SOCIALISM

Michael Newman

New York / London

www.sterlingpublishing.com

STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016

Published by arrangement with Oxford University Press, Inc.

2005 by Michael Newman

Illustrated edition published in 2010 by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. Additional text 2010 Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Distributed in Canada by Sterling Publishing c/o Canadian Manda Group, 165 Dufferin Street Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6K 3H6

Book design: Faceout Studio

Please see picture credits on page 207 for image copyright information.

Printed in China

All rights reserved

Sterling ISBN 978-1-4027-7537-6

For information about custom editions, special sales, premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales Department at 800-805-5489 or .

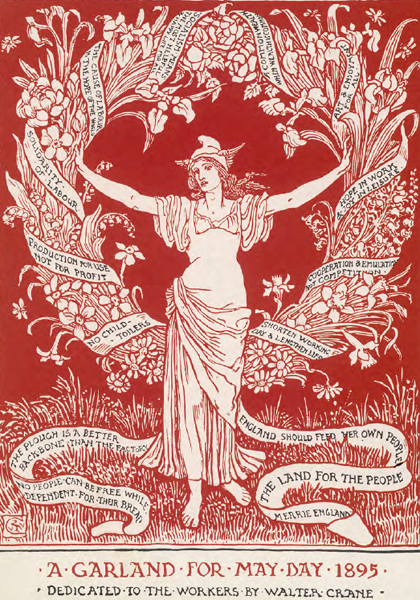

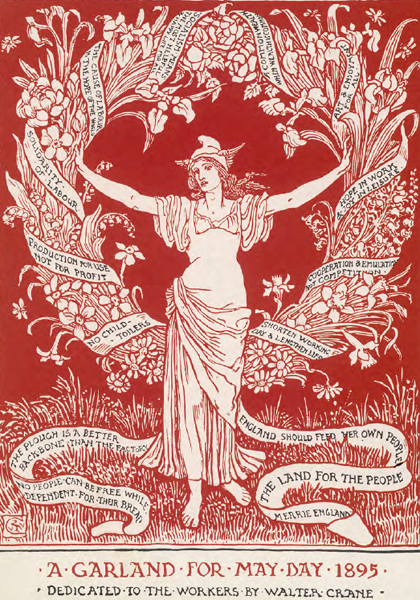

Frontispiece: The English artist Walter Crane (18451915) was not only a prominent illustrator of childrens books, he was a committed socialist as well. This illustration was published in the magazine Clarion in 1895 to commemorate May Day, the international workers holiday.

CONTENTS

Writing a very short book on a vast subject has been a great challenge, and I am grateful to all those at Oxford University Press who have given me this opportunity. In particular, I would like to thank Marsha Filion for her helpful suggestions and Alyson Lacewing for her skilful copyediting. I very much appreciate the comments on earlier drafts by Kate Soper, Richard Kuper, Marjorie Mayo, my daughter Kate, and an anonymous referee. I am also conscious of many people who have influenced my thinking about socialism, particularly the late Peter Seltman, an inspiring colleague to whose memory I would like to dedicate this work. But as always, I owe most of all to Ines for her constant encouragement and support, our ongoing dialogue on the subject matter, and her cogent criticisms.

My aims have been to provide an accessible introduction while simultaneously providing food for thought on a controversial topic. I hope not to cause those who disagree with my interpretation too much indigestion!

This gathering of socialists took place in New York Citys Union Square on May 1, 1912.

IN 1867 KARL MARX ended the first volume of his monumental work Das Kapital on a triumphant note. A point would be reached, he argued, when the capitalist system would burst asunder and at this stage:

The knell of capitalist private property sounds. The expropriators are expropriated.

For more than a hundred years many socialists believed, and many of their opponents feared, that Marx had been right: capitalism was doomed and would be replaced by socialism. How things have changed! In recent years, and particularly since the collapse of the Soviet bloc between 1989 and 1991, a dramatic reversal has taken place. It is now capitalism that is triumphant, and many regard socialism as an historical relic which will probably die out during the course of the current century. I do not share this belief, and the final chapter of this book seeks to demonstrate the continuing and contemporary relevance of socialism. But whether or not the reader will agree with this conclusion, I hope that the book will at least provide clarification and discussion as a basis for judgment.

The first, and crucial, question is: what is socialism? Those who attack or defend socialism often take its meaning as self-evident. Thus the opponents of all forms of socialism have been keen to dismiss the whole idea by equating it with its most repellent manifestationsparticularly the Stalinist dictatorship in the Soviet Union from the late 1920s until 1953. Similarly, its proponents have tended to identify socialism with the particular form that they have favored. Lenin therefore once defined it as soviet power plus electrification, while a British politician, Herbert Morrison, argued that socialism was what a Labour government does. Yet socialism has taken far too many forms to be constricted in these ways. Indeed, some have viewed it primarily as a set of values and theories and have denied that the policies of any state or political party have had any relevance for the evaluation of socialism as a doctrine. This purist position lies at the other extreme from that of Lenin and Morrison and is equally unhelpful. In fact, socialism has been both centralist and local; organized from above and built from below; visionary and pragmatic; revolutionary and reformist; anti-state and statist; internationalist and nationalist; harnessed to political parties and shunning them; an outgrowth of trade unionism and independent of it; a feature of rich industrialized countries and poor peasant-based communities; sexist and feminist; committed to growth and ecological.

One way of discussing so diverse a phenomenon is to claim that all forms of socialism share some fundamental characteristic, or essence, by which the doctrine as a whole may be defined. Certainly, this would simplify analysis, but this essentialist approach normally degenerates into rather dogmatic assertions about the nature of true socialism and becomes a weapon to use against the heretics. However, there are equal dangers in defining socialism so broadly that the subject cannot be analyzed meaningfully. This book seeks to overcome these contradictory dangers by taking the following minimal definitions of socialism as guidelines.

In my view, the most fundamental characteristic of socialism is its commitment to the creation of an egalitarian society. Socialists may not have agreed about the extent to which inequality can be eradicated or the means by which change can be effected, but no socialist would defend the current inequalities of wealth and power. In particular, socialists have maintained that, under capitalism, vast privileges and opportunities are derived from the hereditary ownership of capital and wealth at one end of the social scale, while a cycle of deprivation limits opportunities and influence at the other end. To varying extents, all socialists have therefore challenged the property relationships that are fundamental to capitalism, and have aspired to establish a society in which everyone has the possibility to seek fulfillment without facing barriers based on structural inequalities.

A second, and closely related, common feature of socialism has been a belief in the possibility of constructing an alternative egalitarian system based on the values of solidarity and cooperation. But this in turn has depended on a third characteristic: a relatively optimistic view of human beings and their ability to cooperate with one another. The extent, both of the optimism and its necessity for the construction of a new society, varies considerably. For those who believe in the possibility of establishing self-governing communities without hierarchy or law, the optimistic conception of human nature is essential. For others who have favored hierarchical parties and states, such optimism could be more limited. It is also no doubt true that, in the world after Nazism and Stalinism, the optimism of some earlier thinkers has been tempered by harsh realities. Nevertheless, socialists have always rejected views that stress individual self-interest and competition as the sole motivating factors of human behavior in all societies at all times. They have regarded this perspective as the product of a particular kind of society, rather than as an ineradicable fact about human beings.