No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers.

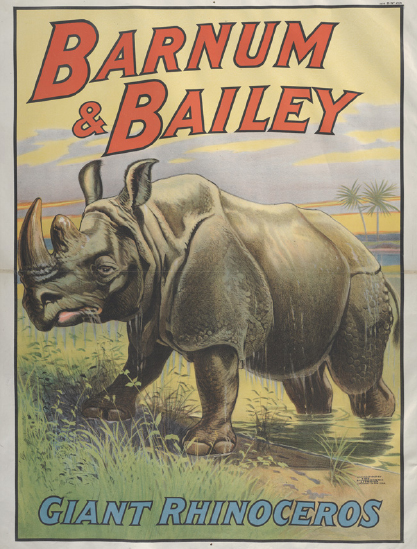

Barnum & Bailey Giant Rhinoceros broadside.

Preface

Do you know what a rhinoceros looks like?

Of course. Its a big, ugly animal.

Eugne Ionesco, Rhinoceros (1959)

Big. Ugly. Violent. Stupid. The rhinoceros has a bad reputation, stretching centuries, even millennia, into our past. When not a villainous symbol of brute force, rhinoceroses are often simply ignored. Although their endangerment in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries has somewhat transformed this image of villainy to one of tragic decline, the heritage of the animals cultural construction, and its unlikely form, does not garner as much public support as the stars of conservation publicity the charismatic megafauna which appeal with the furry cuteness of giant pandas, or the human-like intelligence of gorillas. By contrast, nearly hairless rhinoceroses seem eternally strange. The ways in which we have understood this strangeness is the subject of this book.

I grew up on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, adjacent to New York City. The rhinos I knew best were the stuffed ones at the American Museum of Natural History. These rhinos were always overshadowed by the more dramatic display at the centre of the Akeley Hall of African Mammals where a startled elephant herd animatedly reacts (it would seem) to the visitors in the museum. I distinctly remember sitting in this dark exhibition space, on the bench which surrounds this mounting, and feeling awed at being so near something so large, so strange, so exotic and so expressive.

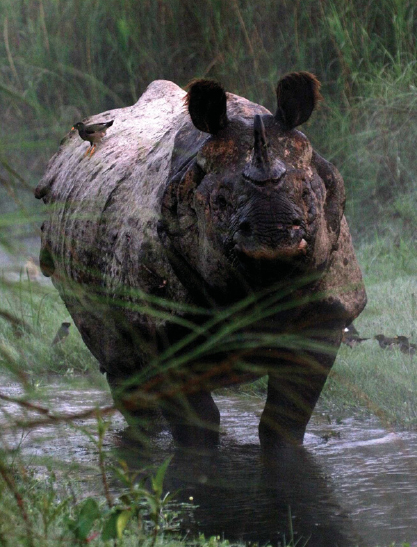

Asian rhinoceros diorama at the American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Also distracting my attention from the rhinos at the far corner of the upper mezzanine were dinosaurs. Even larger and stranger than elephants, mounted dinosaur skeletons were the climax of my museum visit at the impressionable age of six. Little did I realize that the skin I was imagining onto these bones was very like a rhinos skin. Meanwhile, on the other side of Central Park, as I stood in dreamy awe at medieval unicorn tapestries on the wall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I did not see the connection between the elegant white horse of mythology and the one-horned pachyderm I so quickly dismissed.

Although rhinoceroses were not an integral piece of my childhood animal cosmology, their cultural history is closely aligned with the elephants, dinosaurs and unicorns that fascinated me. Just as rhinoceroses are difficult to observe in the wild, so are they elusive in cultural spaces. I have not, I admit, met a rhino in the wild. Nor have I had a close encounter with one in captivity. My rhinoceros expedition sought encounters with the wild animal in cultural spaces. After all, this is how most of us know and have known the species. Does the non-wildness of my encounters make my knowledge of rhinoceroses less real, less true or less authentic? Perhaps. But it might provide an honest gauge of how humans have related and represented rhinos. What does it mean to see an animal imagined in literature, stuffed in exhibits, browsing behind bars? How do we understand an animal so severed from its native context? Are rhinos more themselves when they are in Asia and Africa? If so, how do we categorize, or separate, the real rhino from the captive, the living being from the creature of the imagination?

| The authors close encounter with a rhino (sculpture). |

Confronting a rhinoceros face to face.

Ancient and Mythic

The rhino is a zoological museum piece, a holdover from times long past, a loner that is unadaptable and rather stupid.

Edward R. Ricciuti (1980)

One Valentines Day my boyfriend and I sent each other exactly the same greeting card. The pink front featured two cartoon characters a dinosaur and a unicorn. Bubbles revealed their forlorn conversation: But Im prehistoric, quipped the dinosaur, while the unicorn replied, And Im mythological. The inside simply read: We can work it out.

If the dinosaurunicorn romance did work out, their offspring would look very much like a rhinoceros. In fact, the rhinoceros has long been associated with these two creatures from the prehistoric and mythic past.

UNICORNS

Travelling through the region of what is now Sumatra in the thirteenth century, Marco Polo (12541324) reported: There are wild elephants in the country and numerous unicorns which are very nearly as big. He described the unicorn as having the feet of an elephant, the head of a wild boar, and hair like a buffalo. The horn, he wrote, is placed in the centre of the forehead and is black and very thick. It is a very ugly beast to look at, Polo continued, and is not at all like the one our stories say is caught in the lap of a virgin. In fact, it is altogether different.