ALSO BY JONATHAN EIG

Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinsons First Season

Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig

Get Capone

The Secret Plot That Captured

Americas Most Wanted Gangster

JONATHAN EIG

Simon & Schuster

New York London Toronto Sydney

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2010 by Jonathan Eig

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or

portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address

Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition April 2010

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks

of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at

1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors

to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at

1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Jill Putorti

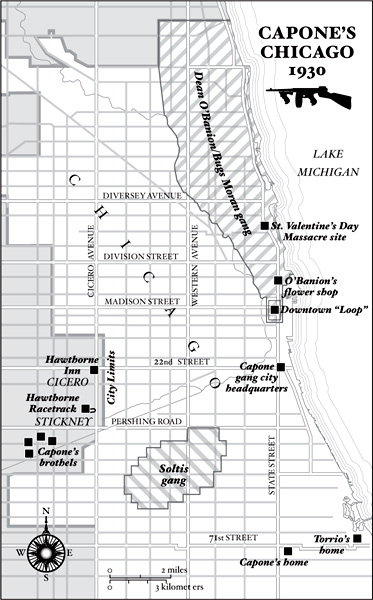

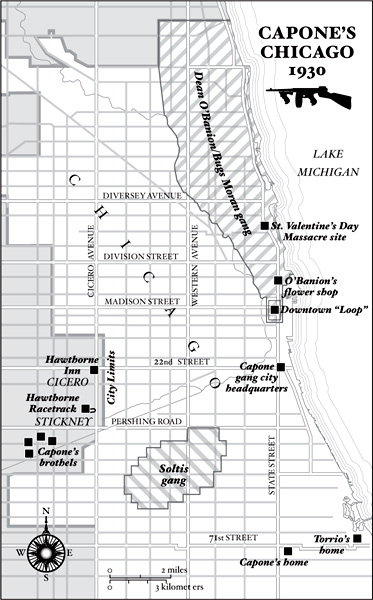

Map by Paul J. Pugliese

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2009033949

ISBN 978-1-4165-8059-1

eISBN-13: 978-1-4391-9989-3

For Lillian

CONTENTS

PART ONE

CAPONE RISING

1

THE GETTING OF IT

Al Capone stood on the sidewalk in front of a run-down saloon called the Four Deuces, the wind whipping at his face. He shoved his and pulled his jacket collar high to protect against the cold, or maybe to cover the scars on his left cheek.

, he said.

Capone was twenty-one years old and new in town. He worked in Chicagos Levee District, south of downtown, a neighborhood of sleazy bars and bordellos, where a man, if he cared about his health, tried not to stay long and tried not to touch anything. Automobiles with bug-eyed headlamps rumbled up and down the block. It was January 1920, the dawn of a rip-roaring decade, not that youd know it from looking around this neighborhood.

The Great War was over. Men were back home, maybe a little shell-shocked, maybe a little bored, certainly thirsty. They put on jackets and ties and snap-brimmed hats and went to places such as the Four Deuces, which was named not for the winning poker hand but for its address: 2222 South Wabash. It was a four-story, brick, turn-of-the-century building with a massive arched door that looked like the mouth of a cave. Inside, cigarette and cigar smoke clung to the ceiling. Some customers came for the drinks. Others climbed the stairwell at the back and went upstairs, where the smoke faded slightly but the aromas became more complex. There, on the second floor, high-heeled women paraded in varying states of undress, their movements on the ceiling. A madam urged the customers to hurry up and choose.

When the place got busy, Capone would head inside to warm himself and . He charmed people with his broad smile.

Capone cared deeply about his image. He asked photographers to capture his portrait from the right, avoiding his scarred cheek. He wore the finest clothes and, despite his girth, looked comfortable in them. It is nearly impossible to find a photograph in which he is not the best-dressed man in the room, even when he was young and poor. He had style, but he walked a fine line. He would wear suits in bright colors such as purple and lime that other hoodlums would never dare, and pinkie rings with fat, glittering stones that would put to shame many of Chicagos wealthiest society women. But he would never be seen in an ascot.

At the Four Deuces, he slid his body through the crowd with grace. He was a good host: vivacious, quick with a joke, flashing that smile. The men in the bar enjoyed his company. When he finished his shift, he would walk back to the dumpy little apartment he shared with his wife, Mae, and their one-year-old son, Albert Francis. The place wasnt much, but it was better than anything hed ever had growing up.

Capone was born and raised in Brooklyn, part of a big Italian family. His parents were immigrants. Capone grew up poor, one of nine children, and dropped out of school in sixth grade. He ran with street gangs as a boy and young man, and worked a series of menial jobs as a teenager that made good use of his size, strength, and bravado. He found his true calling as a bouncer at a dive bar on Coney Island, where he mixed with some of New Yorks toughest thugs.

He had come to Chicago to work for Johnny Torrio, once one of the legends on the Brooklyn gang scene and now a rising force in the Chicago underworld. Some accounts suggest that Torrio recruited Capone to join his organization because he spotted talent in the young man. Others suggest that Capone fled Brooklyn after a bar fight in which he nearly killed a man with his fists.

Capone took to Chicago, which the poet Carl Sandburg described this way:

Hog Butcher for the World

Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the Nations Freight Handler;

Stormy, husky, brawling,

City of the Big Shoulders:

They tell me you are wicked and I believe them,

for I have seen your painted women under the gas lamps luring farm boys.

And they tell me you are crooked and I answer:

Yes, it is true I have seen the gunman kill and go free to kill again.

Chicago city hugged the lower edge of Lake Michigan, spreading in every direction it could. In 1850, the city had been home to only . By 1870 the population had shot up to three hundred thousand. Without the watery boundaries of New York, people felt no need to jam themselves into cramped, unforgiving spaces. Neighborhoods lined up one after another along the crescent-shaped coast, wooden shanties and muddy streets stretching on into the prairie. The city grew quickly and uncontrollably. Immigrants came in search of work: building, forging steel, slaughtering cattle, loading boxcars. Criminals came, too: pimps and prostitutes, pickpockets and safecrackers, con men, dope dealers, burglars and racket men. The police departmenta mere afterthought in the citys earliest days of developmentcould never catch up.

The city burned to the ground in 1871. The Great Fire burned for days and left seventy-three miles of streets a wreck of embers and soot. Nearly a third of the citys residents were rendered homeless. But Chicago rose again, with even more speed and vigor. This time, buildings of iron, granite, and steel filled the landscape. And of course, the vice world came back stronger than ever, too. In the first eight months of 1872, the city issued an astonishing .

Next page