First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

PEN AND SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Louis Archard, 2018

ISBN 978 1 52670 802 1

eISBN 978 1 52670 804 5

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52670 803 8

The right of Louis Archard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to hear from them.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

email:

website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

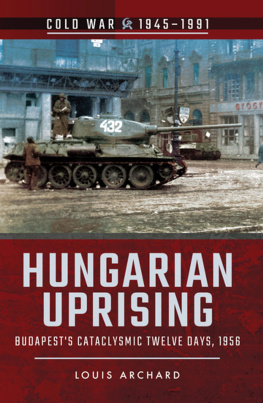

An altered road sign warns of tanks in Budapests Szentkirlyi Street. (Fortepan: Pesti Src)

Talpra Magyar, h a haza!

Itt az id, most vagy soha!

Rabok legynk vagy szabadok?

On your feet, Magyar, the homeland calls!

The time is here, now or never!

Shall we be slaves or free?

Sndor Petdwwfi, National Song

AUTHORS NOTE

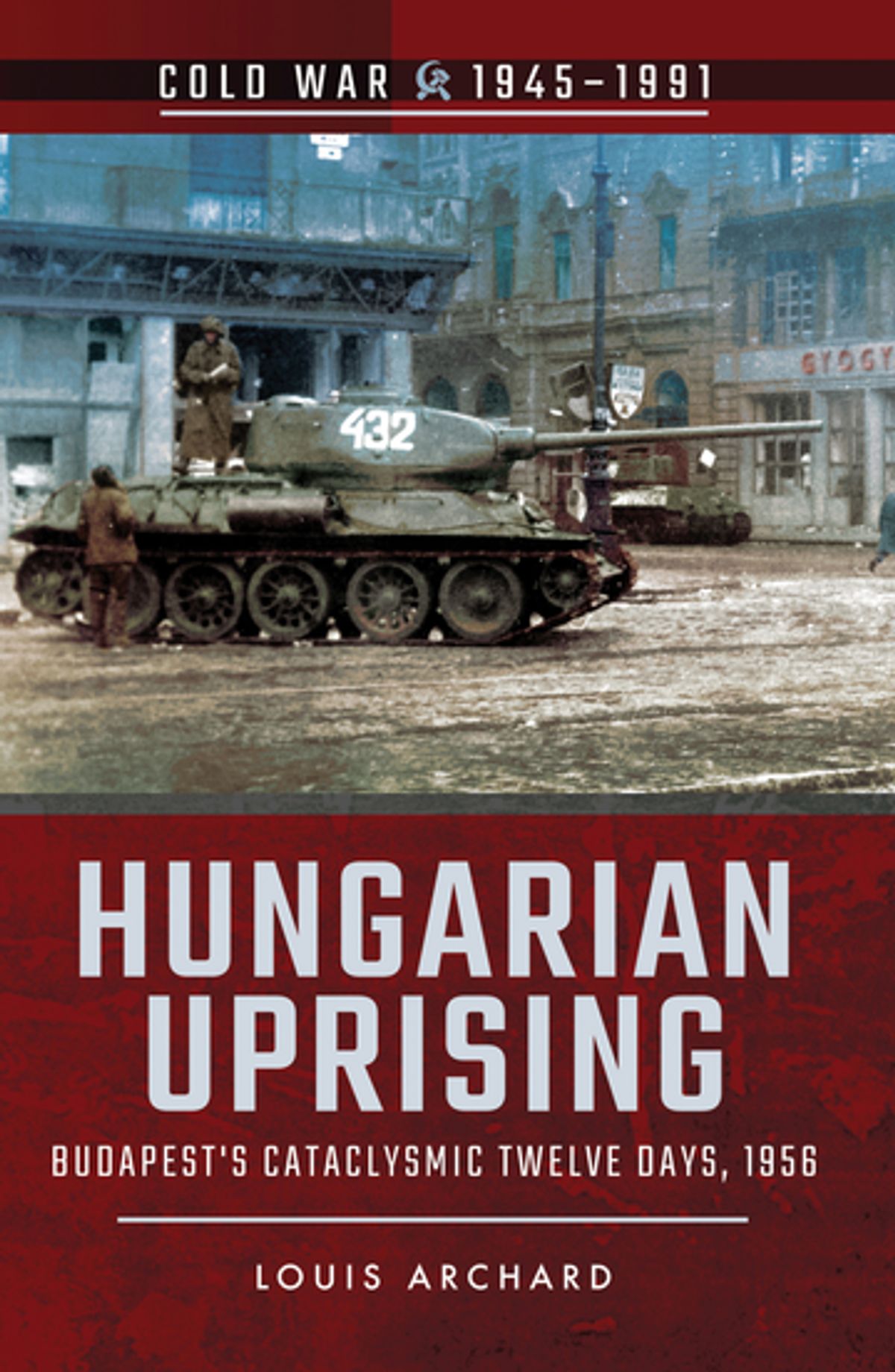

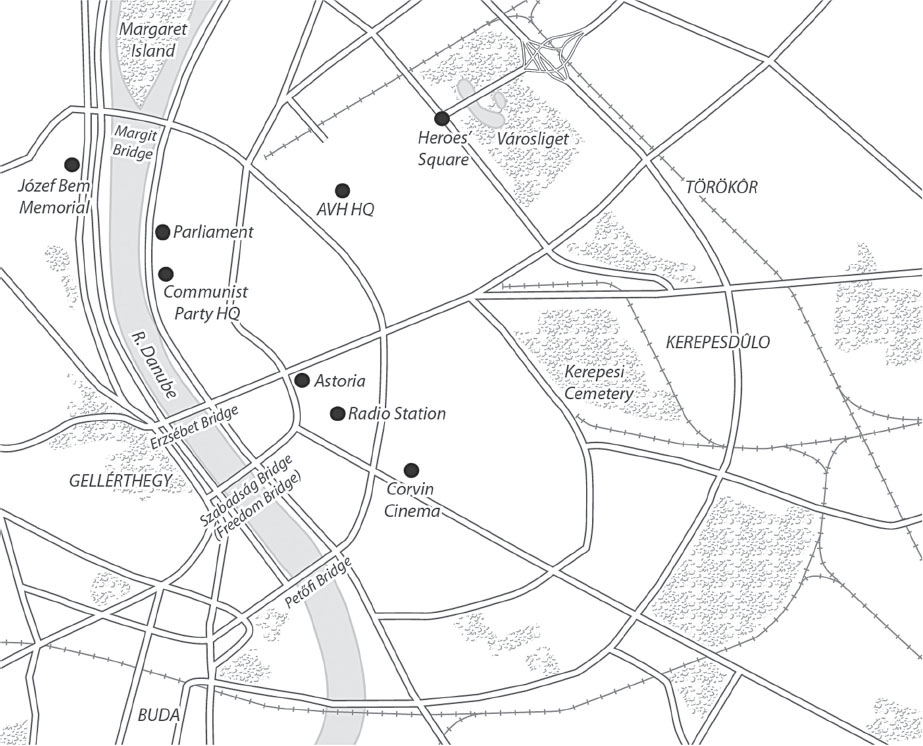

I visited Budapest in the autumn of 2007 nearly ten years ago at the time of writing and was very taken with it. I enjoyed the coffees and elaborate cakes served in the citys elegant coffee houses, appreciated as a novelty riding in the citys subway cars (because I was told that they had come second-hand from the Moscow Metro) and the beauty of the earliest part of the network (Budapest has the second oldest underground railway system in the world, after London) and generally soaked up the historic atmosphere. But I also noticed that many of the buildings in the city centre were still pockmarked with bullet holes and other damage and I soon guessed that this must be a relic of the 1956 uprising against the Soviets that had been focused in the Hungarian capital.

The Hungarian Uprising was a key point during the Cold War, one of those moments when the Cold War became hot. Khrushchevs decision to use military force to suppress the uprising once and for all demonstrated Soviet determination to preserve the sphere of influence that the USSR had established in Eastern Europe in the years immediately following the Second World War. That Soviet determination is what would turn the uprising into a tragedy, although it is difficult not to feel the exhilaration of the insurgents as at first they succeed beyond their wildest dreams. President Eisenhowers decision not to intervene in Hungary demonstrated that the Western powers were not willing to risk an open conflict with the Soviet Union, despite American rhetoric about rolling back communism and liberating the peoples of Eastern Europe.

But there is so much more to the story of the Hungarian Uprising than the superpower politics, fascinating though that can be. This was an organic revolution, driven by a sense that people had simply had enough. Looking at the account of the protests in Budapest on 23 October 1956, and at the student mass meeting the night before that had arranged it, it is striking that decisions that would later turn out to be crucial seem to have been taken as a result of interventions by people whose names went unrecorded. The Sixteen Points, the manifesto of the uprising, was drafted effectively by committee, a committee whose names have also gone unrecorded.

Although leaders did later emerge, no one of them was able to dominate the others. Even Imre Nagy, whose name is perhaps the most famous of the 1956 revolutionaries, often seems to have been scrambling to catch up with what was happening on the streets and struggled at first to understand the nature of what he was trying to lead. Its easy to feel sympathy for Imre Nagy, clearly a decent man trying to do his best under very difficult circumstances. However, although the uprising is the not the most controversial subject in Hungarian history (an honour that goes to the Treaty of Trianon, the settlement between the Allies and what had been the Hapsburg Empire at the end of the First World War), it is still a sensitive and controversial subject in Hungary itself and there are many interpretations of Imre Nagy and the decisions that he took.