PREFACE

For almost a year I lived at the edge of the ocean, in an old white house with a garden. Sometimes crabs would come up from the beach, find their way into the kitchen and make a tremendous amount of noise, rattling around at night. Sometimes the electricity would go off and we would hunt in the dark for dry matches and go to bed by candlelight. Wild chickens roamed through our garden at dawn and the roosters would crow underneath our windows and wake us up, and sometimes the hens would have a clutch of tiny new chicks with them. Mostly we lived under a hot blue tropical sky but some days it rained all day, from sun up until sundown and on through the night. Once we almost had a hurricane. Two years after we left, four hurricanes hit the island in five weeks and a lot of places that we had known, such as Trader Jacks, were destroyed. Our house was damaged too, but it is an old, strong house and it is still standing.

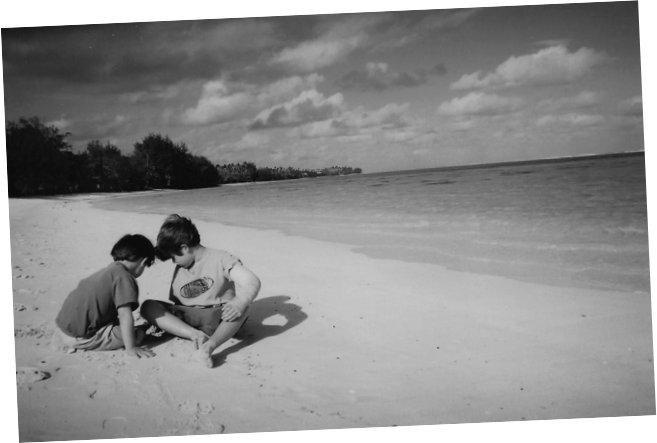

I lived there with my two children. Aiden was seven when we arrived and Tris was three. Their father had left when I was pregnant the second time, so it seemed as though it had always been just the three of us. It didnt seem strange to be living on an island so far away from everything we knew, as long as we were together.

Rarotonga is the main island of the Cook Islands, a country in central Polynesia, west of Tahiti and east of Tonga. Tiny and beautiful, it is surrounded by a wide turquoise lagoon and a sharp coral reef. I had a modest grant to study artists there. My contact in the prime ministers office had lined up a new house for us and had set me up with an associate researcher.

Some of my friends in the US thought I was crazy to pack up my children, leave everything else behind, and head off to a place Id never been before, a place with dengue fever and elephantiasis and dysentery, just because I liked the sound of it. Maybe. But even now, years later, part of me still lives in our old white house on the edge of the sea.

I had been alone ever since Eric, the boys father, had left. I was numb from exhaustion. I had, after all, two small childrenbabies. If you have just one small child, you know this child will have to sleep sometime and that you will sleep then. You may not shower for weeks on end or brush your teeth or even comb your hair, but you will sleep. However, once you are outnumbered with two small children it is possible they will engage in tag-team sleeping so that at least one of them is always awake.

I loved my children. Nevertheless, it was hard raising them by myself. They needed so much from meevery spoonful of food, every bath, every diaper change, every lullaby, every game of peek-a-boo, every piece of laundered clothing, every washed dish, every kiss, every bandage, every everything. Sometimes I would see other mothers hand a child to its father and marvel, wide-eyed and longing, like a prisoner looking at the sky.

Once the boys got a bit older and I wasnt their whole world, the real problems began. Now I was their only protection from the other worldthe one of slings and arrows. The outside world seemed full of people with trumped-up excuses to explain why they were bad-temperedpeople like Aidens first-grade teacher, who told the children she had Cherokee blood and that was why she would never smile. How could I protect my children every moment of every dayeven when I was at work and they were far awayfrom the casual heartlessness of other people? How could I be everything and every where at once? Would I ever have anything approaching a normal life again? I was worn out from trying.

I didnt die, as I feared, but I didnt have any offers of romance either. This may have been because I was tired, miserable and hadnt showered in weeks. I became sadly resigned to a future without men.

But then one day there was Gregg. Its the old story. There you are, blithely playing with fire, and the next thing you know things have got out of handgot out of hand even though you know full well he has a girlfriend. He tells you its over, he hasnt loved her in years. He never loved her, not really. The two most dangerous words in the English language: Only you. Gregg may as well have been holding up a sign that said, Todays specialHeartbreaks half-price. I would have rushed over with my credit card.

At the time, the world seemed a complicated, entangled morass. Not only was there the matter of Aidens teacher but my colleagues at work were entrenched in internecine warfare, the American people had just elected a frighteningly stupid man as president, and Greggs girlfriend seemed inexplicably unwilling to disappear. I just wanted to get away. The idea was that Gregg and the boys and I would go to the South Seas together. We would be alone, far away, on an island in the sun, free of all the complications and entanglements. It was only later it occurred to me that as far as Gregg was concerned there was really just one entanglement, and he could have walked away from her any time he chose.

As a professor, I was entitled to a sabbatical every seven yearsa year without teaching or other duties, during which I was supposed to work on research. My sabbatical year was coming up and it seemed perfect timing. I applied for a grant to study the indigenous art of Rarotonga and was successful. Things were falling into place. Then, ten days before we were scheduled to leave, Gregg told me he wasnt coming.

ARRIVAL

Wednesday, July 31

Arrived paradise stop

beautiful beyond our wildest dreams stop

have eaten no dog stop

yet

stop

It was late July when Aiden, Tris and I left Colorado with a suitcase full of shorts and summer dresses for the flight first to Los Angeles and then on to Tahiti, where we waited to reboard our plane in the dark, echoing airport. Finally at two in the morning we touched down in Rarotonga. It is thrillingly terrifying to land in the dead of night at a strange foreign airport with no one you know to meet you and no idea what will happen next. Rarotonga was such a brief stopover for the plane on its way to Auckland that it had not even been mentioned at the gate at Los Angeles international airport.

Here it was a much bigger deal. A man was playing the ukulele and singing on a small stage in the terminal to welcome the planes arrival. It was too dark to see the ocean, but even from the front of the airport I could hear it. Although it was the middle of the southern winter there seemed to be flowers everywhere. Sleepy-looking people from the hotel threw leis around our necks. Tris twisted his double and put it on his head, looking a little like Julius Caesar. There were also lizards; I would learn that these moko ran around near lights at night and ate bugs.

I stood on the sidewalk by our suitcase, holding Aiden with one hand and Tris with the other, waiting to be loaded on to the van that would take us to our hotel, and tried to realise that this was real, tried to hear the ocean and smell the flowers and impress this moment into my brain forever the moment when we arrived.

First thing next morning, I called the number I had been given for Mr Tarau, the man who would be renting us a house. He wasnt there. Then for most of the rest of the day the phones were out. It was the same the next day. To make matters worse my only government contact turned out to have left the country on the outbound flight of the plane that had brought us in. With a feeling of impending doom, I extended our stay at the hotel. How many more days? the pretty girl at the desk asked. Only two, I said, faking optimism.