WEIMAR CINEMA

FILM AND CULTURE SERIES

EDITED BY NOAH ISENBERG

AN ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO CLASSIC FILMS OF THE ERA

WEIMAR CINEMA

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2009 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-50385-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Weimar cinema : an essential guide to classic films of the era/

edited by Noah Isenberg

p. cm. (Film and culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-13054-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-13055-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-50385-3 (ebook)

1. Motion picturesGermanyHistory. 2. Silent filmsGermany History and criticism. I. Isenberg, Noah William.

PN 1993.5. G 4 W 357 2008

791.430943 '09042 DC 22

2008029682

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

DESIGN BY VIN DANG

1. Suggestion, Hypnosis, and Crime:

Robert Wienes The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

STEFAN ANDRIOPOULOS

2. Of Monsters and Magicians:

Paul Wegeners The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920)

NOAH ISENBERG

3. Movies, Money, and Mystique:

Joe Mays Early Weimar Blockbuster, The Indian Tomb (1921)

CHRISTIAN ROGOWSKI

4. No End to Nosferatu (1922)

THOMAS ELSAESSER

5. Fritz Langs Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922):

Grand Enunciator of the Weimar Era

TOM GUNNING

6. Who Gets the Last Laugh?

Old Age and Generational Change in F. W. Murnaus The Last Laugh (1924)

SABINE HAKE

7. Inflation and Devaluation:

Gender, Space, and Economics in G. W. Pabsts The Joyless Street (1925)

SARA F. HALL

8. Tradition as Intellectual Montage:

F. W. Murnaus Faust (1926)

MATT ERLIN

9. Metropolis (1927):

City, Cinema, Modernity

ANTON KAES

10. Berlin, Symphony of a Great City (1927):

City, Image, Sound

NORA M. ALTER

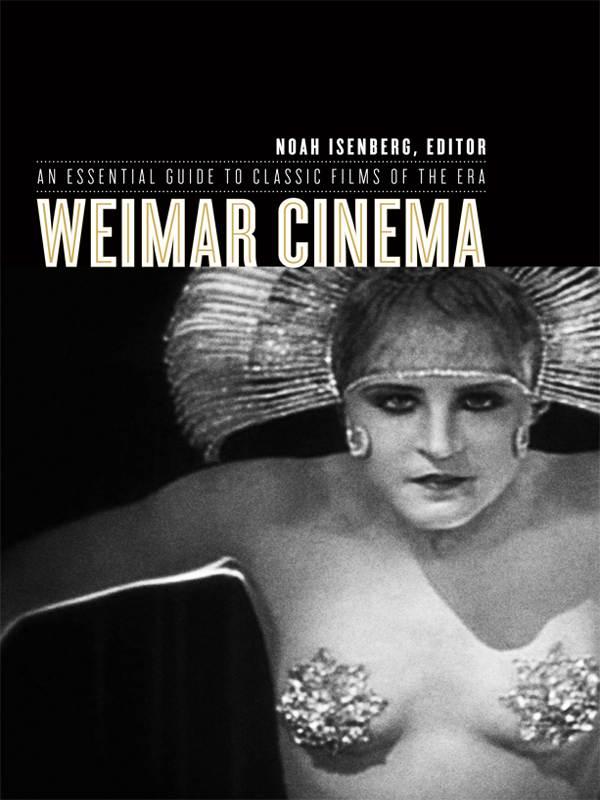

11. Surface Sheen and Charged Bodies:

Louise Brooks as Lulu in Pandoras Box (1929)

MARGARET MCCARTHY

12. The Bearable Lightness of Being:

People on Sunday (1930)

LUTZ KOEPNICK

13. National Cinemas / International Film Culture:

The Blue Angel (1930) in Multiple Language Versions

PATRICE PETRO

14. Coming Out of the Uniform:

Political and Sexual Emancipation in Leontine Sagans Mdchen in Uniform (1931)

RICHARD W. MCCORMICK

15. Fritz Langs M (1931):

An Open Case

TODD HERZOG

16. Whose Revolution?

The Subject of Kuhle Wampe (1932)

MARC SILBERMAN

A book of this kind, truly collaborative and fundamentally dependent on the critical input of others, has arguably racked up more debts of gratitude than any other project with which I have been affiliatedmore, in fact, than can be fully accounted for in this space. At the outset, a hearty thank you should be extended to the early pioneers of the field, especially to Tony Kaes, whose Weimar cinema courses (one of which I was fortunate to attend and for which I also served as a teaching assistant) have left a lasting imprint on the discipline at large and on this study in particular. The book began, several years ago, as a conversation over lunch with Film and Culture series editor John Belton and Columbia University Press editorial director Jennifer Crewe, both of whom expressed immediate support and who have maintained that support, and shown enormous patience, throughout the process. At Columbia University Press I have had the good fortune of working with Juree Sondker, who coached me through a few snags and offered astute advice at several junctures, and more recently with Afua Adusei, who has helped steer things through the thickets of production. Joe Abbott, the copy editor of the book, deserves much praise for his meticulous inspection of the entire manuscript and for his incisive queries and recommendations. I would also like to thank the three anonymous readers for their useful reports, which gave detailed and perceptive advice for revision, and the contributors themselves for their willingness to incorporate the suggestions. At the New School I would like to thank several colleagues who have offered support and encouragement at various stages of the project: Neil Gordon, Ann-Louise Shapiro and Jonathan Veitch. My student Cullen Gallagher, who helped compile the preliminary information for the volumes filmography, deserves thanks. And Melanie Rehak, who has lived with this project, and with Weimar cinema more generally, for more years than she may have bargained forand who has lent a generous hand in the volumes editorial revisionshas earned the most gratitude of all.

NOAH ISENBERG

FALLING IN LOVE AGAIN

There is a pivotal scene almost halfway into Josef von Sternbergs Der blaue Engel ( The Blue Angel , 1930) in which the still upstanding Professor Immanuel Rath (Emil Jannings), a man who epitomizes imperial Prussian rigidity teetering on the brink of collapse, finds himself drawn back to the same seedy nightclub where he first encountered the enchanting songstress Lola Lola (Marlene Dietrich). There, as the stodgy old teacher makes his way to the balcony, he finds Lola onstage, swaying her hips nonchalantly while she belts out one of her signature balladspronouncing her inability to do anything but love and finally declaring her innocence vis--vis the men who swarm around her like moths around a flame and get burned in the process. Punctuating the scene, the honorary guest Professor Rath receives a hearty welcome and a call for applause from a gruff, surly magician called Kiepert (Kurt Gerron). From his perch above the main floor, Rathand, of course, we together with himcan take in everything: the raucous, mixed crowd; the tawdry stage arrangement cluttered with scantily-clad female performers, Lola at its center; a melancholy clown, gazing up at him in ominous anticipation of an inevitable role reversal; and an oversized nude mermaid statue, whose voluptuous form catches him off guard and finally leads his attention back to the stage. As Lola strikes her seductive, by now iconic, pose atop a wooden keg (), with legs in sharp focus in a tightly framed shot and a look of complete self-assurance on her face, Rath cannot contain his delight. In the end, he is positively smitten.

The scene is significant not only for its role in the basic plot development, as it prepares Rath for his ultimate descent into shame and humiliation, but also in terms of its broader commentary on Weimar cinema as a whole. Quite self-conscious in its approach, the scene highlights the boldness of the New Woman, a stock character in Weimar cinema, at least since the so-called street films of the early 1920s, introduced here in the figure of the international star. It captures, moreover, the spirit of Weimar, or what has come to be seen as that spirit, a dance on the edge of a volcano, in the words of Peter Gay (1968, xiv), or the historical imaginary, as Thomas Elsaesser (2000) has since conceived it: the pulsating, decadent nightlife, where such slogans as Everything that pleases is allowed appear entirely credible; the powerful undercurrent of eroticism and unbridled sexuality that reached poignant expression in the visual arts, culture, and literature throughout the interwar years, threatening to subvert bourgeois morality; the paradox of love, often unrequited, in an otherwise seemingly cold, loveless society in which desire handily trumps emotion; and finally, the recurrent clashes between rival generations, classes, and political and social orientations, as well as between a heady force of internationalism and an unyielding German provincialism. Even the films music (Friedrich Hollaenders Ich bin von Kopf bis Fu auf Liebe eingestellt, or Falling in Love Again in the English rendition), coupled with rather racy narrative lyrics, strikes a resonant chord in many other films of the era, as it, too, underscores the sense of helplessness that overwhelmed those who fell into the trap that was the false promise of Weimar. It evokes the misplaced hope in the newin democracy, a cosmopolitan urban culture, and a progressive ethosthat would ultimately prove impossible to sustain beyond the confines of a short-lived experiment.