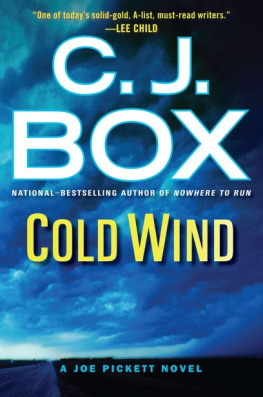

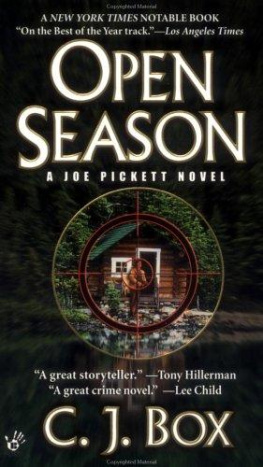

The sixth book in the Joe Pickett series, 2006

For Molly Jo

and Laurie, always

Family quarrels are bitter things. They dont go by any rules. Theyre not like aches or wounds; theyre more like splits in the skin that wont heal because theres not enough material.

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

The great plain drinks the blood of Christian men and is satisfied.

O. E. RLVAAG, GIANTS IN THE EARTH

Twelve Sleep County, Wyoming

WHEN RANCH OWNER OPAL SCARLETT VANISHED, NO one mourned except her three grown sons, Arlen, Hank, and Wyatt, who expressed their loss by getting into a fight with shovels.

Wyoming game warden Joe Pickett almost didnt hear the call over his radio when it came over the mutual-aid channel. He was driving west on Bighorn Road, having picked up his fourteen-year-old daughter, Sheridan, and her best friend, Julie, after track practice to take them home. Sheridan and Julie were talking a mile a minute, gesticulating, making his dog, Maxine, flinch with their flying arms as they talked. Julie lived on the Thunderhead Ranch, which was much farther out of town than the Picketts home.

Joe caught snippets of their conversation while he drove, his attention on his radio and the wounded hum of the engine and the dancing gauges on the dash. Joe didnt yet trust the truck, a vehicle recently assigned to him. The check-engine light would flash on and off, and occasionally there was a knocking sound under the hood that sounded like popcorn popping. The truck had been issued to him as revenge by his cost-conscious superiors, after his last vehicle had burned up in a fire in Jackson Hole. Even though the suspension was shot, the truck did have a CD player, a rarity in state vehicles, and the sound track for the ride home had been a CD Sheridan had made for him. It was titled Get with it, Dad in a black felt marker. Shed given it to him two days before after breakfast, saying, You need to listen to this new music so you dont seem so clueless. It may help. Things were changing in his family. His girls were getting older. Joe was not only under the thumb of his superiors but was apparently becoming clueless too. His red uniform shirt with the pronghorn antelope Game and Fish patch on the shoulder and his green Filson vest were caked with mud from changing a tire on the mountain earlier in the day.

I think Jarrod Haynes likes you, Julie said to Sheridan.

Get out! Why do you say that? Youre crazy.

Didnt you see him watching us practice? Julie asked. He stayed after the boys were done and watched us run.

I saw him, Sheridan said. But why do you think he likes me?

Cause he didnt take his eyes off of you the whole time, thats why. Even when he got a call on his cell, he stood there and watched you while he talked. Hes hot for you, Sherry.

I wish I had a cell phone, Sheridan said.

Joe tuned out. He didnt want to hear about a boy targeting his daughter. It made him uncomfortable. And the cell-phone conversation made him tired. He and Marybeth had said Sheridan wouldnt get one until she was sixteen, but that didnt stop his daughter from coming up with reasons why she needed one now.

In the particularly intense way of teenage girls, Sheridan and Julie were inseparable. Julie was tall, lithe, tanned, blond, blue-eyed, and budding. Sheridan was a shorter version of Julie, but with her mothers startling green eyes. The two had ridden the school bus together for years and Sheridan had hated Julie, said she was bossy and arrogant and acted like royalty. Then something happened, and the two girls could barely be apart from each other. Three-hour phone calls between them werent unusual at night.

I just dont know what to think about that, Sheridan said.

Youll be the envy of everyone if you go with him, Julie said.

He doesnt seem very smart.

Julie laughed and rolled her eyes. Who cares? she said. Hes fricking awesome.

Joe cringed, wishing he had missed that.

He had spent the morning patrolling the brushy foothills where the spring wild turkey season was still open, although there appeared to be no turkey hunters about. It was his first foray into the timbered southwestern saddle slopes since winter. The snow was receding up the mountain, leaving hard-packed grainy drifts in arroyos and cuts. The retreating snow also revealed the aftermath of small battles and tragedies no one had witnessed that had taken place over the winter-six mule deer that had died of starvation in a wooded hollow; a cow and calf elk that had broken through the ice on a pond and frozen in place; pronghorn antelope caught in the barbed wire of a fence, their emaciated bodies draping over the wire like rugs hanging to dry. But there were signs of renewal as well, as thick light-green shoots bristled through dead matted grass near stream sides, and fat, pregnant does stared at his passing pickup from shadowed groves.

April was the slowest month of the year in the field for a game warden, especially in a place with a fleeting spring. It was the fifth year of a drought. The hottest issue he had to contend with was what to do with the four elk that had shown up in the town of Saddlestring and seemed to have no plans to leave. While mule deer were common in the parks and gardens, elk were not. Joe had chased the four animals-two bulls, a cow, and a calf-from the city park several times by firing.22 blanks into the air several times. But they kept coming back. The animals had become such a fixture in the park they were now referred to as the Town Elk, and locals were feeding them, which kept them hanging around while providing empty nourishment that would eventually make them sick and kill them. Joe was loath to destroy the elk, but thought he may not have a choice if they stuck around.

The changes in his agency had begun with the election of a new governor. On the day after the election, Joe had received a four-word message from his supervisor, Trey Crump, that read: Hell has frozen over, meaning a Democrat had been elected. His name was Spencer Rulon. Within a week, the agency director resigned before being fired, and a bitter campaign was waged for a replacement. Joe, and most of the game wardens, actively supported an Anybody but Randy Pope ticket, since Pope had risen to prominence within the agency from the administrative side (rather than the law-enforcement or biology side) and made no bones about wanting to rid the state of personnel he felt were too independent, who had gone native, or were considered uncontrollable cowboys-men like Joe Pickett. Joes clash with Pope the year before in Jackson had resulted in a simmering feud that was heating up, as Joes report of Popes betrayal made the rounds within the agency, despite Popes efforts to stop it.

Governor Rulon was a big man with a big face and a big gut, an unruly shock of silver-flecked brown hair, a quick sloppy smile, and endlessly darting eyes. In the previous years election, Rulon had beaten the Republican challenger by twenty points, despite the fact that his opponent had been handpicked by term-limited Governor Budd. This in a state that was 70 percent Republican. Rulon grew up on a ranch near Casper, the grandson of a U.S. senator. He played linebacker for the Wyoming Cowboys, got a law degree, made a fortune in private practice suing federal agencies, then was elected county prosecutor. Loud and profane, Rulon campaigned for governor by crisscrossing the state endlessly in his own pickup and buying rounds for the house in every bar from Yoder to Wright, and challenging anyone who didnt plan to vote for him to an arm-wrestling, sports-trivia, or shooting contest. The word most used to describe the new governor seemed to be energetic. He could turn from a good old boy pounding beers and slapping backs into an orator capable of delivering the twelve-minute closing argument by Spencer Tracy in

Next page