FRIEDRICH RECK (18841945) was born Friedrich Percyval Reck in Masuria, East Prussia, the son of a prosperous conservative politician and landowner. Having initially complied with his fathers wishes to pursue a military career, he left the army to begin medical studies. By the beginning of the First World War, for which he was ruled unfit to serve, he had begun work as a full-time theater critic and travel writer. In the following decades he became a well-known figure in Munich society, the author of both literary historical novels and popular entertainments including Bomben auf Monte Carlo (Bombs on Monte Carlo), a best-selling comic novella and the basis of a hit musical film starring Peter Lorre. In October 1944 he was arrested for the first time; in December of the same year the Gestapo returned to detain him again; in January 1945 he arrived at the Dachau concentration camp, where he was to die shortly after.

PAUL RUBENS (19272003), a self-educated native New Yorker, mastered the German language as a member of the U.S. occupation forces after World War II.

RICHARD J. EVANS is Regius Professor of History and president of Wolfson College, Cambridge. He is the author of The Third Reich at War.

DIARY OF A MAN IN DESPAIR

FRIEDRICH RECK

Translated from the German by

PAUL RUBENS

Afterword by

RICHARD J. EVANS

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1966 by Henry Goverts Verlag GmbH, Stuttgart

Translation copyright 2000 by Paul Rubens

Afterword copyright 2013 by Richard J. Evans

All rights reserved.

First published in Germany in 1947 by Burger Verlag as Tagebuch eines Verzweifelten

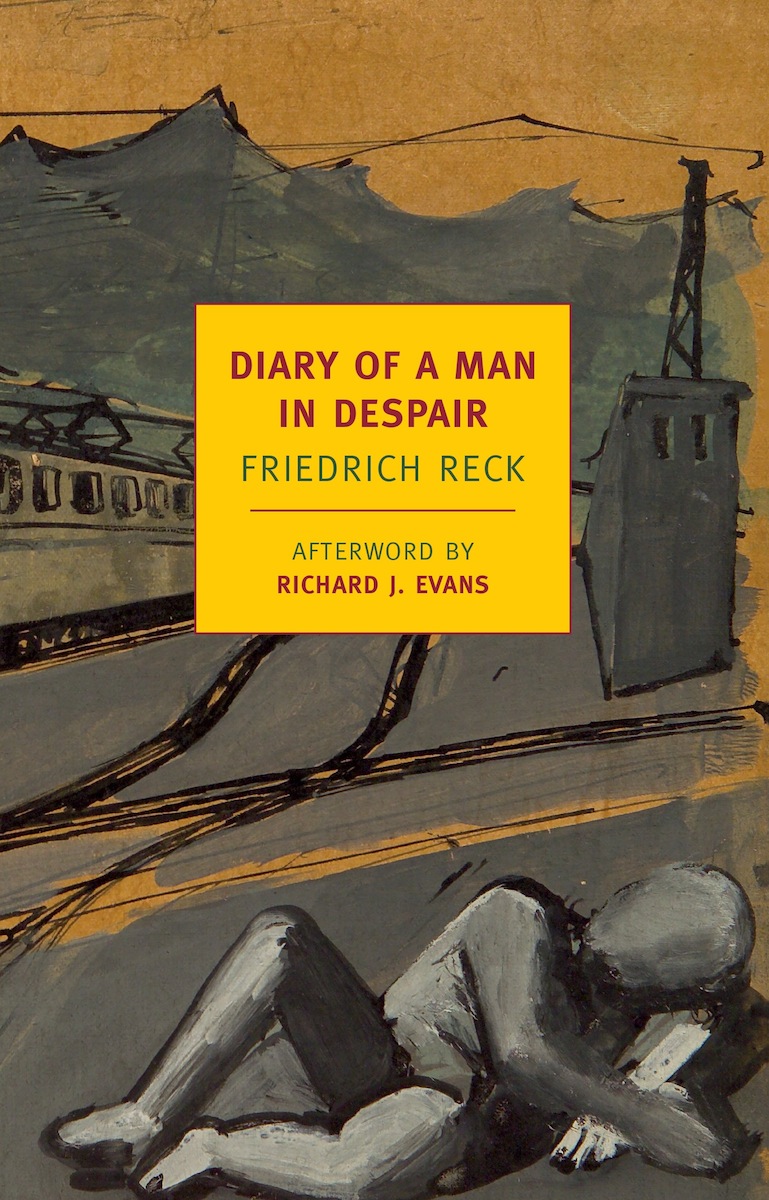

Cover image: Mario Sironi, Scalo ferroviario con manichino (detail), c. 1920; copyright 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome; digital image courtesy Associazione Mario Sironi

Cover design: Katy Homans

The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier printing as follows:

Reck-Malleczewen, Fritz Percy, 18841945.

[Tagebuch eines Verzweifelten. English]

Diary of a man in despair/by Friedrich Reck; afterword by Sir Richard Evans; translation by Paul Rubens.

pages cm.(New York Review Books classics)

Originally published: New York : Macmillan Company, 1970.

ISBN 978-1-59017-586-6 (alkaline paper)

1. Reck-Malleczewen, Fritz Percy, 18841945. 2. GermanyPolitics and government1933-1945. 3. Political corruptionGermanyHistory20th century. 4. GermanySocial conditions19331945. 5. World War, 19391945Personal narratives, German. 6. World War, 19391945Germany. 7. Authors, German20th centuryBiography. 8. Aristocracy (Social class)GermanyBiography. 9. GermanyHistory19331945Biography.

I. Title.

DD253.R384 2013

943.086092dc23

[B]

2012038369

ebook ISBN: 978-1-59017-599-6

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

DIARY OF A MAN IN DESPAIR

May 1936

Spengler is dead, then. And just as a deceased maharajah has the right to have all his retainers buried with him, this preponderant personality was, a few days later, followed in death by Albers, who had handled his work at the Beck publishing firm. Albers died in a truly grisly fashion. He threw himself under the wheels of the Starnberg train, and his bloody corpse was found on the tracks, legs severed at the thighs.[]

As for Spengler, our last meeting was just a few weeks ago on Bayerstrasse, in Munich. As usual, he had been attired in expensive tweeds. As usual, too, his brow had been dark, and his tone angry; his deep hurt and thirst for revenge on those who had hurt him emerged in a series of striking prognoses. It had been worth ones while to spend time with him.

I still remember our first meeting, when Albers brought him to my house. On the little carriage which carried him from the station, and which was hardly built with such loads in mind, sat a massive figure who appeared even more enormous by virtue of the thick overcoat he wore. Everything about him had the effect of extraordinary permanence and solidity: the deep bass voice; the tweed jacket, already, at that time, almost habitual; the appetite at dinner; and at night, the truly Cyclopean snoring, loud as a series of buzz saws, which frightened the other guests at my Chiemgau country house out of their peaceful slumbers.

This was at a time when he was not really successful, and before he had done an about-face and marched into the camp of the oligarchy of industrial magnates, a retreat which determined his life from then on. It was a time when he was still capable of being gay and unpreoccupied, and when he could sometimes even be persuaded to venture forth in all his dignity for a swim in the river. Later, of course, it was unthinkable that he expose himself in his bathing suit before ploughing peasants and farmhands, or that he climb, a huffing and puffing Triton, back onto the river bank in their presence!

He was the strangest amalgam of truly human greatness and small and large frailties that I have ever encountered. If I recall the latter now, it is part of my taking leave of him, and so I am sure it will not be held against me. He was the kind of man who likes to eat alonea melancholy-eyed feaster at a great orgy of eating. With a certain amusement, I recall one evening when he joined Albers and me for a light supper. It was during the final weeks of the First World War, when there was not a great deal one could set before ones guests. But, discoursing and declaiming the whole time, Spengler finished an entire goose without leaving us, his table companions, so much as a bite.

His passion for huge dinners (the check for which was later picked up by his industrial Maecenas) was not his only diverting attribute. After I had met him, still before his first major success, he asked me not to come to visit him at his little apartment (I believe it was on Agnesstrasse,[] in Munich). The reason he gave was that his apartment was too confined, and he wanted to show me his library in surroundings appropriate to its monumental scope.

Then, in 1926, after he had found his way to the mighty rulers of heavy industry[] and had moved to expensive Widenmayerstrasse on the banks of the Isar, he did, indeed, invite me to see the succession of huge rooms in his apartment there. He showed me his carpets and paintings, and even his bedwhich was truly worth seeing, because it looked more like a catafalquebut he became visibly disconcerted when I said that I was still looking forward to seeing the library. After overcoming his reluctance to show it to me, I found myself in a rather small room. And thereon a well-battered walnut bookstand, alongside a row of Ullstein books and detective storiesstood what are commonly called dirty books.

But I have never known a man with so little sense of humour and such sensitivity to even the smallest criticism. There was nothing he abhorred so much as humbug; yet along with all the magnificent deductions in The Decline of the West, he allowed a host of inaccuracies, inadvertencies, and actual errors to stand uncorrectedsuch as that Dostoyevsky came into the world in St Petersburg rather than in Moscow, and that Duke Bernhard of Weimar died before Wallenstein was assassinatedand important conclusions were drawn from these errors. Mistakes like these could happen to anyone; but woe to the man who dared make Spengler aware of them!