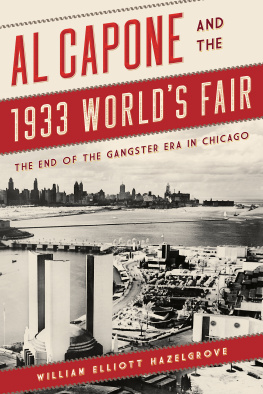

Al Capone and the 1933 Worlds Fair

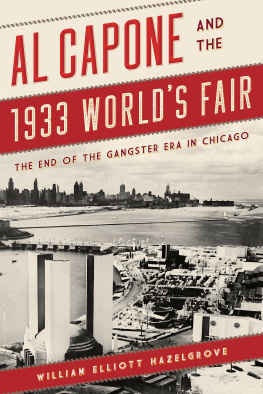

Aerial view of the 1933 Worlds Fair ( Source: Library of Congress)

Al Capone and the 1933 Worlds Fair

The End of the Gangster Era in Chicago

William Elliott Hazelgrove

Rowman & Littlefield

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2017 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hazelgrove, William Elliott, 1959 author.

Title: Al Capone and the 1933 Worlds Fair : the end of the gangster era in Chicago / William Elliott Hazelgrove.

Description: Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017006093 (print) | LCCN 2017023717 (ebook) | ISBN 9781442272279 (electronic) | ISBN 9781442272262 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Chicago (Ill.)History20th century. | Chicago (Ill.)Civilization20th century. | Chicago (Ill.)Social conditions20th century. | Century of Progress International Exposition (19331934 : Chicago, Ill.)

Classification: LCC F548.5 (ebook) | LCC F548.5 .H39 2017 (print) | DDC 977.3/11dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017006093

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

For Kitty, Clay, Callie, and Careen

A smile can get you far, but a smile with a gun can get you further.

Al Capone

I havent been out of work since the day I took off my pants.

Sally Rand

Forty Years Later

Forty years after the Columbian Exposition and Dr. H. H. Holmess macabre, psychopathic murders in 1893, Chicago decided it was time to have another worlds fair. The times and the reasons differed, though. Orville and Wilber Wright had left the earth for twelve seconds in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in 1903. The Titanic had met black ice in the Atlantic and already been resting on the bottom of the ocean for two decades. The beau arts tradition of 1893 had been left in the dust for a modernist vision of the world promoted by industry, architecture, and advertising.

The intervening years had rendered Holmess crimes quaint by comparison with the mechanized slaughter of World War I and gangsters duking it out over the fruits of Prohibition in the streets of Chicago. Humanism was dead. Technology and materialism had taken its placea very different God indeed. The secular world was using Thompson submachine guns and offering sex through peep holes and in back rooms. The 1933 Worlds Fair would hold its breath and hope Al Capone didnt pull the whole thing under.

When the Great Depression came crashing down, many thought people would never spend money on a fair in the bleakest times America had ever known. In 1933, when the fair opened, 15 million people were unemployed, and one-third of the banks had failed. Men from the J. P. Morgan and DuPont empires had plans to overthrow the government and replace Franklin D. Roosevelt with a fascist government modeled on that of Italy. Only when General Smedley Butler revealed the plans to Congress was the coup thwarted.

While the Columbian Exposition of 1893 showed that Chicago had arrived, the 1933 Worlds Fair declared that the city and the nation would survive. But a party had been going on. Bathtub gin and speculation and Americas insatiable appetite for modern conveniences and getting rich quick had fueled the 1920s. F. Scott Fitzgerald christened it the jazz age and said the gaudiest spending spree in history was beginning. Fitzgerald was right. Sleek wooden rumrunners bumped off the shores of Lake Michigan with men bringing in the booze that made its way to the speakeasies on every corner of the city of Chicago. People simply wanted to drink, and Alfonse Capone was there to make sure they could.

For a price.

That price was murder and an ongoing war between the Italian from Brooklyn and anyone who challenged his rule. Men in long coats carrying machine guns rode crouched down on the running boards of black Cadillacs and held the city in their grip. The whole country watched in fascination as gangland culture appeared in movies, fashion, and common slang while gun-toting men habitually wiped each other out with .45 Automatic Colt Pistol slugs.

The mayor of Chicago, William Thompson, owed his election to Al Capone and men who threw grenades at opposing polling stations. Another mayor, Anton Cermak, tried to clean up Chicago until an assassin supposedly hired by Capone shot him dead. The government had erred badly in legislating American morality, and Al Capone had moved in to fill the resulting demand with murder on a scale that would have shaken even a psychopath like Dr. Holmes.

In 1933, Adolf Hitler had just become chancellor of Germany, and Benito Mussolini had risen to power in Italy. The hubris of holding a worlds fair during these times seemed to invite disaster. President Roosevelt had just told the country it had nothing to fear but fear itself; then he passed the Banking Act of 1933, essentially closing banks to stop people from withdrawing their money. Charles Lindberghs baby had been kidnapped and murdered just the year before. But Chicago saw the 1933 Worlds Fair as a way to rehabilitate its sagging reputation as a Wild West town of gangsters and also as a catalyst for economic recovery. If the city could pull off A Century of Progress , then maybe it could get rid of Al Capone and the awful darkness of the Great Depression. This was the thinking after the worst gangland shooting in American history, ironically named for a holiday of love.

When people left the fair, they wondered why Chicago was so dingy compared to the shimmering metropolis on the lake. Coal burners that dropped soot down from on high still fired the city. The Union Stockyards slaughtered over a million hogs a year, with the smell wafting into Chicago when the wind blew from the south. Steam locomotives still lumbered into the city and killed pedestrians. The trains had yet to be confined to Union Station, and the soot from their coal-burning engines contributed to the brown dense fog that sometimes enveloped the city.

Many buildings manufactured their own electricity in boiler-fired dynamos tucked away below ground. The Chicago River had been reversed, but in bad storms it spewed sewage into Lake Michigan. A book published to promote the 1933 Worlds Fair gives a snapshot of the best statistics the organizers could offer up: 3.475 million people lived in Chicago in some 400,000 dwellings; they drove 396,533 automobiles along 226 miles of parklike boulevards; they attended 1,800 churches and sent their children to 360 public schools.

Only 11 percent of the population owned a car in 1933. Horses delivered milk, blacksmiths dotted city blocks, and carriages competed for space. Few people had flown in a plane. Yet the city had come a long way: from a dot on a map drawn by Antoine Charles Louis Lasalle, it had become an Indian trail, a trading post, a US government agency, and then a sprawling town of log cabins. When the Illinois and Michigan Canal opened in 1848, Chicago began to grow quickly, and three years later the village of Chicago became the city of Chicago. A reason for a worlds fair nearly a hundred years later was born.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.