessly risked by others. Stood still among the rains of a success nearly achieved, a freedom nearly won, safety within grasp.

The most dangerous, delicate stage of any kidnap is the actual handing over of the ransom, because it is then, at the moment of collection, that someone, somehow, must step out of the shadows and a kidnapper comes to his waterhole with more caution than any beast in the jungle.

One suspicion, one sight or glint of a watcher, is enough to send him scuttling away; and it is afterwards, seething with fright and in a turmoil of vengeful anger, that he can most easily kill. To bungle the drop is to escalate the threat to the victim a hundredfold.

Alessia Cenci, twenty-three years old, had by that time been in the hands of kidnappers for five weeks, three days, ten hours, and her life had never been closer to forfeit.

Enrico Pucinelli climbed grim-faced through the rear door of the ambulance in which I stood: a van, more accurately, which looked like an ambulance from the outside but whose darkly tinted windows concealed a bench, a chair, and a mass of electronic equipment within.

'I was off duty,' he said. 'I did not give those orders.'

He spoke in Italian, but slowly, for my sake. As men, we got on very well. As linguists, speaking a little of each other's language but understanding more, we had to take time. We spoke to each other carefully, each in our own tongue, and listened with attention, asking for repetition whenever necessary.

He was the carabinieri officer who had been leading the official investigations. He had agreed throughout on the need for extreme care and for the minimum of visible involvement. No emblazoned cars with busily flashing lights had driven to or from the Villa Francese, where Paola Cenci waited with white face for news of his daughter. No uniformed men had been in evidence in any place where hostile eyes could watch. Not while Pucinelli himself had been able to prevent it.

He had agreed with me that the first priority was the girl's safety, and only the second priority the catching of the kidnappers. Not every policeman by any means saw things that way round, the hunting instincts of law enforcers everywhere being satisfied solely by the capture of their prey.

Pucinelli's colleague-on-duty on that devastating evening, suddenly learning that he could pounce with fair ease on the kidnappers at the moment they picked up the ransom, had seen no reason to hold back. Into the pregnant summer darkness, into the carefully negotiated, patiently damped-down moment of maximum quiet, he had sent a burst of men with batons waving, lights blazing, guns rising ominously against the night sky, voices shouting, cars racing, sirens wailing, uniforms running all the moral aggression of a righteous army in full pursuit.

From the dark stationary ambulance a long way down the street I had watched it happen with sick disbelief and impotent fury. My driver, cursing steadily, had started the engine and crawled forward towards the melee, and we had both quite clearly heard the shots.

'It is regretted,' Pucinelli said with formality, watching me.

I could bet it was. There had been so many carabinieri on the move in the poorly-lit back street that, unsure where to look precisely, they had missed their target altogether. Two dark-clad men, carrying the suitcase which contained the equivalent of six hundred and fifty thousand pounds, had succeeded in reaching a hidden car, in starting it and driving off before the lawmen noticed; and certainly their attention had been more clearly focused, as was my own, on the sight of the young man spilling head-first from the car which all along had been plainly in everyone's view, the car in which the ransom had been carried to this blown-open rendezvous.

The young man, son of a lawyer, had been shot. I could see the crimson flash on his shirt and the weak flutter of his hand, and I thought of him, alert and confident, as we'd talked before he set off. Yes, he'd said, he understood the risk, and yes, he would follow their instructions absolutely, and yes, he would keep me informed by radio direct from the car to the ambulance. Together we had activated the tiny transmitter sewn into the handle of the suitcase containing the ransom money and had checked that it was working properly as a homer, sending messages back to the radar in the ambulance.

Inside the ambulance that same radar tracker was showing unmistakably that the suitcase was on the move and going rapidly away. I would without doubt have let the kidnappers escape, because that was safest for Alessia, but one of the carabinieri, passing and catching sight of the blip, ran urgently towards the bull-like man who with blowing whistle appeared to be chiefly in charge, shouting to him above the clamour and pointing a stabbing finger towards the van.

With wild and fearful doubt the officer looked agonisedly around him and then shambled towards me at a run. With his big head through the window of the cab he stared mutely at the radar screen, where he read the bad news unerringly with a pallid outbreak of sweat.

'Follow,' he said hoarsely to my driver, and brushed away my attempt at telling him in Italian why he should do no such thing.

The driver shrugged resignedly and we were on our way with a jerk, accompanied, it seemed to me, by a veritable posse of wailing cars screaming through the empty streets of the industrial quarter, the factory workers long ago gone home.

'Since midnight,' Pucinelli said, 'I am on duty. I am again in charge.'

I looked at him bleakly. The ambulance stood now in a wider street, its engine stilled, the tracker showing a steady trace, locating the suitcase inside a modern lower-income block of flats. In front of the building, at an angle to the kerb, stood a nondescript black car, its overheated engine slowly cooling. Around it, like a haphazard barrier, the police cars were parked at random angles, their doors open, headlights blazing, occupants in their fawn uniforms ducking into cover with ready pistols.

'As you see, the kidnappers are in the front apartment on the third floor,' Pucinelli said. "They say they have taken hostage the people who live there and will kill them, and also they say Alessia Cenci will surely die, if we do not give them safe passage.'

Next page