Perhaps the most auspicious aspect of the birth twenty-nine minutes after midnight, Central War Time, March 17, 1942, was the date itself. It was St. Patrick's Day, traditionally one of the most widely celebrated ethnic holidays in Chicago.

The thoughts of Chicagoans and of all Americans on that day were on other things, however. Barely three months earlier the nation had been plunged into a savage and destructive world war, and American soldiers were dying in an unremitting series of demoralizing defeats in the Pacific.

Yet, at Edgewater Hospital in the city's far north side, thoughts were on life, not death and defeat. It made no difference that the parents of the St. Patrick's Day baby traced their heritage not to Ireland, but to Poland and Denmark. And it made no difference that the baby was born into a tempestuous time and into a city more known for the violent and venal ways of its citizens than for its positive accomplishments.

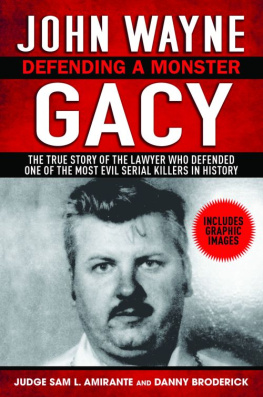

Chicago and the world welcomed the lusty, squalling baby boy. His parents named him John Wayne Gacy, Jr.

Beginning with its earliest days as a settlement, the history of Chicago has been solidly engraved with violence. Chicago has spawned and sheltered some of the country's most unscrupulous and rapacious politicians and most infamous and ferocious killers.

As the gateway to the West, Chicago had always offered fortunes to be made by those who were strong enough and bold enough to take them. Every kind of vice and corrupt scam that man could think of existed in Chicago. Even the great fire that roared through the city in 1871 failed to cleanse or slow the villainy. From the Haymarket Riot in 1886, to the St. Valentine's Day Massacre in 1929, through the Democratic Convention riots in 1968, Chicago has been identified with acts of violence.

"Chicago is unique," once observed Professor Charles E. Merriam, University of Chicago political scientist and civic reformer. "It is the only completely corrupt city in America."

But Chicagoans refuse to live in grief and loss for the past any more than they are willing to live in terror of the future. Some citizens, in fact, take a rather perverse pride in their city's violent and shifty reputation. There is never a February 14 when the media fails to commemorate the St. Valentine's Day Massacre with nostalgic stories of the mad days of Prohibition.

The Chicago Convention and Tourism Bureau would undoubtedly prefer that the city achieve its fame for landmarks like Navy Pier, the 1,468-foot Sears Tower, and Buckingham Fountain, or for such aspects of human achievement as its part in splitting the atom and opening the atomic age, or for the great men and women who lived and worked there, such as Clarence Darrow, Jane Addams, George Ade, and Richard J. Daley.

Unfortunately, too many events in Chicago history that should have been remembered with pride and satisfaction have been marred by violence. Events like the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893-94 commemorating Christopher Columbus' landing in the New World. While 21 million people were paying admission to the World's Fair along the lakefront, a little man with the prosaic name of Herman W. Mudgett was filling a charnel house on the south side with the bodies of murder victims and laying claim to the very unprosaic title of most industrious mass murderer in the history of the United States.

Mudgett, who used various aliases but preferred the name of Harry Howard Holmes or H. H. Holmes, was believed responsible for the murders of as many as two hundred victims, a large number of them unsophisticated young women and small children. Although he was linked to murders occurring as far away from his home base in Chicago as Toronto, and was eventually hanged for slaying a business partner and coconspirator in an insurance-fraud scheme in Philadelphia, investigators believed that he found many of his victims at the Columbian Exposition.

Although Mudgett eventually admitted to only twenty-seven murders and was officially credited with twelve, workmen and investigators who dug up the cellar under his murder castle found so many bones, teeth, and other fragmentary remains that it was estimated that he had killed hundreds.

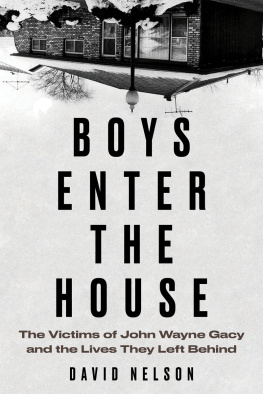

There have been other celebrated crimes in Chicago since the days of Mudgett's horror castle. Child slayings like the ruthless thrill killing of fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks in 1924; six-year-old Suzanne Degnan, whose dismembered body was pulled from sewers in 1946; the triple murder of John and Anton Schussler, thirteen- and eleven-year-old brothers, and their fourteen-year-old friend Robert Peterson in 1955; and the puzzling deaths of the Grimes sisters, fifteen-year-old Barbara and thirteen-year-old Patricia, in 1956.

The child killings were dreadful, but it was 1966 before a mass murder occurred within walking distance of the Lake Michigan beachfront near the South Chicago Community Hospital that was so sudden and savage that it horrified people throughout the world. Mudgett's grisly deeds had been exposed nearly three quarters of a century before. The torture castle had been demolished and long since forgotten. Chicago was ready for a new horror.

It was just after 6 A.M. on a warm, humid July Thursday when Patrolman Daniel R. Kelly braked his squad car to a stop outside a building in the 2300 block of East 100th Street. A young woman he later learned was twenty-three-year-old Filipino nursing trainee Corazon Amurao, was standing on a ledge ten feet above the sidewalk screaming: "Help me. Help me. They're all dead. I'm the last one alive."

Drawing his Smith & Wesson .38, Kelly clattered up a half dozen steps and through an open rear door, moving quickly past the kitchen and into the living room. He stopped abruptly. The naked body of a young woman was lying face down on a divan. By a bizarre twist of fate, he recognized the victim as Gloria Jean Davy, a pretty twenty-three-year-old nursing student he had dated. A strip of torn linen that had been used to strangle her was still stretched around her neck.

It is not unusual for a policeman to date or marry a nurse. Their jobs bring them in frequent contact. And city policemen learn to find their way around hospital emergency rooms as quickly as they learn to travel with a partner.

Kelly's partner was Patrolman Lennie Ponne. As Ponne coaxed the shrieking young woman from the ledge back into the building, Kelly moved past the body on the divan and climbed the stairs to the second floor. He was met by a hideous scene. The mutilated bodies of seven more student nurses were scattered like limp and broken dolls throughout the apartment. Their wrists were bound with linen strips. Their mouths were gagged. They were all dead.

When Miss Amurao, the lone survivor of the slaughter, had quieted enough to be questioned, she explained that she had let the killer into the building at about eleven o'clock the night before.

Six of the girls were in their rooms, she said, when someone knocked on the door downstairs. Assuming it was one of the nurses who had forgotten her key, she went downstairs and opened the door. A slender young man confronted her. He was dressed in dark trousers and a jacket that opened over a white T-shirt. He held a long, gleaming knife in one hand and a revolver in the other.

"I'm not going to hurt you. I need your money to get to New Orleans," he said, attempting to make his voice soothing and reassuring. "I'm not going to hurt you. I just want your money." The unmistakable sweet odor of whiskey followed him as she led him upstairs, the gun trained on her back.

The girls were quickly assembled in a single room and forced to lie face down on the floor as the gunman tied their hands and gagged them with strips of linen he tore from a sheet. Three other girls were professionally tied with good strong square knots and gagged as they returned to the house during the next forty-five minutes.