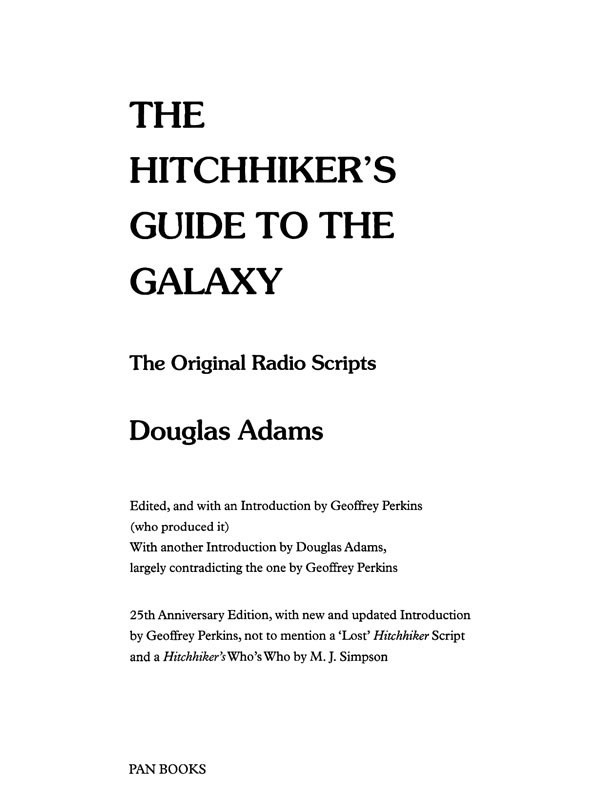

To the BBC Radio studio managers

Publishers Note

Hitchhikers was spelled in almost all possible ways from its creation in 1978: in October 2000 Douglas Adams decided that everyone should spell it the same way from then on. In the 25th Anniversary Edition we have used his preferred spelling in the new material, and in the original material it is printed as it was in 1985.

Introduction to the First Edition

The first time I can remember coming across Douglas Adams he was standing on a rickety chair making a speech., and the thing I remember most about that was that it was really rather a strange thing to do, since he was already some six inches taller than anyone else in the room. He also pressed on with his speech despite being aggressively heckled by members of the cast of the Cambridge Footlights show that he had just directed.

It was plain here was someone prepared to stick his neck out further than most people, someone who would carry on in the face of adversity, and someone who would shortly fall off a chair. I was right on all three counts.

Some years later when I was producing the radio series of The Hitch-Hikers Guide to the Galaxy I was also to learn that he was an amazingly imaginative comic writer whose desire to push back the barriers of radio comedy was only matched by his desire for large meals in restaurants.

I came to work for BBC Radio from a shipping company in Liverpool. I only went there because when I told the University appointment board that I didnt know what I wanted to do they immediately told me to go into shipping. It was only afterwards that I realised they probably recommend everyone who comes in on a Wednesday and doesnt know what they want to do to go into shipping. On Thursdays its probably accountancy, and so on. I sat around wondering what I was doing there for six months until I was recommended to the BBC as a potential producer by Simon Brett, who also started Douglas off with Hitch-Hikers. We both owe him an enormous debt.

Prior to the shipping company I had been at Oxford and directed the University revue at the Edinburgh Festival for the previous two years. This made me an unlikely person to work with Douglas, he being a Cambridge man, not to mention nearly twice my size. If you saw us together you would immediately think of Simon and Garfunkel. Except that I dont write songs and Douglas doesnt sing. Well, he does, but he shouldnt. He is, however, a very good guitarist (unlike Art Garfunkel) and is very keen on Paul Simon, whom he exactly resembles in no way at all. In fact Paul Simon actively refused to meet Douglas in New York when he heard how tall he was. This may have been because he had heard that Douglas was prone to falling off rickety chairs and to breaking his nose with his own knee and so was liable to step on him accidentally and squash him.

Douglas is also the only person I know who can write backwards. Four days before one of the Hitch-Hikers recordings he had written only eight pages of script. He assured me he could finish it in time. On the day of the recording, after four days of furious writing, the eight pages had shrunk to six. Some people would think this was a pretty clever trick but Ive been with Douglas when hes writing and I know how he does it. When he wants to change anything, a word or a comma, he doesnt just cross it out and carry on; he takes the whole page out of the typewriter and starts all over again from the top. Yes, he is something of a perfectionist but he would also do almost anything to avoid having to write the next bit. His other favourite way of putting off writing the next bit is to have a bath. When a deadline is really pressing he can have as many as five baths a day. Consequently, the later the script the cleaner he gets. You cant fault him for personal hygiene in a crisis.

But of course much of the strength of Hitch-Hikers comes from the fact that Douglas has sweated over every word of it. Its not just funny, it is also very good writing; and one of the few comedy shows where people dont think that the actors have made it all up as they went along. And at least Douglas was never quite as bad at overrunning deadlines as Godfrey Harrison, who wrote the popular 50s radio comedy show The Life of Bliss, who often finished the script some hours after the audience had all gone home.

Fortunately we didnt have to worry about the audience leaving. Amazingly there was some debate when the programme started about whether we should have a studio audience, since at that time nearly all radio comedy shows had one. In fact an audience for Hitch-Hikers would have needed about a week of spare time, since thats about how long it took to make each show.

Theyd also have been thoroughly confused by the whole thing, since much of the time the show was recorded out of order, rather like a film, and only half the actors in any scene would actually be visible on stage. In fact we evolved a whole new form of radio performance, which Mark Wing-Davey called cupboard acting. All the various robots, computers, Vogons and so on had their voice treatments added after the recordings, so it was necessary to separate them from the other actors, and this we did by putting them in cupboards. During the series several elderly and very distinguished actors were reluctantly shut up in cupboards and only got to talk to the other actors through a set of headphones. Sometimes we would forget all about them and long after their scenes had finished a plaintive voice would be heard in the control box, saying, Can I come out now?The experience was all the odder because we recorded the shows in the Paris, BBC Radios main audience studio, in Londons Lower Regent Street, since at the time it was the only stereo studio with a multi-track tape recorder (albeit only eight tracks). The actors would consequently perform in front of rows and rows of empty seats, and sometimes when three or four aliens were taking part in a scene you could look out of the control box and there would be nobody on the stage at all. Theyd all be in various cupboards dotted around the studio. Sometimes the actors played more than one part, sometimes as many as five parts. This of course was so that they could show off their versatility. It was also so that we could manage to bring the show in somewhere in the region of the budget.

The actors were recorded without all the backgrounds and effects, which were put on afterwards. Contrary to many peoples beliefs most of the sounds are not pure radiophonic sound but were made up by playing around with some of the thousands of ordinary BBC effects discs. Most of the synthesised effects and music were done on an ARP Odyssey, which sounds impressive unless you happen to know that it is in fact a tacky little machine which can be found irritating people in cocktail bars all over the world. The Radiophonic Workshop itself (housed in a pink painted converted ice rink in Maida Vale) is a marvellous lash up of bits and pieces of gadgetry gradually picked up over the years. When we started the series we spent many hours just finding out what some of the equipment could do (or not do in the case of their vocoder, which must have been one of the first ones around, took up a whole room and stubbornly refused to do anything other than emit various vaguely unpleasant hums). However, if we had known how all the equipment worked wed have missed all the fun of playing around with it, and Id have missed all the fun of finding out what the pubs are like in Maida Vale.

More playing around went on in the Paris Studio, where most of the shows were put together. Many of the backgrounds and incidental noises (like Marvins walk) were put on loops of tape which went round endlessly. Sometimes we would have three or four of these loops on the go at any one time and the cubicle would look as if it had been strewn with grim black Christmas decorations. But I cant speak too highly of the efforts of the technical team, led by Alick Hale-Munro. I particularly remember one occasion when, after wed overrun our mixing session for the umpteenth time, I received a stern phone call strictly forbidding me from incurring any more overtime for the studio managers. So at six o clock sharp, I said, Right, thats it, whereupon they all looked at me rather incredulously and said, But were half way through this scene. When I explained I wasnt allowed to let them run over they insisted on finishing the scene and said they had no intention of claiming any overtime. That sort of attitude was undoubtedly a great factor in the success of the show.

Next page