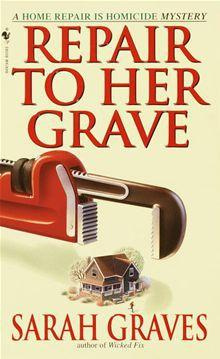

SARAH GRAVES lives with her husband in Eastport, Maine, in the 1823 Federal-style house that helped inspire her books. She is the author of six Home Repair Is Homicide mysteries The Dead Cat Bounce, Triple Witch, Wicked Fix, Repair to Her Grave, and Unhinged.

Chapter 1

H arriet Hollingsworth was the kind of person who called 911 the minute she spotted a teenager ambling down the street, since as she said there was no sense waiting for them to get up to their nasty tricks. Each week Harriet wrote to the Quoddy Tides, Eastport's local newspaper, a list of the sordid misdeeds she suspected all the rest of us of committing, and when she wasn't doing that she was at her window with binoculars, spying out more.

Snoopy, spiteful, and a suspected poisoner of neighborhood cats, Harriet was confidently believed by her neighbors to be too mean to die, until the morning one of them spotted her boot buckle glinting up out of his compost heap like the wink of an evil eye.

The boot had a sock in it but the sock had no foot in it and despite a diligent search (one wag remarking that if Harriet was buried somewhere, the grass over her grave would die in the shape of a witch on a broomstick) she remained missing.

Isn't that just like Harriet? my friend Ellie White demanded about three weeks later, squinting up into the spring sunshine.

We were outside my house in Eastport, on Moose Island, in downeast Maine. Stir up as much fuss and bother as she could, Ellie went on, but not give an ounce of satisfaction in the end.

Thinking at the time that it was the end, of course. We both did.

At the time. My house is a white clapboard 1823 Federal with three full floors plus an attic, forty-eight big old double-hung windows with forest-green wooden shutters, three chimneys (one for each pair of fireplaces), and a two-story ell.

From my perch on a ladder propped against the porch roof I looked down at Ellie, who wore a purple tank top like a vest over a yellow turtleneck with red frogs embroidered on it. Blue jeans faded to the color of cornflowers and rubber beach shoes trimmed with rubber daisies completed her outfit.

Running out on her bills, not a word to anyone, she added darkly.

In Maine, stiffing creditors is not only bad form. It's also a shortsighted way of trying to escape your money troubles, since anywhere you go in the whole state you are bound to run into your creditors cousins, hot to collect and burning to make an example out of you. That was why Ellie thought Harriet must've scarpered to Vermont or New Hampshire, leaving the boot as misdirection and her own old house already in foreclosure.

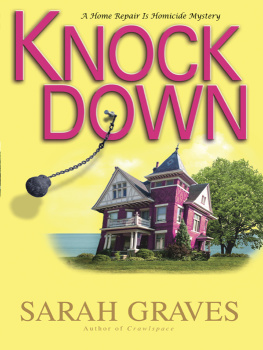

From my ladder-perch I glimpsed it peeking forlornly through the maples, two streets away: a huge Victorian shambles shedding chunks of rotted trim and peeled-off paint curls onto an unkempt lawn. Just the sight of its advancing decrepitude gave me a pang. Id started the morning optimistically, but fixing a few gutters was shaping up to be more difficult than Id expected.

Harriet, Ellie declared, was never the sharpest tool in the toolbox, and this stunt of hers just proves it.

Mmm, I said distractedly. I wish this ladder was taller.

Shakily I tried steadying myself, straining to reach a metal strap securing a gutter downspout. Over the winter the downspouts had blown loose so their upper ends aimed gaily off in nonwater-collecting directions. But the straps were still firmly fastened to the house with big aluminum roofing nails.

I couldn't fix the gutters without taking the straps off, and I couldn't get the straps off. They were out of my reach even when, balancing precariously on tiptoe, I swatted at them with the claw hammer. Meanwhile down off the coast of the Carolinas a storm sat spinning over warmer water, sucking up energy.

Ellie, run in and get me the crowbar, will you, please?

Days from now, maybe a week, the storm would make its way here, sneakily gathering steam. When it arrived it would hit hard.

Ellie let go of the ladder's legs and went into the house. This I thought indicated a truly touching degree of confidence in me, because I am the kind of person who can trip while walking on a linoleum floor. I sometimes think it would simplify life if I got up every morning, climbed a ladder, and fell off, just to get it over with.

And sure enough, right on schedule as the screen door swung shut, the ladder's feet began slipping on the spring-green grass. I should mention it was also wet grass, since in Maine we really only have three seasons: mud time, Fourth of July, and pretty good snowmobiling.

Ow, I said a moment later when Id landed hard and managed to spit out a mouthful of grass and the mud. Then I just lay there while my nervous system rebooted and ran damage checks. Arms and legs movable: okay. Not much blood: likewise reassuring. I could remember all the curse words I knew and proved it by reciting them aloud.

A robin cocked his bright eye suspiciously at me, apparently thinking Id tried muscling in on his worm-harvesting operation. I probed between my molars with my tongue, hoping the robin was incorrect, and he was, and the molars were all there, too.

So I felt better, sort of. Then Ellie came back out with the crowbar and saw me on the ground.

Jake, are you all right?

Fabulous. The downspout lay beside me. Apparently Id flailed at it with the hammer as I was falling and hooked it on my way down.

Ellie's expression changed from alarm to the beginnings of relief. I do so enjoy having a friend who doesn't panic when the going gets bumpy. Although I suspected there was liniment in my future, and definitely aspirin.

Oof, I said, getting up. My knees were skinned, and so were my elbows. My face had the numb feeling that means it will hurt later, and there was a funny little click in my shoulder that Id never heard before. But across the street two dapper old gentlemen on a stroll had paused to observe me avidly, and I feel that pride goeth before and after the fall, like parentheses.

Hi, I called, waving the hammer in weak parody of having descended so fast on purpose. The sounds emanating from my body reminded me of a band consisting of a washtub bass, soup spoons, and a kazoo.

Some were the popping noises of tendons snapping back into their proper positions. But othersthe loudest, weirdest oneswere from inside my ears.

The men moved on, no doubt muttering about the fool woman who didn't know enough to stay down off a ladder. That was how I felt about her, too, at the moment: ouch.