Contents

For as he thinketh in his heart, so is he.

Proverbs 23:7

Look, Mommy, that bus says, Make a Wish. Whats your wish?

My wish is for your happiness, health, and safety your whole life, Gus. Whats your wish?

My wish is to live in New York City my whole life, and to be a really friendly guy.

But not too friendly, right?

Whats too friendly?

These days, its considered politically incorrect to call a person autistic. If you do, you are defining that person entirely by his or her disability. Instead, youre supposed to use person-first language: a man with autism, a woman with autism.

I understand the thinking here. Its like calling a person who has dwarfism a dwarf; is short stature the one thing that defines him or her as a human being? But as a tiny friend said to me recently, Oh, for Gods sakes, just call me a dwarf. Its the first thing you see, and I know its not the only thing about me thats interesting.

Person with autism also suggests that autism is something bad that one needs distance from. Youd never say a person with left-handedness or a person with Jewishness. Then again, you might say a person with cancer.

Autism does not entirely define my son, but it informs so much about him and our life together. Saying autism is something you are with suggests its something you carry around and can drop at will, like a purse. Theres also something about this pseudo delicacy that is patronizing as hell. Not that Im against every carefully considered word for disability. I just want the words to be true. When you call autistic people neurodivergent, for example, you are not stretching for political correctness; you are accurately describing their condition.

(I am all for finding new language that is descriptive and fun and to the point. If you want to ask delicately if someone is autistic, how about asking if he or she is a FOTFriend of Trains? I mean, if there can be Friends of Dorothy... )

Theres yet another reason I use the term autistic freely here: you try writing an entire book using the phrase person with autism over and over again. Its clunky. So I will sometimes refer to men and women here as autistic. I will also defer to the masculine pronoun when I am talking about people in generalities, because I learned that it was correct to do this sometime back when dinosaurs roamed the earth. I mention this because a friend just wrote an excellent book on parenting using the pronoun they instead of he or she, and she uses the term cisgender to refer to anyone who is well, cisgender, which is one of the at least fifty-eight gender options offered by Facebook, ranging from Agender to TwoSpirit. She did this at the insistence of her teenage daughter. Language needs to evolve, but not into something ugly and imprecise. I read her book simultaneously loving her parenting philosophy and wanting to punch her in the face.

But whatever her crimes against the English language, my friend consulted with her kids about their place in her book. I did not. This is both selfish and necessary. While Guss good-natured attitude about being my subject has always been, I will be a celebrity, Mommy, Henrys feelings change with his mood. At first, he was cavalier in a way guaranteed to irritate me: Oh, it doesnt matter, I never read what you write anyway. At that point there was talk about whether he would get a share of the profits, and a quick glance at his computers Google history revealed the phrase film option. Then, when it dawned on him that people he knows actually do read, he panicked a little. So writing about him became a negotiation, which sometimes he won and sometimes he lost. He was fine about being portrayed as a smart-ass bro. What he worried about was that I might reveal him to be the sweet, caring, wonderful soon-to-be man he really is. I only slipped a little.

There are many good, some great, books about autism (see Resources, page TK)about the science, the history, treatments. While this book touches on all these subjects, you will never see a review of it that begins, If you have to read one book about autism... This is not that One Book. It is a slice of life for one family, one kid. But I hope it seems sort of a slice of your life, too.

When I wrote the original story about Gus and Siri for the New York Times, Gus was twelve. Most of this book takes place when my sons are thirteen and fourteen. When the publisher tears the manuscript from my hands, they will be fifteen, then sixteen when it hits the remainder bin. Kids grow older, and I wanted this book to be accurate, so I would still be writing and changing it if my agent hadnt called me one day and said, For the love of God, just put a period on it.

So I did.

My kids and I are at the supermarket.

We need turkey and ham!

Gus tends to speak in exclamation points. A half pound! And... what, Mommy? Im stage-whispering directions, trying to keep the conversation focused on deli meats. Behind the counter, Otto politely slices and listens, occasionally interjecting questions. Were on track here.

And then... were not.

So! My daddy has been in London for ten days, and he comes back in four days, on Wednesday. He comes in to JFK Airport on American Airlines Flight 100, at Terminal Eight, Gus says, warming to the subject. What? Yes, Mom says thin slices. Also, coleslaw! Daddy will take the A train from Howard Beach to West 4th and then change to the B or D to BroadwayLafayette. Hell arrive at 77 Bleecker in the morning and then he and Mommy will do sex...

Suddenly Otto is interested. What?

You know, my daddy? The one who is old and has bad knees? He arrives at Terminal Eight at Kennedy Airport. But first he has to leave from London at Kings Cross, which goes to Heathrow, and the plane from Heathrow leaves out of

No, Gus, the other part, says Otto, smiling. What does Daddy do when he gets home?

Gus presses on with his explanation, ignoring the little detail his twin brother, Henry, whispered in his ear. Henry stands off to the side, smirking, while Gus continues with what really interests him: the stops on the A line from Howard Beach. I see the slightly alarmed looks on the faces of the people waiting in line. Is it the content of Guss chatter or the fact that he is hopping up and down while he delivers it? When hes happy and excited, which is much of the time, he hops. Im so used to it I barely notice. But in that moment I see our family the way the rest of the world sees us: the obnoxious teenager, pretending he doesnt know us; the crazy jumping bean, nattering on about the A train; the frazzled, fanny-pack-sporting mother, now part of an unappetizing visual of two ancients on a booty call.

Yet I want to turn to everyone in line and say, You should all be congratulating us. Several years ago, Hoppy over there would hardly have been talking at all, and whatever he said would have been incomprehensible. Sure, we have a few glitches to work out. But youre missing the point. My son is ordering ham. Score!

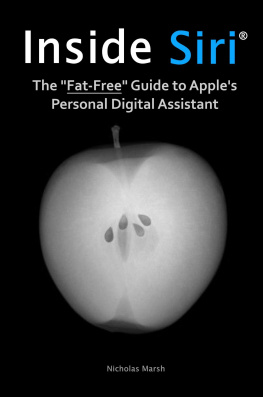

You may recognize Gus as my autistic son who recently enjoyed his fifteen minutes of fame. I wrote a story for the New York Times called To Siri, With Love, about his friendship with Siri, Apples intelligent personal assistant. It was a simple piece about how this amiable robot provides so much to my communication-impaired kid: not just information on arcane, sleep-inducing subjects (if youre not a herpetologist, Im guessing youre about as eager as I am to talk about red-eared slider turtles) but also lessons in etiquette, listening, and what most of us take for granted, the nuances of back-and-forth dialogue. The subject is close to my heartits my son, so how could it not be?but I thought the audience for this sort of thing was limited. Maybe Id get a few pats on the back from friends.