The Bridge at Andau is a work of historical fiction. Apart from the well-known actual people, events, and locales that figure in the narrative, all names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to current events or locales, or to living persons, is entirely coincidental.

2014 Dial Press Trade Paperback Edition

Copyright 1957 by James Michener

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Dial Press Trade Paperbacks, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

D IAL P RESS and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Random House LLC, in 1957.

eBook ISBN 978-0-8041-5148-1

www.dialpress.com

v3.1

Contents

Foreword

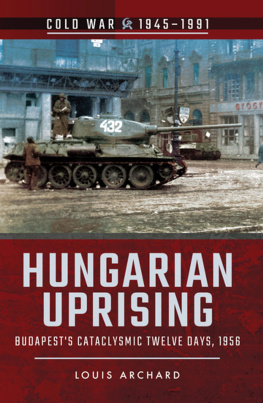

A t dawn, on November 4, 1956, Russian communism showed its true character to the world. With a ferocity and barbarism unmatched in recent history, it moved its brutal tanks against a defenseless population seeking escape from the terrors of communism, and destroyed it.

A city whose only offense was that it sought a decent life was shot to pieces. Dedicated Hungarian communists who had deviated slightly from the true Russian line were shot down ruthlessly and hunted from house to house. Even workers, on whom communism is supposed to be built, were rounded up like animals and shipped in sealed boxcars to the USSR. A satellite country which had dared to question Russian domination was annihilated.

After what the Russians did to Hungary, after their destruction of a magnificent city, and after their treatment of fellow communists, the world need no longer have even the slimmest doubt as to what Russias intentions are. Hungary has laid bare the great Russian lie.

In Hungary, Russia demonstrated that her program is simple. Infiltrate a target nation (as she did in Bulgaria and Rumania, for example); get immediate control of the police force (as she did in Czechoslovakia); initiate a terror which removes all intellectual and labor leadership (as she did in Latvia and Estonia); deport to Siberia troublesome people (as she did in Lithuania and Poland); and then destroy the nation completely if the least sign of independence shows itself. This final step in the Russian plan is what took place in Hungary.

From this point on it is difficult to imagine native-born communists in Italy or France or America trusting blindly that if they join the Russian orbit their fate will be any different. At the first invitation from some dissident communist group inside the nation, Russian tanks will ride in, destroy the capital city, terrorize the population, and deport to slave-labor camps in Central Asia most of the local communist leaders who organized the communist regime in the first place.

In this book I propose to tell the story of a terror so complete as to be deadening to the senses. I shall have to relate the details of a planned bestiality that is revolting to the human mind, but I do so in order to remind myself and free men everywhere that there is no hope for any nation or group that allows itself to be swept into the orbit of international communism. There can be only one outcome: terror and the loss of every freedom.

I propose also to tell the story of how thousands of Hungarians, satiated with terror, fled their homeland and sought refuge elsewhere. It is from their mass flight into Austria that this book takes its title, for it was at the insignificant bridge at Andau that many of them escaped to freedom.

That Budapest was destroyed by Russian tanks is tragic; but a greater tragedy had already occurred: the destruction of human decency. In the pages that follow, the people of Hungarymany of them communistswill relate what Russian communism really means.

A fifth printing of this book provides an opportunity to amend certain sections, for although few errors were found in the first edition, even those should be corrected.

I originally wrote that Hungarian names could be given in either orderImre Nagy or Nagy Imreand my notebooks were filled with examples proving that while talking with me, at least, Hungarians used the two forms indiscriminately. But I was wrong when I concluded that they followed the same practice at home. Several reviewers pointed out that in Hungary names are always given in what Americans would term reverse order: Nagy Imre. Why did my notes prove otherwise? Because the refugees, wanting to help me, tried at first to give their names in western order, reverting to the natural Hungarian style as they became involved in the depressing narratives they were sharing with me.

More importantly, it is now possible to extend my remarks concerning Americas role in the Hungarian revolution and her subsequent acceptance of its refugees. Four separate developments warrant comment.

First, I left the Hungarian border just as Vice-President Nixon departed for Washington with plans to speed up American acceptance of refugees. I was therefore not in a position to report upon the good his mission was to accomplish.

Second, protests like that of the New York Times concerning conditions during the first days at Camp Kilmer achieved their purpose, and the camp was quickly transformed into the warm, decent operation it should have been in the first place.

Third, while I was writing my report, new studies of Radio Free Europes role were completed and its function in the revolution was further clarified.

Fourth, and most important of all, it was only after I had completed my manuscript that America seriously considered, debated and adopted the Eisenhower Doctrine, which in effect warns that insofar as one section of the world is concerned, no new Hungary will be tolerated. This statement of American determination fills some of the policy hiatus I spoke of and forms, I believe, one of the major outcomes of the Hungarian revolution.

Several critics regretted that some of the characters through whom I told the story of the great Hungarian uprising were composites. They correctly pointed out that this dampened the force of the narrative. I agree. But it was not I who chose to use composites. It was my Hungarian narrators, who said simply, If the secret police identify me in any way, they will kill my mother and father. A writer thinks twice before betraying an identity in such circumstances, even though by using masked composites he does somewhat diminish the impact of his story.

Finally, one critic spoke harshly of my faith that the seeds of the Hungarian revolution will mature in other soil. He pointed out that so far this has not happened. He is correct. And it may not happen within a year, or three years, or even before both my critic and I are dead.

But I will stand by my statement. Somewhere within the Soviet hegemony the seeds of this Hungarian revolution will mature and grow into a profound struggle for human freedom. In the long sweep of mans history, three months are simply not enough time in which to detect significant movements.

Therefore I not only repeat what I said originally; I wish to intensify it. I am absolutely convinced that the yearning for freedom which motivated Hungarians will operate elsewhere within the Soviet orbit with results that we cannot now foresee. It would be inconceivable for me to conclude otherwise.