Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Donna,

Liz and Eric

In 1982, shortly after Id moved to Washington, DC, I went to visit the Library of Congresss Jefferson Building, one of the citys most gorgeous landmarks, which contains, it is said, the greatest collection of knowledge in the world. The LOC had just recently converted its famed collection cataloging system (the one J. Edgar Hoover had learned during his brief stint there as a clerk early in his career) into a searchable, computerized database, something that was quite novel and innovative at the time. Out of curiosity, I went to the keyboard and typed in my last name. A simple Google search today would now reveal hundreds of hits, but back then, in the early days of the digital revolution, the LOCs computer index turned up only one: Charles Urschel, kidnapping victim. And there was one book in which he was noted prominently. It was E. E. Kirkpatricks firsthand account, Crimes Paradise: The Authentic Inside Story of the Urschel Kidnapping published in 1934. I immediately requested the book, and when the librarian pulled it from the stacks, I sat in the LOCs stately reading room and read it cover to cover. (Only members of Congress and staff can actually check a book out of the LOC.)

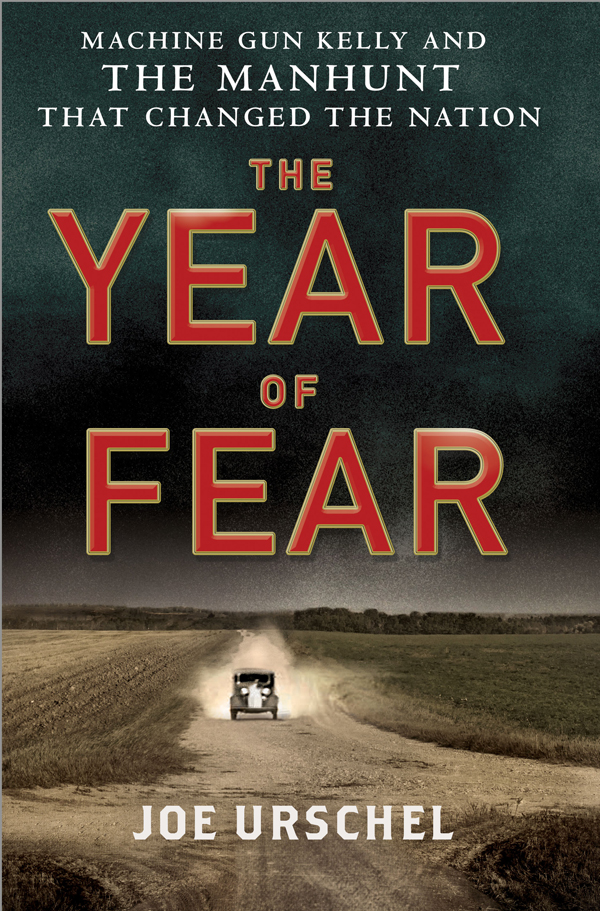

I was, of course, transfixed by Kirkpatricks rendering of a story that could have been the blueprint for a Dashiell Hammett novel. But I was also bewildered that Iand most other Americanshad never heard of the main character. This was especially embarrassing for me in that I shared his rather uncommon last name, and Id believed all the Urschels in the United States were related. Everyone seemed familiar with the name of Urschels kidnapper, the notorious George Machine Gun Kelly even if they knew nothing about his biggest crime.

My research ultimately found no American familial connection with Charles Urschel. Our relationship dates back centuries to Germany. My interest in his story, however, continued to grow as the years passed and the historical exploration into the crime wave of the 30s shed more and more light on the period and the fascinating men and women who made it so infamous.

The year of the crime, 1933, saw an extraordinary confluence of events in the country. With unprecedented dust storms inflicting further misery on a population mired in the Great Depression, Franklin Delano Roosevelt swept into office warily eyeing the almost simultaneous election of Adolf Hitler in Germany while telling his fellow Americans they had nothing to fear, but fear itself. And while he was constructing a big, activist federal government to address the nations ills, another national industry was being launched to celebrate it. With national radio news networks starting up and wire services and huge regional daily newspapers growing, the mass media as we know it today were bringing the sprawling, unwieldy country together in ways it had not experienced earlier.

The Urschel kidnapping provided a captivating scenario that dominated the headlines and airwaves from New York City to San Francisco. There were those, like Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover, who quickly learned how to use and exploit this pervasive new national megaphone to their own great benefit.

There were others, like Charles Urschel, who shunned and reviled it. Nevertheless, the decisions Urschel made, and the actions he took, had a profound effect on the course of history, just like the other, more famous and infamous men of his time. Had he not chosen the course of action he didstanding up to the threats of his captors and cooperating with the federal authoritiesJ. Edgar Hoover would have been denied the spectacular trial on which he launched his career, and George Kelly most likely would have remained in anonymity as a relative bit player in the saga of Americas gangland.

But that is not the way it happened. It happened like this

As J. Edgar Hoover lay asleep in his home in the early morning hours of July 22, 1933, he was fitfully aware of the tentative hold he had on the job he had come to know and love. He was Director of the United States Department of Justices Bureau of Investigation. At age thirty-six, he was thought by most to be too young, too inexperienced and too politically unconnected for the job most people in government considered to be barely more than a political patronage appointment. And, lately, hed been proving them right.

His teams investigation of the Charles Lindbergh baby kidnapping had been a laughable failure. The case had dragged on with no resolution or notable progress in the sixteen months since then-President Herbert Hoover had tapped him to lead the federal efforts to solve the case and find the kidnappers. His initial efforts to get involved in the investigation had been rebuffed by the New Jersey State Police, who flat out refused to share information, and dismissed his men as inept federal glory hunters. Lindbergh himself was barely cooperative.

His overreaching in the capture and arrest of an escaped federal prisoner had resulted in the mass murder of four law enforcement officers, including one from his bureau, and the prisoner himself. The machine gun assault had taken place in the parking lot of Kansas Citys busy Union Station in full view of the train stations bustling crowds.

Not only was his competence being called into question by the national press, but his masculinity was, as well. The new presidents wife was said to loathe him, and hed just barely escaped a sacking by Franklin Delano Roosevelts first choice for attorney general.

But Hoover was about to receive a phone call that would turn his fortunes around. The call would deliver to Hoover the most effective and cooperative witness in the history of the agencys war against crime. It would set into motion the biggest manhunt in the nations history and lead to a spectacular trial that would transfix the country and transform the Bureau.

The events would unleash a cavalcade of publicity that would ultimately put the beleaguered director on course to become not only the most powerful lawman in the nations history, but the most admired, as well. Within ninety days, Hoover would go from a man whose head had been on the political chopping block, to the star performer of the new administrations ambitious plans.

Hoover could not have realized all of this as his bedside telephone rang on that Sunday at 2:00 a.m. But his life was about to change, and history was about to be made.

Just weeks earlier, Hoover had established the countrys first national crime hotline, a special telephone number that anyone could call to be put through immediately to the Justice Department headquarters in Washington, DC. It was intended to be used for reporting kidnappings, a heinous crime that was occurring with alarming regularity throughout the country. Hoover hoped his hotline would tip his agents off quickly so they could get on the scene without delay and get control of the investigation before the local authorities could lock things up and freeze them out. So eager was he to get news quickly that he instructed the telephone operators at the Bureau to put calls through to a special line he had installed in his home.