Published 2013 by Prometheus Books

Machiavelli: A Renaissance Life. Copyright 2013 by Joseph Markulin. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

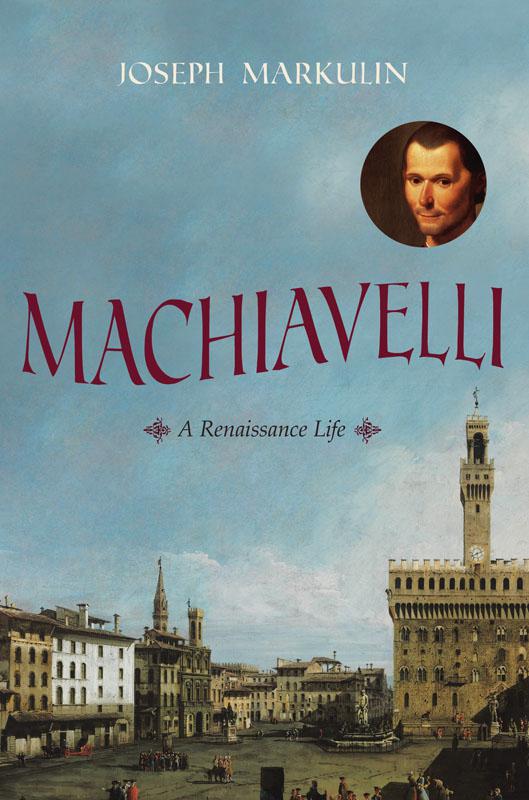

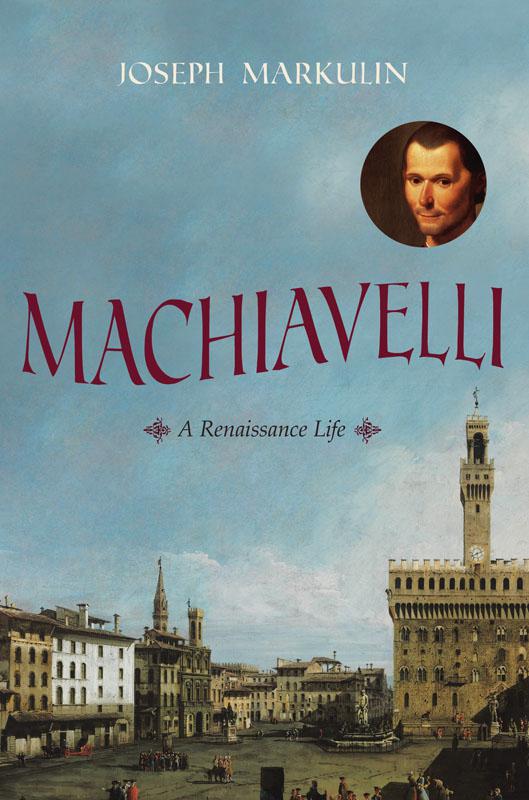

Upper cover image: detail of Niccol Machiavelli or Portrait of Machiavelli ,

by Santi di Tito, oil on canvas dated to the second half of the sixteenth century

Lower cover image: The Piazza della Signoria in Florence , by Bernardo Bellotto,

ca. 1742, located at Szpmvszeti Mzeum, Budapest, Hungary

Cover design by Jacqueline Nasso Cooke

Inquiries should be addressed to

Prometheus Books

59 John Glenn Drive

Amherst, New York 142282119

VOICE: 7166910133

FAX: 7166910137

WWW.PROMETHEUSBOOKS.COM

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Markulin, Joseph.

Machiavelli : a renaissance life / Joseph Markulin.

pages cm ISBN 978-1-61614-805-8 (pbk.) ISBN 978-1-61614-806-5 (ebook)

1. Machiavelli, Niccol?, 1469-1527. 2. Statesmen--Italy--Biography. 3. Intellectuals--Italy--Biography. 4. Political scientists--Italy--Biography. 5. Authors, Italian--Biography. 6. Italy--History--1492-1559--Biography. 7. Florence (Italy)--History--1421-1737--Biography. I. Title.

JC143.M4M3785 2013

320.1092--dc23

2013022352

Printed in the United States of America

For Sandy, a shooting star...

Ercole dEste was so filled with awe at the sound of his own name that he often choked with emotion when called upon to pronounce it. Not that he was an excessively vain man. Rather, it was an inordinate pride in his ancestry that caused him to treat his name with a respect bordering on veneration.

The Este family had ruled Ferrara for over two centuries, and for the most part, they had ruled it wisely, promoting the general welfare by developing industry and agriculture, building broad roads, and straightening streets. They had supported the fledgling university and had persuaded the eminent Greek scholar Guarino da Verona to come there and lecture. They had built a public park within the narrow confines of the city walls, a thing unheard of at the time. And, of course, most importantly, they had strengthened the citys fortifications.

Ferrara was a small state but a rich one, and like all the other city-states of northern Italy, she was constantly at war. Political turbulence had become a way of life for the dozens of arrogant dukes who were incessantly attacking or being attacked, marching off to battle or waiting out sieges in their impregnable fortresses. Ferrara, by comparison, was at peace more often than many of the others. The Este, through the judicious use of marriage bonds and the skillful weaving of secret alliances, had brought calm and relative stability to the city.

Ercole (Hercules) dEste managed his affairs well. He had to, for he literally owned the realm, and his prosperity, not to say survival, depended on it. He owned the land and all its bounty; he owned the grain and the vines; he owned the river and the fish in the river; he owned the mines, the mills, and the cattle; and last, he owned the people. He had complete authority to do anything he wished. His power was absolute. He could make laws or dissolve them. He could promote interests friendly to himself and his family, and he could kill his enemies with impunity. He reserved the right to impose taxes, to punish crimes, and to declare war. But as tyrants go, Ercole was one of the less abusive ones, and he retained the love and respect of his subjects.

Attached to the court of the Este family was an illustrious physician by the name of Savonarola. Although originally from Padua, Savonarola had secured his post in Ferrara on the basis of his reputation as a world-famous authority on the curative properties of spas and mineral waters. But more than that, he was a staunch proponent of the beneficial effects of alcohol, which he was always quick to prescribe for any illness. He maintained that it fortified the blood, revived the heart, dissipated superfluous body fluids, prevented fevers, and aided the digestion. If taken in sufficient quantities, it also cured colic, dropsy, paralysis, worms, and scurvy. It calmed toothaches, gave protection against the plague, and drove away wind. In alcohol, the physician Savonarola had found his panacea, and his prescriptions were eagerly received by the Este and their court. His position was secure, and he was much sought out as an eminent man of science. Upon retirement, his duties passed to his son, who faithfully executed, in every detail, the precepts and traditions of the father.

When Girolamo Savonarola was a boy, it was decided that he, too, like his father and his grandfather before him, would study medicine in order to assume his rightful post as third-generation court physician. But the boy was ill-suited to the role. From the way his father talked, young Girolamo had the distinct impression that the court physician had been engaged more as a tavern keeper than as a doctor. Medicine as practiced by the Savonarolas was as much a matter of dispensing cheer and goodwill as anything else.

Unlike his bibulous progenitors, Girolamo was a gloomy, introspective child. Physically, he was small, ugly, and clumsy. He was pale and withdrawn, and he cared little for the company of other children. He preferred to be alone, and the thing that seemed to give him the most pleasure in life was his lute. He would play for hours sad, plaintive melodies that he composed himself. And he would compose verses, too, and set them to music.

Although he showed no particular interest in the study of medicine, he mastered his lessons easily. And, while outwardly he appeared dazed and inattentive, it soon became clear to his teachers that he was possessed of a brilliant mind. Brilliant but restless and nervous. He would dispense with his medical texts and required lessons in short order and then withdraw to the solitude of his room, to his music, to his poetry, and to the one book that brought him solacethe sacred scriptures. He read the prophets avidlyJeremiah in particular. But the text that he had read and reread perhaps a hundred times and of which he never tired, what sparked his mind and fired his imagination, was the Book of the Apocalypse.

At the age of sixteen, his studies were progressing satisfactorily, and the elder Savonarola decided it was time for his son to be introduced to the court and its pleasures, so that he could begin his practical training for the profitable position that awaited him. The pompous doctor exploded when he saw his son bundled for the august occasion into his usual plain clothesa simple grey frock with wool stockings.

You expect to go to court dressed like that! The Duke will laugh at you! Theyll mistake you for a lout, for a stable boy! You! A Savonarola! Who would ever believe it?

Next page