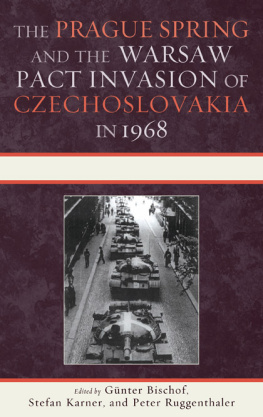

PRAGUE SPRING

WARSAW PACT INVASION, 1968

PHIL CARRADICE

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

PEN AND SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Phil Carradice, 2019

ISBN 978 1 52675 700 5

eISBN 978 1 52675 701 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52675 702 9

The right of Phil Carradice to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to hear from them.

Maps by George Anderson

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

email:

website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

Pen and Sword Books

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

email:

www.penandswordbooks.com

INTRODUCTION

The Prague Spring of 1968 was one of the great people-induced movements of the twentieth century. It was not just a local phenomenon, confined simply to Czechoslovakia: millions of people across the world were influenced by what was going on in Prague. Even from a distance they could see and rejoice in an oppressed people finally discovering a toehold on the island of democracy.

The crushing of that democracy, that freedom, followed as surely as summer follows spring. And it was equally as significant. The Prague Spring made a huge impact in Czechoslovakia and in the world but the Soviet invasionthere is no other way to describe itbrought a degree of realism to a people who had basked a little too easily in the golden glow of a make-believe innocence.

The Soviet tanks brought that world to a sudden and violent halt. Reality hit home with a brutal power that surprised everyone. There were no exceptions or allowances to be made. After August 1968 the rule was simple: obey or suffer the consequences.

Thousands of men and women, most of them under the age of 25, flocked to the streets of Prague to protest against Soviet oppression. They shouted and chanted, they fought and hurled rocks, they set fire to tanks and armoured cars. Many died trying to make their protest. Having tasted the Prague Spring and then lost it, the people of Czechoslovakia were clear about their objectives: they wanted it back.

The Prague Spring may well have been a movement of the people, a more intense version of the hippie culture that had recently swept America, but it would still not have happened without the influence of one man, Alexander Dubcek. It is impossible, now, to look at the Czechoslovakian events of 1968 without the figure of Dubcek striding into view.

A bronze bust of Alexandra Dubcek, by sculptor Ludmila Cvengrosova. (Peter Zelizk)

Soviet troops in Budapest, 1945. It would be some forty-five years before they left. (Fortepan)

Dubcek was a colossus, a mighty figure on the world stage, a man of vision and belief. He was courageous and dedicated and no account of the Prague Spring and its consequences would be complete without looking at his successes, and his failures. It is impossible to separate him from the events of that yearand of the ones that followed when he lost power but never lost or forgot his ability to hope.

Dubcek and the Prague Spring are, ultimately, one and the same thing. So while it is right to acknowledge the bravery of those who joined the demonstrations and the protest marches or the sheer dedication of men like Jan Palach who made the ultimate sacrifice, the courage of Alexander Dubcek should never be forgotten.

When one man refuses to bow down and surrender to the advances of a bully it is a moment to be savoured. We would all hope for the same degree of courage but fear and doubt must inevitably take their toll. Alexander Dubcek did not fear and he did not doubt, not even for a moment.

1. END OF THE SUMMER OF LOVE

It was January 1968 and the winds of change were already blowing. Gone was the previous year: 1967 with its magical summer of love was no more. That was the past, a period consigned to memory along with the ashes of New Years Eve and the faint concern that maybe the future might not be so remarkable or as bright as everyone imagined.

In the minds of many, the previous twelve months had been memorable although, even now, there still remains the disturbing old adage that if people can remember the happenings of the year, really remember them, then they werent actually there. Perhaps that is true. Most people werent therewherever there might be.

When viewed dispassionately, the year 1967 had been little more than an extension to the phenomenal eruption of what was immediately classed as the hippie culture. It was a period of flared jeans, tie-dyed T-shirts, peace and love for all. For many observers the lasting image of the year was of a protesting student placing a flower into the muzzle of a rifle belonging to one of Americas National Guard. It was a time when, for the young at least, it seemed as if the world was changing for ever.

In reality, that change was limited in scope and location. Everyone believed they could be a part of the cultural and social revolution that appeared to be engulfing the whole worldeven if they ventured no further than the local coffee bar or the church hop on a Saturday nightbut it was a false dogma that empowered only the bare minimum of people.

Memory says it was a time of free love, free expression and free dreams. That, certainly, was what the media fed to the thousands of credulous young adults who waited, in awe, for the latest Rolling Stones or Byrds record and tried to follow George Harrisons finger movements on the fret board of his sitar. Everybody could be a part of it, the papers and magazines screamed at you, as long as you had the courage to seize your chance when it appeared.

It was actually all a wonderful deception. The summer of love was, in reality, confined to the Height-Ashbury district of San Francisco and while in many parts of the world there were those who tried to emulate the bare-footed, bare breasted antics of the in crowd, for most people 1967 had been no more than just another year. Jobs, education, settled relationships were the lot of most citizens. The summer of love was simply something to read about in the newspapers or watch on TV.