CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

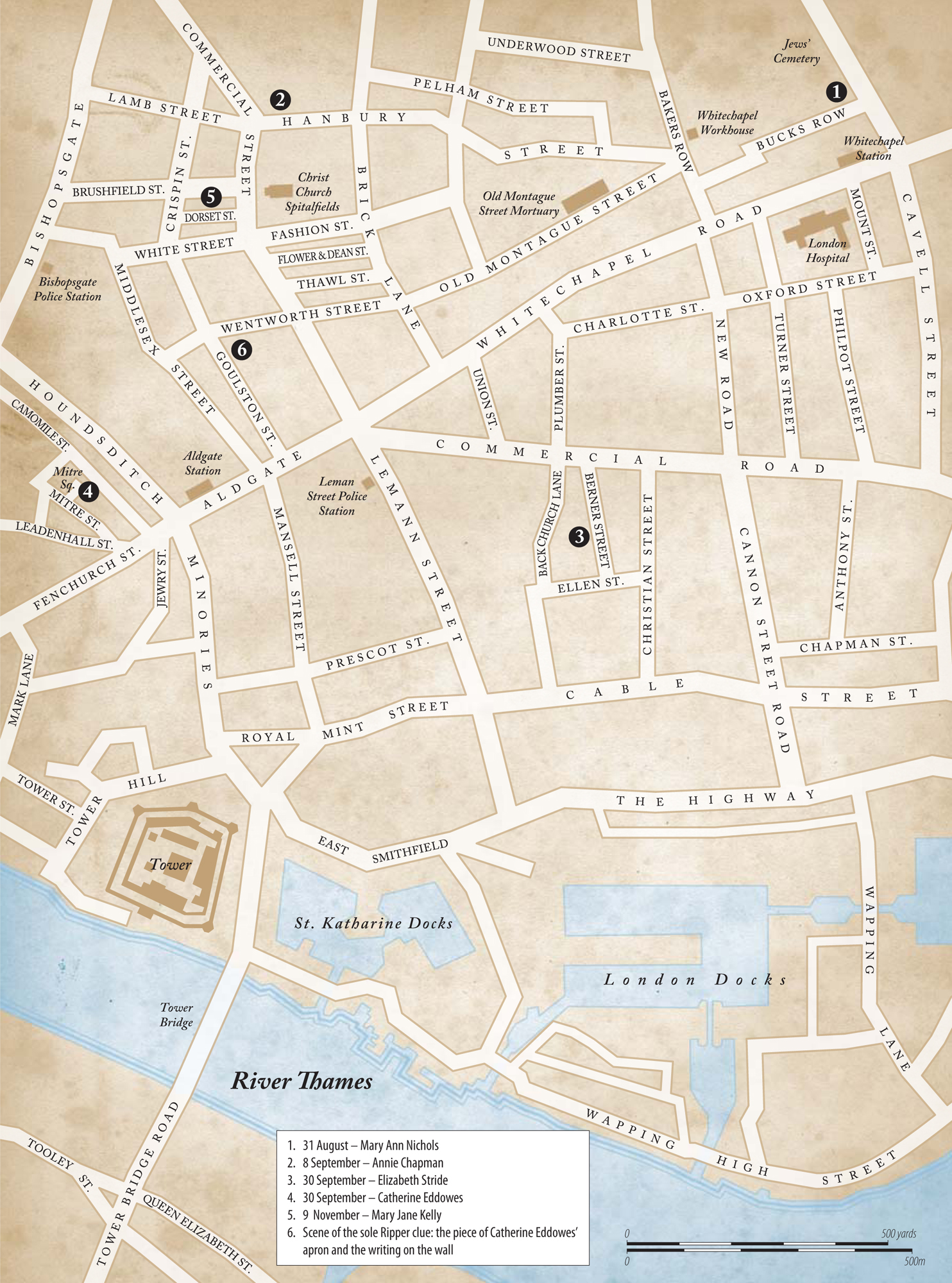

Given the long shadow cast by Jack the Ripper over the annals of crime, it can be a surprise to learn that the killer prowled the streets of the East End for only ten short weeks in the autumn of 1888 and that his tally of murders may have been as few as five. If the crime spree was short, the reign of terror has been long. One hundred and twenty-five years on from The Whitechapel Murders, the figure of Jack the Ripper still haunts the popular imagination. Walking tours nightly lead tourists around what little remains of the Rippers Whitechapel hunting ground; new or reheated theories as to the Rippers identity regularly appear in the press and online; and Jack, complete with top hat, cape, and Gladstone bag, remains a centrepiece in both Madame Tussauds Chamber of Horrors and the London Dungeons recreation of dark scenes from Londons past.

Why this enduring fascination with a Victorian villain? The main reason must of course be the fact that Jacks identity remains unknown. The story is the quintessential whodunnit, benefiting from a long parade of suspects but no conclusive evidence against any of them.

Hitchcocks The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927). The landlady extends a cautious welcome to the mysterious gentleman enquiring about her vacant upper rooms. His only luggage is a small leather bag. (AF archive / Alamy)

Yet the Rippers endurance is also due to an extraordinary collision of fact and fiction. As well see in this book, the real story of the Ripper was infused from the start with elements from folklore, Gothic fiction, melodrama, and the sensation novel. These elements ensured that the story of the Whitechapel Murders would be remembered and retold for years to come and that the Ripper would outlive his crimes and his era as a character of legend, a dramatis persona.

The extraordinary process by which Jack moved from fact to fiction is the subject of this book. After a look at the crimes and the police investigation of 1888, we will examine the prime suspects in the case, then and now, before exploring the ways in which the Ripper has lived on in the popular imagination.

The book will not unmask Jack the Ripper but it will take a good close look at the many faces we have given him, and continue to give him, through time.

CHAPTER ONE: OH, MURDER!

The Whitechapel Murders of 1888

The crimes that started it all were undoubtedly cruel and violent, though they were fewer than we might expect given the place afforded the Ripper in the annals of crime. For there were five victims and five victims only according to Sir Melville MacNaughten, assistant chief constable of the CID (Criminal Investigation Department), in his 1894 memoir of the case. Historians of the crimes, or Ripperologists, differ on this tally some suggesting there were fewer victims, others more and like much about the Ripper story, it is possible that we shall never know for sure. Our greater experience and understanding of serial killers in modern times has shown that it is common for unsolved or cold cases to be linked many years after the event with a killer convicted and incarcerated for other crimes. As recently as October 2013, an attempt has been made to link the Yorkshire Ripper with an unsolved murder in London in September 1979. Let us follow Sir Melvilles lead and start with the canonical five murders before considering the Victorian cold cases that just might have been Ripper murders.

(Mary Evans)

All of the Rippers known victims were unfortunates in the parlance of the day prostitutes living close to or even beneath the poverty line. All lived in Spitalfields and Whitechapel and, with the exception of final victim, Mary Jane Kelly, were in middle age at the time of their deaths. Recounting, however briefly, their last known movements and last recorded words not only builds up a picture of the Ripper crimes, but also gives a poignant glimpse of the fragile and vulnerable lives of East End streetwalkers in late Victorian London.

Mary Ann Nichols

Discovered in the early hours of Friday 31 August 1888

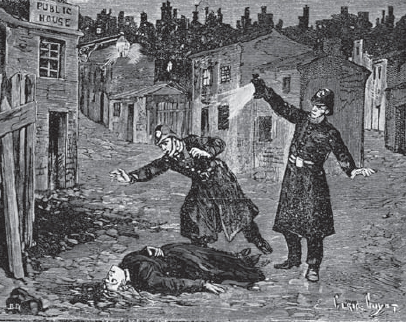

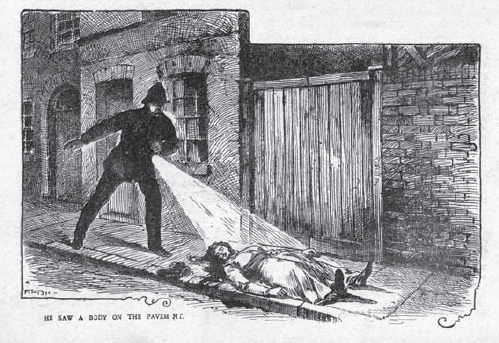

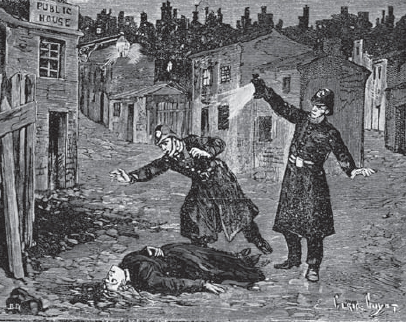

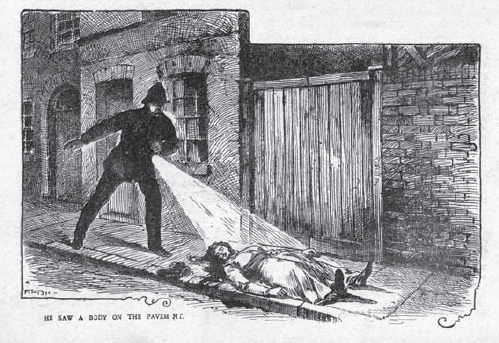

The first certain Ripper murder took place just as the summer of 1888 was drawing to a close. In the early hours of Friday 31 August, market porter Charles Cross was threading his way through the streets of Whitechapel to begin a long days work. As he made his way down the dimly lit thoroughfare known as Bucks Row, he came across the body of a short, middle-aged woman, slumped against the boundary wall of some stables. Assuming the woman to be drunk or injured but alive, Cross sought the help of John Paul, a second market porter, who was approaching him warily from further along Bucks Row. Paul checked the woman for vital signs, and, finding her cold to the touch, he and Cross set off together in search of a policeman. Just minutes later, the patrol beat of Police Constable 97J John Neil brought him through Bucks Row, led him up to the same stable gateway, and placed him at the centre of one of the most iconic scenes in the history of crime. Peering into the darkness at the recumbent shape on the pavement, Neil shone his bull lantern onto the body of Mary Ann Nichols, thus revealing the first certain victim of Jack the Ripper, blood oozing from a deep gash in her throat.

The identity of this first Ripper victim, and the full extent of her injuries, would only become clear over the course of that last Friday in August. After a brief examination in situ by Dr Rees Ralph Llewellyn of Whitechapel Road, the body was conveyed to a nearby mortuary where Dr Llewellyns more detailed examination and autopsy revealed severe mutilation to the abdominal and pubic regions. Examination of the womans clothing and few personal effects implied a connection with Lambeth Workhouse and suggested she had most recently been living in a local common lodging house or dosshouse. Enquiries along these lines soon brought positive identification of the body as that of Mary Ann or Polly Nichols, who had indeed spent stints in the Lambeth Workhouse and whose most recent address was Wilmotts Lodging House at 18 Thrawl Street, Whitechapel. It was the need to procure her four pence doss money that had taken Polly out on to the dark streets of the East End the previous night. She had been optimistic of finding it, boasting to friends that a new addition to her apparel would pay dividends See what a jolly bonnet Ive got now. The last recorded sightings of Polly were her drunken exit from The Frying Pan pub in Brick Lane, at 12.30 a.m., and her drunken adieu to lodging house roommate Emily Holland at the corner of Brick Lane and Whitechapel High Street at about 2.30 a.m.

(Mary Evans)

The investigations at the mortuary concluded with the positive identification of Pollys body by her estranged husband William Nichols, who reportedly took his solemn leave of her with the words Seeing you as you are now, I forgive you for what you have done to me. His words as he left the mortuary are also recorded: It has come to a sad end at last an end made complete a few days later when Polly Nichols was laid to rest in Ilford Cemetery.