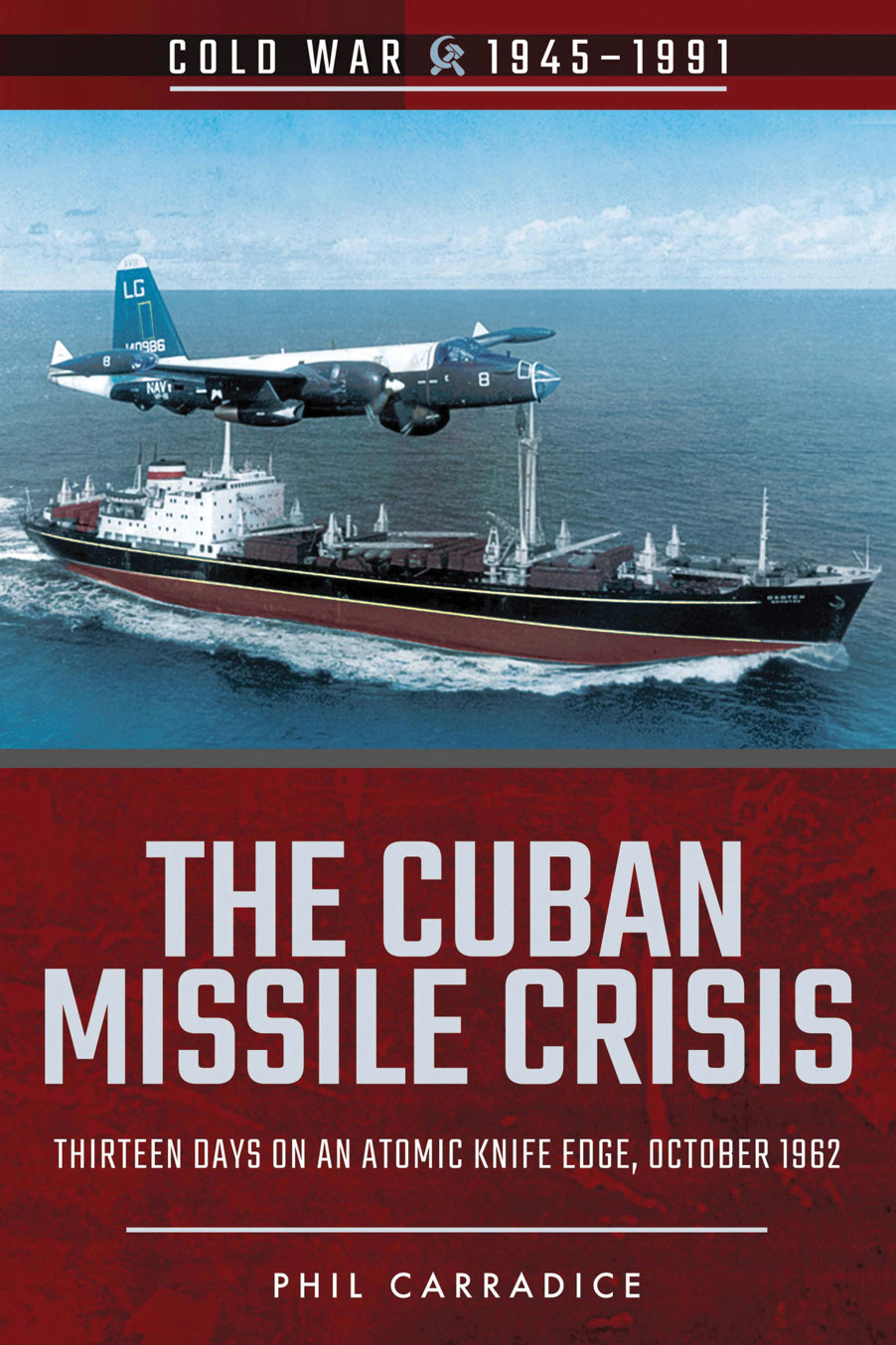

THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS

THIRTEEN DAYS ON AN ATOMIC KNIFE EDGE OCTOBER 1962

PHIL CARRADICE

For my Trudy, inspirational as ever, even if you did not live to see it completed.

This ones for you, kid.

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PEN AND SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Phil Carradice, 2017

ISBN 978 1 52670 806 9

eISBN 978 1 52670 808 3

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52670 807 6

The right of Phil Carradice to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to hear from them.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

email: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

On the face of it, readers could be excused for asking themselves why we need yet another book on the Cuban Missile Crisis. There are already enough of them to fill a shelf in any library. The answer is simple. Yes, this is a book about the infamous crisis of 1962 when the world came closer to extinguishing itself than ever before. But this one, I believe, is different.

To start with it was written because the publisher asked for it. That is not as crass or as glib as it sounds. The book is part of a series about the Cold War, and no account of that strange and delicately poised period would be complete without a look at the gravest moment in human history. The book fits into a sequence that, like an arch of bricks, would come crashing down if the crucial capstone happened to be missing.

There can never be too much written about a seminal event like the Cuban Missile Crisis. The only purpose behind any study of history is to learn from our mistakes and our successes. As Rudyard Kipling once said, if history was taught as a series of stories rather than a litany of dates and theories, we would all remember it much better. And not make the same mistakes again.

In keeping with that idea, this book is presented like a story, complete with characters, major and minor, each with agendas and parts to play. The story of the missile crisis is compelling and fascinating, with a plot that continually twists and turns. The exotic blends easily with the banal and the threat of destruction hangs over everything like a winter cloud.

I have never claimed to be a historian, but I do purport to be a story teller and what better for any story teller than a tale that, in its raw form, already exists.

The three vital ingredients of all stories are here, essentials that are as important to the written word as blood and oxygen are to the human body. They are the three Ps: place, people and problem. Without them, all stories will fail, but when they combine they create a tale that is utterly, compellingly beguiling.

People or characters create reader interest and here you have as wide a range as it is possible to find. The nave young man who comes of age in a rites of passage experience that can hardly be bettered, the hard-bitten politician whose bullying public persona hides an inner sensitivity that will, ultimately, destroy him, and the fanatical revolutionary who will stop at nothing to guarantee the safety of his country and his own place in history. They are, to misquote many a paperback blurb, all here.

The ability to hold the readers attention is an essential skill for any writer. I have always believed that, ever since my old history teacher, after reading one of my long and undoubtedly tedious essays on the religious settlement of Tudor England, casually tossed me a copy of Garret Mattinglys The Defeat of the Spanish Armada and suggested that I use it as my Bible.

If you want to be a writer, he declared, write like that.

Mattinglys book, I discovered, was pure history, but it read like a novel. I have tried, in my own way, to follow his example ever since.

An American newspaper cartoon succinctly showing the way the world thought about the Cuban Missile Crisis a showdown between Kennedy and Khrushchev.

There still remains the need to be accurate, to be historically correct. This book may, hopefully, read like a novel, but dates, speeches, and the all-important facts are presented as and when they occurred. There is no falsification or changing of the plot in order to heighten tension, the story does that on its own.

Interpretation? That you will find. Putting your own slant on events and people, as well as giving an opinion on policy, has always been the preserve of the historian or writer.

Lastly, it is inevitable that people involved in the crisis, either as main players or as peripheral characters, are dying. The Kennedys, Castro, Che and Khrushchev have already gone. Others will follow them in the years ahead. It will not be long before the story of the crisis is relegated from the memory of mankind to the cold, dry pages of history text books.

Nobody much below the age of 65 will have a genuine first-hand memory of the events. What they will have are stories told to them by parents, teachers, even by newspapers, which are now happy to relive it all. That is one reason why there is a chapter in the book devoted to the recollections of ordinary people who lived through the crisis, as children, as members of the armed forces, as students, and as ordinary working men and women. It is as important to record their views as it is to set down the ideas and thoughts of the big players.

All good stories need a hero and a villain, and one final way in which this book is different, is in its choice of both in the guise of one man. The tragic and ultimately doomed figure of Nikita Khrushchev strides like a modern-day King Lear across the stage where he is both hero and villain. He wears the ambiguity well, towering like a colossus over the chaos that he has created. He, not the Kennedy brothers, not Castro or Che, is the man who makes the story.