This edition published in 2012 by Arcturus Publishing Limited

26/27 Bickels Yard, 151153 Bermondsey Street, London SE1 3HA

Copyright 2012 Arcturus Publishing Limited

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person or persons who do any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Picture Credits

Images courtesy of Getty, Mary Evans, National Archive, Rex, Topfoto and Ullstein. For more information contact info@arcturuspublishing.com.

ISBN: 978-1-84858-953-7

AD002432EN

Contents

Introduction: The Myth of Jack the Ripper

O n the gloomy afternoon of Tuesday, 2 October 1888, carpenter Frederick Wildborn entered a dank, dark cellar in the new Metropolitan Police headquarters which was then under construction on the Thames Embankment and discovered a large brown paper parcel tied with string. When it was opened it was found to contain the dismembered, decomposing torso of an unidentified female whose severed arm had been fished out of the Thames a few weeks earlier. Her head and the remaining limbs were never recovered. This gruesome discovery was the first in a series of macabre torso murders which were to haunt the recently formed Criminal Investigation Department (CID) over the next 12 months.

At first the police suspected they might be the work of Jack the Ripper, the Whitechapel murderer, who had apparently and inexplicably gone to ground after committing a number of brutal murders earlier that autumn, but the nature of the mutilations suggested otherwise. Evidently there was more than one psychopath stalking the streets of London, despatching his victims with impunity under the very noses of Scotland Yard.

Incredibly, neither the Ripper nor the torso murderer were ever identified, arrested or charged. But while the latter remains a footnote in the history of crime, his evil twin continues to exert a macabre fascination more than a century later. And its all in the name a sobriquet created by an unscrupulous but enterprising journalist to keep the killings on the front page and raise the stakes in a cut-throat circulation war. Thanks to this macabre appellation, Jack the Ripper is now lodged in the popular imagination as the personification of the debauched Victorian gentleman, a real-life Mr Hyde freed from the subconscious of respectable society to embody its repressed sexuality. And yet, the reality was very different. The evidence presented in the following pages clearly contradicts the popular image of the top-hatted and cloaked aristocrat cutting through the swirling London fog with a small black bag, hell-bent on ridding the streets of sin.

Hoaxes and wild theories

Unfortunately, any effort to identify the Ripper is made more difficult by the fog of confusion generated by those keen to advance their spurious speculations and fanciful conspiracy theories involving secret societies, eminent surgeons, Satanists and even members of the royal family occasionally all four whom we are asked to believe happily came together in a convoluted conspiracy to save England and the Establishment.

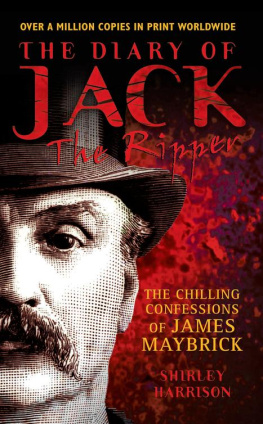

Some of the theories that have been put forward are more plausible than others, but nothing pertaining to the Whitechapel murders can be taken at face value. In addition to the Dear Boss letters, which gave birth to the name Jack the Ripper and which are now considered to have been a hoax, there have been more recent attempts to promote seemingly forged documents as genuine artefacts of the period, the notorious Maybrick Ripper Diary being a case in point. More recently an aggressive publicity campaign by crime writer Patricia Cornwell to prove the case against her favoured suspect, the painter Walter Sickert, has only served to add more misinformation to the mix.

In contrast, this book has arisen from a thorough and impartial investigation focusing on a re-examination of the facts as contained in the official Scotland Yard files, the original post-mortem reports and contemporary witness statements as well as the private correspondence of detectives and police officials who had been assigned to, or had overseen, the case.

I have aimed to strip away decades of myth and misconception to reveal which, if any, of the usual suspects has a case to answer, while remaining aware that the murders may not have been the work of a single individual.

If these crimes were being investigated today, what would the authorities consider to be the vital clues? How would their profilers describe Englands first serial killer and which of the usual suspects would they be looking to convict?

Paul Roland

Chapter 1: The Rippers World

I n 1887 Queen Victoria celebrated her Golden Jubilee with much pomp and pageantry. Since her accession, the British Empire had swallowed up colonies as far apart as Canada and the Caribbean, India and Australia, Africa and Asia and was now so extensive that it was said the sun never set upon it.

Britannia not only ruled the waves, but through the notable Christian virtues of self-discipline, enterprise and honourable conquest she also possessed one quarter of the surface of the earth, its people and their wealth. The dour, white-haired mother of the nation now presided over the largest and most prosperous empire the world had ever seen. Britains industrialists had capitalized on the Empires formidable resources in both manpower and material, so that by 1870 the United Kingdom could boast foreign trade figures four times greater than those of the United States.

Industrial marvels

London, the jewel in this imperial crown, had been linked to all of Britains major cities by a rapidly expanding rail network in a formidable undertaking to rival that of the building of the Egyptian pyramids. Passengers could now travel to and from the metropolis in comfort on journeys that took hours instead of days and traders could transport both raw materials and finished goods to a reliable timetable, making the erratic stagecoach and canal system almost redundant at a stroke. The project had been overseen by the great architect of Victorian regeneration, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. But though Brunel had the vision, the laborious task was realized by a largely immigrant workforce who cut through the countryside with pick and shovel to lay 25,000 km (15,530 miles) of track, each length of rail having to be manhandled into position and every spike driven in by hand. Not even nature was permitted to impede the progress of this grand imperial project. Hills were dynamited, forests were flattened and the river Avon was spanned by Brunels iron suspension bridge which was duly declared a marvel of 19th-century engineering.

Productivity had not slackened since the Queen had opened the Great Exhibition in the vast glass-covered Peoples Palace (later Crystal Palace) in 1851 to display the best of British ingenuity and enterprise. British goods and raw materials were being exported around the world in British-built ships, earning the country the title the workshop of the world, although many unscrupulous employers seized on this appellation as an entitlement to exploit their underpaid female workers and to ignore child labour laws.

Family expectations

Victoria, who had nine children and 37 great-grandchildren, was fiercely proud of her image as the widowed mother of the nation and she expected Britains middle- and upper-class daughters to be as dutiful and unselfish as she had been. They were to be unquestioningly obedient to their fathers while they lived at home and subservient to their husbands after their marriage. Denied the vote and equal rights, they were also to forgo any intellectual aspirations and instead devote themselves to their husbands happiness. As for their physical needs, they were expected to repress their own sexuality, which meant squeezing themselves into tortuously tight corsets and shapeless dresses which coyly covered every inch of flesh, rendering them as sexless as a tea cosy. Some inhibited individuals went so far as to cover the legs of their pianos to avoid embarrassment.

Next page