To Rosie and Molly,

with love and thanks for the

gentle guidance

Contents

W e gratefully acknowledge the following for the material and the assistance they have provided: Bishopsgate Institute, British Library Picture Library, Evans/Skinner Crime Archive, Guildhall Library and Art Gallery, Library and Museum of Freemasonry, London Library, London Metropolitan Archives, Metropolitan Police Archives Section, Metropolitan Police Commissioners Library, the National Archives, Kew.

Both authors would like to thank the following individuals for their support: Maggie Bird, Bernard Brown, Martin Cherry, Rob Clack, Michael Conlon, Nicholas Connell, John Fisher, the late Melvin Harris, Jon Ogan, Roger J. Palmer, Stephen P. Ryder, Neal Shelden, the late Jim Swanson, Jeremy White, Richard Whittington-Egan, Sarah Wise.

All the images reproduced here belong to the authors collections unless otherwise stated.

R EVIEWING the literature on the subject of Jack the Ripper, both authors were struck that despite the plethora of books, nobody had approached the subject from the police viewpoint. Usually suspect theories dominate any account of the Whitechapel murders and the police, notably Commissioner Sir Charles Warren, come in for abuse, ridicule and charges of incompetence at best. We decided to look at the investigation as far as was possible from the police perspective, including only suspects known to the original police investigators and their contemporaries. This means that well-known theories, such as those involving the Duke of Clarence (Queen Victorias grandson), the artist Walter Sickert, James Maybrick and many others have been excluded from this book. That they will not have to go through yet another reworking of these ideas will no doubt come as a great relief to the reader, just as it did to the authors.

The police documents that survive, including letters from the public, can be found in the National Archives at Kew and in the Corporation of the City of London Records now deposited (temporarily) in the London Municipal Archives. Stewart Evans spent more than five years transcribing the handwritten police documents to get as accurate a record of the case as was possible. His work was subsequently published, in collaboration with Keith Skinner, as Jack the Ripper: The Ultimate Source Book. This was our primary documentary source for the Scotland Yard investigation. What survives is only a fraction of the original documentation, however. Much was destroyed because of pressure on storage space. Some was borrowed or stolen by contemporaries and their successors, and worse, by the modern-day document thief still active in the national archives. Contemporary newspapers covered the investigation in great detail and we were able to use them to expand upon the available material still further. Newspaper reporters dogged the heels of the detectives, making the investigations more difficult, but adding to the record extra detail that otherwise might have been lost.

To understand the investigation more completely, it is necessary to show how the two London police forces, the Metropolitan and the City, worked both at the investigative and the beat level. This has led us to include here explanations of force structures, organisation and methods of work. The authors own experience gave them some insight because some of the work practices discussed were still continuing when, armed only with the Victorian truncheon and whistle, they pounded their beats in the swinging sixties.

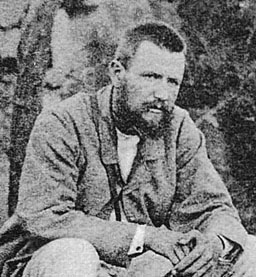

It is necessary, too, to clear away some of the misconceptions about the Victorian chain of command. Popular belief greatly influenced by several movies which have him as their hero, is that Inspector Abberline was in charge of the case and the key investigator. While important, he was much further down the chain of command than is generally believed. The key players for the Metropolitan Police were Sir Charles Warren, the Commissioner; James Monro, who was his head of CID; and Dr Robert Anderson, who was to replace Monro when he resigned in the summer of 1888. To understand the relationship between these men and the politicians at the Home Office it is necessary to explore the background to their careers and to examine why there was such conflict within Scotland Yard at the time of the Whitechapel murders. Warren, it became clear, had to play the biggest role in this book and without understanding his past it is almost impossible to understand his behaviour during his period as commissioner. This made it necessary to go back to the time when he was a soldier-archaeologist, the Indiana Jones of his day, which is why the book begins with the early career of Captain Warren in Jerusalem. His subsequent treatment by Home Secretary Henry Matthews generally gets downplayed in examinations of the Ripper case, which is unfair to Warren, but it is instructive to note that Monro, when he succeeded Warren, was treated hardly more fairly. When he in turn resigned it must have constituted something of a record for a home secretary to lose two commissioners in under two years.

Warrens character and the effect he had on the investigation form the spine of this story. With the police angle in mind, we have concentrated on examining the ideas and suspect theories put forward by the leading officers in the case, especially Sir Robert Anderson, who claimed that the identity of the murderer was a definitely ascertained fact. If any sort of solution to this case does exist, it has to be found in the police sources. If it is not there, then it may be safely assumed not to exist at all.

Stewart P. Evans

Donald Rumbelow

Letters, reports and notes are reproduced here in their original form without the introduction of modern punctuation or spelling, which could, the authors feel, unintentionally alter the writers original meaning.

O NE

T HE underground passage through which the young army engineer and his sergeant had to travel was a mere 4 feet wide and had smooth, slippery sides. Worse still, it was filled with sewage 5 to 6 feet deep. Swimming was impossible and the planks they were planning to float on looked certain to sink under their weight. Casting about for an alternative, they managed to procure three old doors and, with candles in their mouths and measuring instruments in their pockets, they began to leap-frog their way through the tunnel, each man floating on a door and passing the increasingly slippery third one from the back to the front of the convoy. As they slowly moved deeper into the tunnel the constant sucking of the sewage and the increasing difficulty of passing the third door to the front set up violent tipping motions which constantly threatened to overturn them. Fortunately their luck held. Had it not done so, as Lieutenant Warren said, What honour would there have been in dying like a rat in a pool of sewage?

Charles Warren, this subterranean archaeologist, was born in 1840. He was the second son of Major-General Sir Charles Warren, a professional soldier, who at 16 had served under Wellington as an ensign and was twice wounded while fighting in China, India and the Crimea. He and his elder son John were in the same regiment; both were wounded at the battle of the Alma in 1854. John died of his wounds. Charless mother died when he was 6 years old and he determined quite early to follow his father and brother into the army. He was good at mathematics and had no difficulty in getting into the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst and subsequently Woolwich Academy, where he enrolled in February 1856.

Two very noticeable traits remained with him from his school years. As a boy he was fond of poetry and enjoyed learning lessons by turning them into rhyming Latin or Greek. This facility stayed with him and was eventually noted in the press when a correspondent, recalling Warrens frequent uncontrollable urge to drop into poetry while drafting police orders, gave this example:

Next page