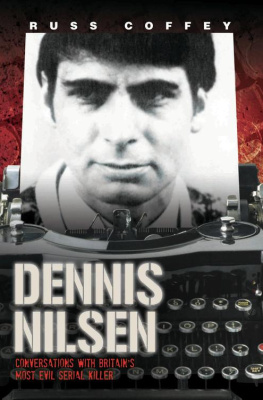

I accept moral responsibility and guilt and punishment which the law and justice demands. It has been thus since the moment of invited arrest in that top flat at 23 Cranley Gardens in that snow-driven evening in February 1983.

D ENNIS N ILSEN , I N A L ETTER T O T HE AUTHOR

O ver the years, the story of how Dennis Nilsen was arrested has been told and retold until it has acquired a ring of modern folklore. It goes like this:

On Thursday, 3 February 1983, residents of 23 Cranley Gardens, in the north London suburb of Muswell Hill, found their drains were blocked. They called a drainage engineer from Dyno-Rod. His second visit was on Wednesday, 9 February, a particularly freezing cold day. After careful thought, he concluded that pieces of flesh and bones were causing the blockage. Unsure if they were animal or human, he decided to call the police.

Three officers arrived in a squad car. After peering down the manhole, all agreed something wasnt right. They fished the pieces of grey matter out from beneath the manhole cover and took them to the lab. An hour later, the pathologist confirmed them as human. In the mortuary, the detectives knew they were dealing with something hugely significant and particularly grim.

They returned to Cranley Gardens. An inspection of the outside of the building seemed to indicate that the flesh had come from a pipe that led to the top flat. The neighbours told them that the man who lived there was peculiar and that he should be back from work in about an hour. DCI Peter Jay said they would wait. Rubbing their hands to keep warm, the three men discussed what they knew about Nilsen his name, age, and that he worried his neighbours. Still, they had little idea of what he might be like. How might a man who had possibly been chopping up bodies and flushing them down the toilet react to arrest?

Nilsen was also waiting. He had spent the afternoon at work mentally preparing himself for his arrest. Since leaving for work that morning, he been quite convinced the game was up. He knew the body parts hed been flushing down the toilet were still blocking the plumbing.

When Nilsen finally returned to his flat, the police had moved into the warmth of the lobby. Nilsen opened the door to find DCI Jay staring at him. He knowingly returned his gaze. Jay began by asking about the plumbing.

In his calm Scottish voice, Nilsen replied, Since when were the police interested in peoples drains?

The policemen suggested they take the conversation upstairs. In the flat, Jay explained about the human remains.

How awful! exclaimed Nilsen.

Jay nervously snapped, Stop messing around wheres the rest of the body?

Then, in a matter-of-fact way, Nilsen took them to the damp, cold front room and opened one of the wardrobes where he had stored bodies. He said he had much more to tell and wanted to do it at the station.

In the car back to Hornsey Police Station, the detectives asked their prisoner what it was he wanted to tell them. Had he killed two men?

Fifteen or sixteen over four years, was Nilsens reply. That made him the most prolific multiple killer yet discovered in the UK. And just like in the movies, he was quiet, intelligent and personable. His writing still often is.

In his version of those events above, however, Nilsen changes the emphasis so that it is he at the centre, looking for help. He says the police were unsure of themselves. It was he, he says, who finally tired of concealing his problem and who led the police each step of the way with his sudden, immediate and full co-operation.

Either way, the stark truth was that three young men had been senselessly murdered in that particular flat. At least nine had been killed in another. As Cranley Gardens was a top-floor flat and Nilsen didnt have a car, it had become inevitable that he would soon be caught. Nilsen even says that he deliberately invited arrest by his activities. There is no evidence for that.

What the police did find plenty of evidence for was that Nilsen suffered from a severe and dangerous personality disorder. The pot on the stove had been used to boil a human head, and the odour of death hung thick throughout the flat. In the wardrobe were bin bags filled with the remains of a Scottish youth called Steven Sinclair. Nilsen had killed him two weeks earlier, and now he wanted to explain everything.

The way he did so was distinctive. He talked almost as if he had been in love with Sinclair. In one notebook, Nilsen wrote, I stood in great grief and a wave of utter sadness as if someone very dear to me had just died.

The line was written next to an ink drawing of the corpse called The Last Time I Saw Stephen Sinclair. The juxtaposition seemed quite mad. The affection he claimed to have felt for the young man was matched with a vile disregard for his body. The torso had been cut down the middle and was separated into two halves. The lower part of the body had been removed with a clean cut from just above the waist. The eyes had been boiled in their sockets. When the pieces were re-assembled on the mortuary slab, they had turned different colours.

Stephen Sinclair was typical of those Nilsen would bring home. He was the sort whose story interests no one, and the kind of young man that Nilsen felt he could take under his wing. Sinclair was 20 years old and only 5ft-5in tall. He had come down from Scotland, travelling without a ticket on the InterCity Express from Edinburgh to Londons Kings Cross. Like many of the runaways who arrived at that station, he had come with little more than a vague feeling that the big city had something for everyone, even him.

Sinclair met his killer on Wednesday, 26 January. Nilsen isnt sure exactly where. In one version, it was in a pub called the Royal George in Goslett Yard near Denmark Street where he had once worked. One witness, however, thought he saw Sinclair hanging around with someone fitting Nilsens description some days before. So, despite what he says, Nilsen, did, quite possibly, mark Sinclair out as a potential victim beforehand.

Another, more likely, account has them meeting by the slot machines off Piccadilly Circus. This was then a well-known gay cruising area where older men would try to pick up rent boys or runaways looking for money. Dressed in a leather jacket, tight black jeans and with tattoos on his hands and arms, Sinclair would have hardly stood out. As a well-spoken man in his late thirties, neither would Nilsen.

Nilsen was 6ft 1in, slim, dark-haired and good-looking despite his oversized glasses and functional suit. We know from victims who escaped, that his manner when picking people up was usually friendly but dominating. The conversation between him and Sinclair was therefore probably one-sided, with their shared knowledge of eastern Scotland helping it along. As they chatted, Nilsen would have appeared sympathetic and kind, and would have spoken with complete confidence as if he knew everything about everything. He found Sinclair attractive, especially approving of the fact that he was small and fair two of his physical preferences. Nilsen cared less for the fact that he was a delinquent and a drug addict.

Sinclair would have seemed like a safe bet. Not only was he a runaway but he had also just been in trouble. He had been being caught stealing at a St Mungos hostel and bailed to appear before magistrates on Monday, 12 February. It was hardly the first time Sinclair had got himself into bother. In fact, hed rarely been out of trouble since he was born Stephen Guild in 1962.

He was illegitimate and was soon taken into the custody of the local authorities. After 14 months he was put up for foster care, and came into the home of Neil and Elizabeth Sinclair who adopted him to be a brother to their three daughters. Stephen Sinclair, however, wet his bed and constantly bunked off school. Things became so bad that a doctors advice was sought. It transpired that he had psycho-motor epilepsy.