Conversations with Gorbachev

MIKHAIL GORBACHEVZDENK MLYN

Conversations

with

Gorbachev

ON PERESTROIKA, THE PRAGUE SPRING, AND THE CROSSROADS OF SOCIALISM

Translated by George Shriver

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2002 Mikhail Gorbachev

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52927-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gorbachev, Mikhail Sergeevich,1931-Conversations with Gorbachev : on perestroika, the Prague Spring, and the crossroads of socialism/Mikhail Gorbachev, Zdenek Mlynar.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-231-11864-3 (cl.)

1. Gorbachev, Mikhail Sergeevich, 1931Interviews. 2. Mlyn, ZdenkInterviews. 3. Perestroka. 4. CzechoslovakiaHistoryIntervention, 1968. 5. Socialism. I. Mlynr, Zdenek. II. Title.

DK290.3.G67 A5 2002

943.704dc2I

2001058228

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

PUBLISHERS NOTE

Although a Russian edition of this book was planned, as of this edition, no Russian edition exists. An edition was published in Czech under the title Reformatory nebyvaji stastni. Dialog o perestrojce, Prazskem jaru a socialismu. It was published by the Victoria publishing house, Prague, in 1995.

CONTENTS

by Arckie Brown

This book, based on conversations between Mikhail Gorbachev and the late Zdenk Mlyn, is an important historical document. It provides insights into the evolution of the political ideas of two highly intelligent peoplefrom dogmatic Communism to Communist reformism (or revisionism) to a social democratic understanding of socialism. When one of those concerned played the decisive role in the pluralization of Soviet politics and in the ending of Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, that gives an especial significance to how his way of looking at the world gradually evolved.

There are critics of Gorbachev who have denied that his ideas shifted fundamentally on the grounds that he continued to express a commitment to socialism. Such criticism represents an all too common failure to understand the gulf separating the socialism of orthodox Communism, based on Marxist-Leninist ideology and the monopoly of power of a highly disciplined ruling party, from the socialism espoused by West European mass parties that throughout the greater part of the twentieth century competed, generally successfully, with Communists for the support of working-class and many middle-class voters.

A misunderstanding of social democracy is widespread both in Russia and the United States, for neither countryunlike the majority of European (especially West European) stateshas had a successful social democratic movement or party. During the perestroika period the late Alec Nove drew attention to the growing number of ideologues of the market economy to be found in Russia who had taken to denouncing the West European welfare state in the crudest Chicago terms and who seem to see not only Swedes but even the West German social democrats as dangerous lefties who desire to travel the road to serfdom slowly. In reality, the attachment of West European social democrats to liberty stands up to scrutiny at least as well as the noisy rhetorical support for freedom of their conservative rivals.

Socialists of a social democratic persuasion can find good grounds for arguing that they led the way in making freedoms more meaningful for the majority of the population, while attempting, with some success, to combine their attachment to political liberty with a concern for social justice. As young and enthusiastic Communists, Mikhail Gorbachev and Zdenk Mlyn discounted the crucial importance of institutionalizing political freedoms, but they were genuine seekers after social justice. Their lifetimes experience taught them that without democracy, some citizens would still be infinitely more equal than others and social justice under Communism would be thin gruel compared with what was on offer in the welfare states established in the social democratic countries of Northern and Western Europe.

While rejecting the view that almost everything could be left to the market, they nevertheless came to believe that market economies were more efficient than the Soviet-style command economy and that they were capable of producing significantly higher levels of social welfare. Gorbachev, born into a peasant family in southern Russia long after a Communist system had been established in the Soviet Union, and knowing no other socioeconomic order until well into his adulthood, came to see (as he puts it in the pages that follow) that the system held everyone in its grip, stifling initiative. In order to protect itself, it suppressed both freedom of thought and any kind of searching or exploration. In addition to its dire political consequences, this held back economic development, except in certain selected areas where the nature of the centralized economy meant that disproportionately great resources could be directed. That applied, above all, to military industry and, for some years, to the space program.

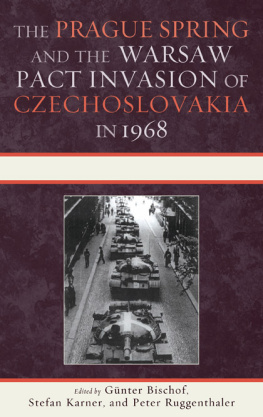

In seeking to reform the Communist system, both of these politicians had to come to terms with unintended, as well as intended, consequences of their actions. Zdenk Mlyn, the leading theoretician of the Prague Spring, had to face the fact that as a direct result of the attempted reform of the political and economic system in Czechoslo vakia his country became for a period of two decades still more politically oppressive than it had been in the years immediately preceding the radical reforms of 1968. The Soviet armed intervention, which put an end to the Prague Spring, not only led in 1977 to Mlyns exile from his homeland (after he had become an organizer and a signatory of the oppositional Charter 77), but also had earlier brought to power an unscrupulous political leadership far more responsive to Moscow than to their own people.

For Mikhail Gorbachev the unintended consequences of introducing transformative change of the Soviet polity were even more dramatic. Along with his great achievements, not the least of which were leaving his country freer than it had ever been and playing the key role in ending the Cold War, were such unlooked-for results as the breakup of the Soviet Union. The dismantling of the Soviet system was something that Gorbachev came to believe, in the course of his leadership of the Communist Party, was both desirable and necessary. Had he not used the powers of the General Secretaryship of the Soviet Communist Party, to effect thatskillfully, peacefully, and by evolutionary meansit is certain that Communism would not have ended when it did and more than likely that it would still be the ideology in power in Moscow. In contrast with change of the system, the breakup of the Soviet state into fifteen piecesthe Soviet successor stateswas entirely contrary to his intentions.

In historical perspective, though, it should be abundantly clear that the positive results of Gorbachevs radical reforms greatly outweigh the negative. Many observers, indeed, see the existence of fifteen states, rather than one, on the territory of the former Soviet Union also as a plus, though, of the successor states, only the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are well on the way to establishing consolidated democracies. Russia, and one or two others, have hybrid systemsa mixture of arbitrariness and democracyand a majority of these new members of the United Nations have unambiguously authoritarian regimes. For those who value democracy and the rule of law above the ambiguous right of every nation (however defined) to have its own state (a process opening up the prospect of almost infinite regress), it remains far from clear that the complete breakup of the Soviet state should be welcomed. The independence of the Baltic states, whose forcible incorporation into the USSR in 1940 had never been accepted as legitimate either by the indigenous inhabitants or by the West, was a democratic necessity. It is highly doubtful, however, that the complete disintegration of the Soviet Union has furthered the cause of democracy as distinct from that of self-serving and corrupt national elites. Survey research in post-Soviet Russia shows conclusively that a majority of