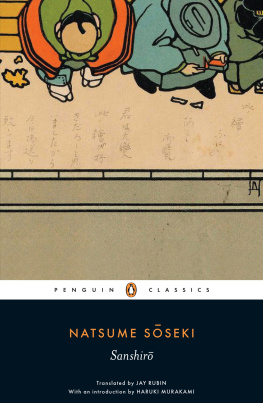

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

PENGUIN CLASSICS

BOTCHAN

NATSUME SSEKI is universally recognized to be Japans greatest modern novelist. Born Natsume Kinnosuke in Edo in 1867, the year before the city was renamed Tokyo, he survived a lonely childhood, being traded between foster and biological parents, was deeply schooled in both the Chinese classics and English, and at the age of twenty-two chose from a Chinese source the defiantly playful pen name Sseki (Garglestone) to signify his sense of his own eccentricity. In 1893, Sseki became the second graduate of (Tokyo) Imperial Universitys English Department and entered the graduate program, but in 1895 he abruptly took a position teaching English in a rural middle school. Though hoping to become a writer as early as the age of fourteen, Sseki chose the more respectable path of English literature scholar, was sent to London by the Ministry of Education in 1900 for two years, and taught in his alma mater until 1907, when his early success as a part-time writer of stories and novels led him to accept a position as staff novelist for the Asahi Shinbun newspaper, in which he serialized the rest of his fourteen novels. Sseki also published substantial works of literary theory and history (and contemplative essays, memoirs, lectures on the individual and society, etc.) and continued to think of himself as a scholar after his controversial resignation from the university. His works quickly lost any hint of academic artifice, however, relying initially on a freewheeling sense of humor, and then darkening as Sseki wrestled with increasingly debilitating bouts of depression and illness. Sseki wrote many Chinese poems and haiku as a form of escape from the stresses of the world he had created. He died in 1916 with his last and longest novel still unfinished. Each new generation of Japanese readers rediscovers Sseki, and Western readers find in him a truly original voice among those artists who have most fully grasped the human experience.

J. COHN studied Japanese at Cornell and Harvard universities, as well as in Japan, and has taught Japanese literature at Harvard University and the University of Hawaii. He is the author of a study on the comic spirit in modern Japanese fiction.

Introduction

Botchan takes its title from the nickname given to the main character, who doubles as the novels narrator, by the devoted old family maidservant Kiyo. Applied exclusively to boys and young men of respectable families, along with the occasional adult male who has not quite managed to grow up, the term can be used either as a description or as one of the many titles that are called upon to serve as a substitute for personal names in Japan. It may be used to express a measure of respect mixed with fondness for and intimacy with its subject, as Kiyo does; at other times it carries a mildly dismissive tone. It has several connotations, sometimes conceived of as interrelated and sometimes taken as independent of each other: a younger son; inexperienced or naive; easygoing in a way that can either be mildly endearing or distressingly irresponsible; or, in extreme cases, spoiled rotten. All of these, except for the last, apply to the title character to a greater or lesser degree, but there is more to him than the sum of these parts, and some of his qualities are quite the opposite of what the term might lead us to expect.

A century on from its initial publication, Botchan remains one of the most familiar, most read, and most loved of all novels in Japan. Its popularity has persisted even as the Japan it depicts, where a crash program of modernization was transforming every aspect of life but the ways of the feudal period still remained a living memory, has itself passed into the realm of distant nostalgia. It has also managed to survive its adoption as a school text, a fate that might well have proved to be a kiss of death for a less appealing book. Yet for all its obvious merits among them its tangy style, refreshingly lighthearted yet tough-minded spirit, sparkling humor, and an array of colorful characters known by memorable nicknames there is still something a little odd, a little idiosyncratic about this enduring popularity.

Artistically it is not an especially polished work: its phrasing and structure are often loose and bumpy, not surprisingly for a novel dashed off by a young professor of English who seems to have been more intent on venting his frustrations and amusing a small audience of associates than on reaching for immortality. It offers few hints of the psychological and philosophical depth that distinguish Natsume Ssekis later novels (which were soon to establish him as Japans pre-eminent modern novelist, a position from which he has never fallen), or of the exquisite suggestiveness, penetrating insights, or inventive brilliance of so many later Japanese writers. While Botchans upright, straightforward nature is occasionally cited as an embodiment of typical Japanese character, surely it is significant that Sseki portrays him and the few kindred spirits he finds as the exceptions in a society dominated by hypocrites and schemers.

This, in fact, may be a key to its popularity: if anything, what is atypical about it, the way that it differs from so many other classics, may be precisely what has continued to appeal to generations of Japanese readers even as their world has continued to change, sometimes drastically, all around them. The voice in which Botchan tells his story is striking, not quite like anything seen in Japanese fiction before, and not often matched since: sometimes choppy but always vivid, direct, and outspoken; basically colloquial but frequently enriched by literary expressions at strategic points. The reader has the sense of being in direct touch with an engaging, refreshingly candid character who may do some boasting but never talks down to us. The contrast between his forthrightness and the devious, pompous tones of many of the other characters makes him all the more appealing.

Botchans language is a superb fit for what must be the principal attraction of the novel for many readers its irreverent, accept-no-nonsense spirit. In a society, a culture, and a literature in which deference to all forms of authority is stressed and indirection is widely held to be the most appropriate mode of expressing ones thoughts and conducting ones affairs, or the only viable one, Botchans unapologetic defiance of the constraints of family life and school routines, and his willingness to expose great and petty pretensions and skulduggeries wherever he finds them, regardless of the consequences, must resonate powerfully with readers who feel the same resentments but find themselves unable to act on them or even voice them.

These themes may also resonate with English-speaking readers who have already experienced similar satisfactions while reading Huckleberry Finn or The Catcher in the Rye; and for those without direct experience of Japanese life, they may also provide an eye-opening antidote to long-prevalent media (and academic) evocations of a harmonious, largely complacent social order. The same applies to Botchans, or rather Natsume Ssekis, childs-eye view of family life, which is shockingly cold and disconnected. No doubt there is an element of intentional exaggeration for maximum emotional impact here but the same could just as easily be said of the more familiar evocation of childhood in a warm, enveloping atmosphere as celebrated in countless Japanese television series.