THE LURE OF THE HONEY BIRD

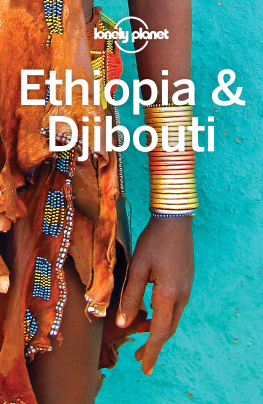

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn Ltd, West Newington House, 10 Newington Road, Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

Text and index copyright Elizabeth Laird 2013

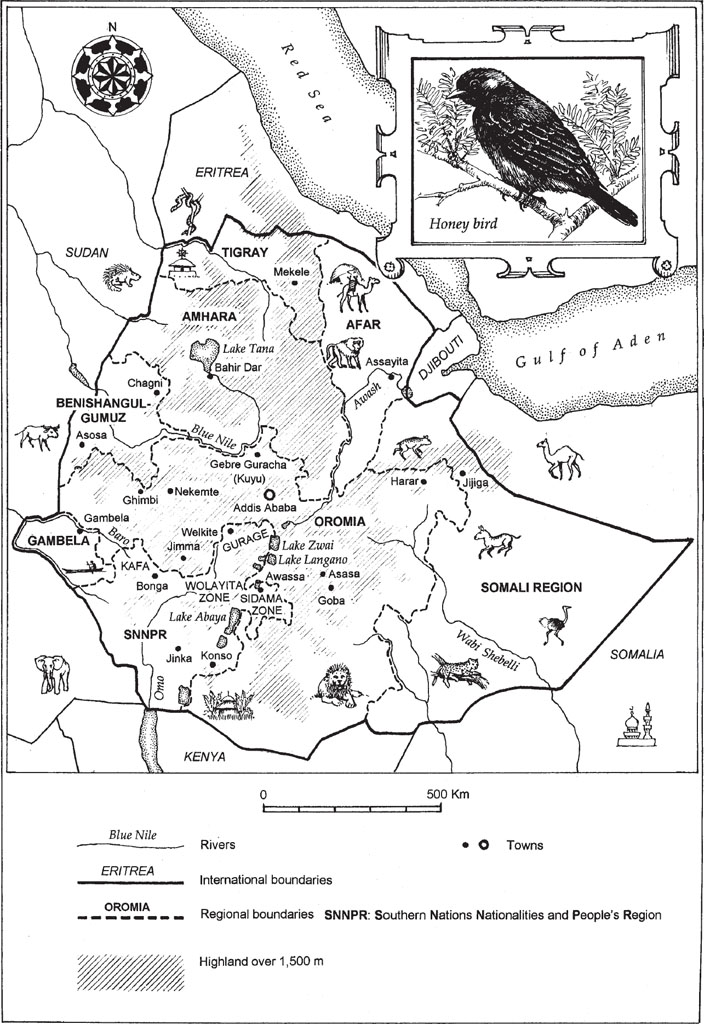

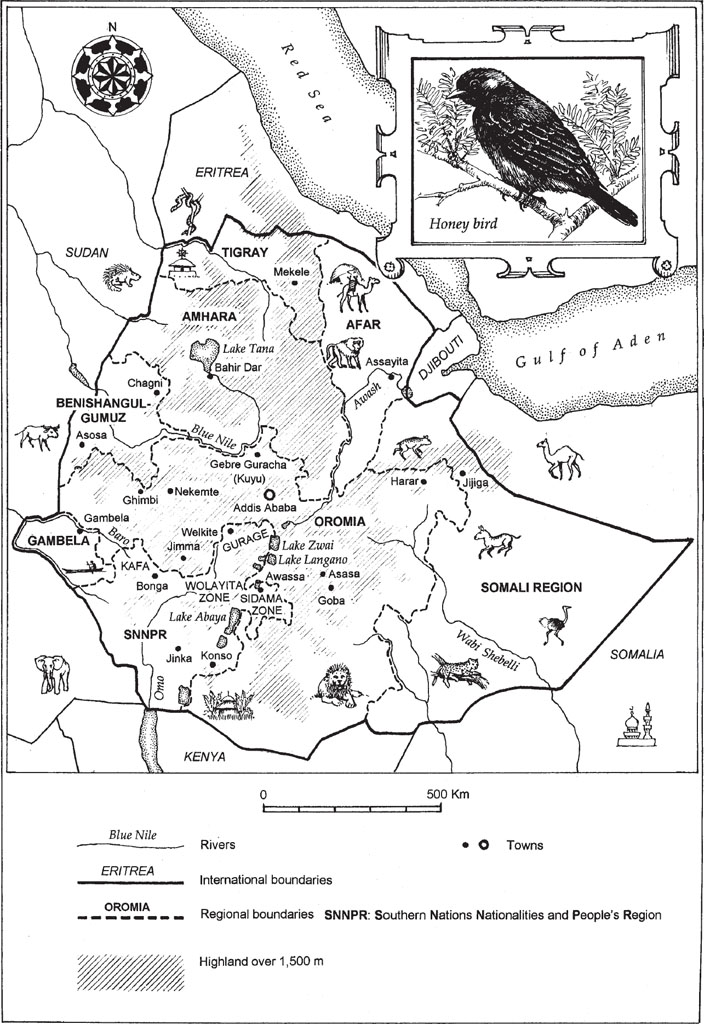

Map copyright Eric Robson 2013

Illustrations copyright Yosef Kebede and Eric Robinson (pages 228 and 254)

The right of Elizabeth Laird to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. Images have been reproduced in good faith, however, the author and publisher would be grateful if notified of any corrections.

ISBN 978 1 84697 246 1

eBook ISBN 978 0 85790 581 9

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Text design by Teresa Monachino.

For the storytellers of Ethiopia

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is a personal account of a project with many collaborators. The British Council and the Ethiopian Ministry of Education were joint partners. They organised and supported the collection of stories and the publication of the readers with generous help from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Michael Sargent, Director of the British Council in Ethiopia, was the prime mover, and with his wife Patsy a constant support and inspiration, but I must also thank Dr Simon Ingram-Hill, the late Michael Daniel Ambatchew and Dr Solomon Hailu of the British Council, as well as Dirije and Tekle, the brave and tireless drivers. The three talented and cheerful translators on the project, Michael Daniel Ambatchew, Mikhail Negussie and Mesfin Habte-Mariam, accompanied me on my journeys, put up with many difficulties, patiently resolved dilemmas and often made me laugh. At the Ministry of Education, special thanks are due to all those who showed such interest in the project and gave it essential practical support, under the guidance of the Minister of Education, Woizero Genet Zewdie.

Throughout Ethiopia, the practical arrangements for my visits, the meetings with storytellers and the organisation of translators were handled enthusiastically and with great kindness by officers of the Regional Cultural and Education Bureaux. Their names are listed below, and apologies are due to any who have been omitted.

AFAR: Mohammed Ahmed Algani and Ousman Mohammed Ahmed;

AMHARA: Alemayehu Gebrehiwot and Daniel Legesse;

BENI SHANGUL: Dires Gebremeskel and Belay Makonnen;

GAMBELA: Ogota Agiw;

HARAR: Nejaha Ahmed;

OROMIA: Merga Debelo and Bekar Hadji;

SOUTHERN REGION: Nigatu Wolde, Tiringo Segatu, Yacob

Woldemariam Dimeno, Mamo Malla and Mitachew Belay;

SOMALIA: Moge Abdi Omar;

TIGRAY: Mesele Zeleke and Tschaynesh Gebre Yohannes.

The artist Yosef Kebede worked on the reader project from the start, taking great pains with the complexity of cultural references in the different regions. A few of his illustrations have been reproduced in this book. Thanks are also due to Eric Robson for the map of Ethiopia and the illustrations on pages 228 and 254.

This book owes its very existence to Wolde Gossa Tadesse and to the generosity of the Christensen Foundation, who funded the website www.ethiopianfolktales.com in both English and Amharic, on which all the stories can be read and heard, and supported the publication of this book. Michael Sargent was a co-creator of the website, along with Gareth Cromie, who with his team designed and produced it.

My personal thanks are due to Robin and Merril Christopher, who kindly put me up in Addis Ababa, to Fiona Kenshole of Oxford University Press, to Marc Lambert of Scottish Book Trust, to Jane Fior, best of friends and encouragers, to all at Polygon, to my agent Hilary Delamere and, as ever, to my husband, David McDowall, who has supported and encouraged me throughout.

ADDIS ABABA

Addis Ababa leans against the slope of Mount Entoto like a child lying on the shoulder of its mother. I like to take the steep road up to the top of the mountains long ridge every time I visit Ethiopia. The land beneath ones feet swoops away to the south, levelling out onto a vast plain where the hot light shimmers in shifting shades of green and blue, before it rises again up the sides of Mount Wuchacha.

From this vantage point, the city below looks like a vast shanty town, intersected by the sweeps of grand avenues. This is an illusion. It is true that most houses are small, that the walls, made of mud and straw, list alarmingly when of a certain age, and that all the roofs are of corrugated iron, on which the downpours of the Big Rains clatter with a roar. But unlike a shanty town, Addis Ababa has an underlying structure, even a certain orderliness. Each district has a controlling administration, called the kebele, and although many back streets are little more than lanes, treacherous with mud in the Rains, and negotiable only by donkey hooves and human feet, they are less haphazard than they seem.

They do not, however, yield their secrets easily. There are no AZ maps of Addis Ababa, no plans or directories. To find the house of a friend you have to follow elaborate directions.

You know the Bio-Diversity Foundation?

No.

Yes, you do. Theres a sign near it saying A Twist Night Club. Turn up the lane beyond it, then the next one to the right after the Paradise Heaven Pasterie. Youll probably see a priest sitting on the corner under a striped umbrella. Our place is just beyond him.

Up on Entoto, the thin cool air is spiced with the scent of eucalyptus and the city is a hundred years and a minds journey away. Forty years ago, when I used to ride Meskel, my nervous grey pony, along the ridge of Entoto, the city was a fraction of the size it is now, the air was polluted only with the smoke of cooking fires and the sky was blue all the way down to the horizon. These days, one looks down on a smudge of pollution, and one is no longer struck by the sound of barking dogs, squealing children, saws, hammers and the clatter of small workshops, but the drone of traffic.

The temperature always catches you out in Ethiopia. The sun beats down with equatorial intensity on your bare skin. But as soon as you step into the shade, its so cool that you need a sweater. As a result, a fussy person like me is constantly fiddling with hats and over-garments.

Next page