CONTENTS

FOR JOYCE

With the hope that saner times will prevail in the lives of

Jen & David, Margot & Joel, Erin & Jon,

Julia, Asher, Phoebe & Jake.

AUTHORS NOTE

Histories of the Cuban Missile Crisis have appeared in every decade since October 1962, and they have progressively uncovered more secrets and memories not only in the United States but also, at last, in Russia and Cuba. The revelations and ever more informed speculations have greatly enriched the tale and made it the most elaborately examined political episode of the past century. Yet paradoxically, all these studies have also exacerbated debate about the motivations of the Soviet and American leaders who produced, managed, and finally resolved the crisis.

I dare to add my own retelling of the tale from a distance of forty years because I have found in the growing literature much fascinating detail to enlarge my contemporary experience of the crisis and to confirm my understanding of its major elementswhy the crisis occurred, how it played out, and how close the world came to nuclear war.

I write with the memories of a reporter who covered the crisis as it unfolded, for The New York Times in Washington. I also write and reflect with the experience of covering the diplomacy and politics of John F. Kennedys Washington, Fidel Castros Havana, and Nikita S. Khrushchevs Moscow, experiences that entailed close observation of most of the principals in this story. And I have freely exploited the extensive library produced by the crisis: dozens of histories and memoirs, works of intense scholarship, and the oral testimony evoked at multiple reunions of some of the Soviet, American, and Cuban antagonists. That the record remains incomplete and at times contradictory should be neither surprising nor discouraging; human history cannot escape the complexity of human thought and deed.

The books and documents to which I am most indebted are listed in the bibliography. But gratitude and fairness require a special, upfront tribute to James G. Blight, David A. Welsh, and Bruce J. Allyn, who labored to arrange the reunions of crisis participants, to record and annotate their exchanges, and to wean important, albeit incomplete documentation from Cuban and former Soviet archives. Equally essential to any review of the crisis are the recordings of White House meetings made by President Kennedy and transcribed under the leadership of Timothy Naftali, Philip Zelikow, and Ernest May (with important supplementary corrections by Sheldon M. Stern, the former historian at the John F. Kennedy Library). Yet even that massive record requires the balance of once secret documents brought to light through the persistent work of the National Security Archive in Washington and of Timothy Naftali and Aleksandr Fursenko in Moscow. My interpretations at times differ from theirs, but their masonry of fact has left an indispensable foundation for all who follow.

M. F.

THE CRISIS IN MEMORY

F OR MOST AMERICANS WHO EXPERIENCED IT, OR RELIVED it in books and films, the Cuban Missile Crisis is a tale of nuclear chickenthe Cold War world recklessly flirting with suicide.

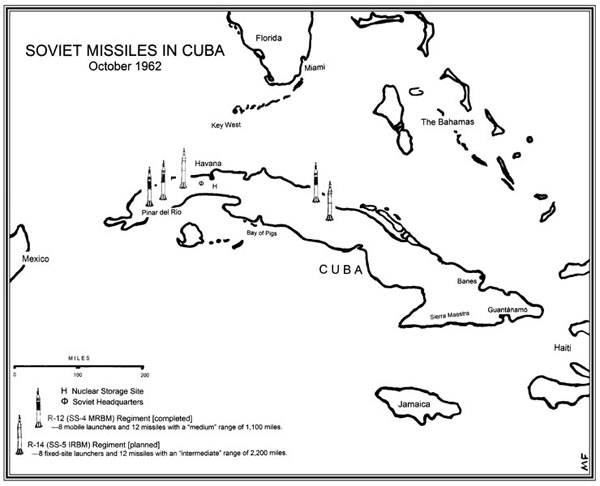

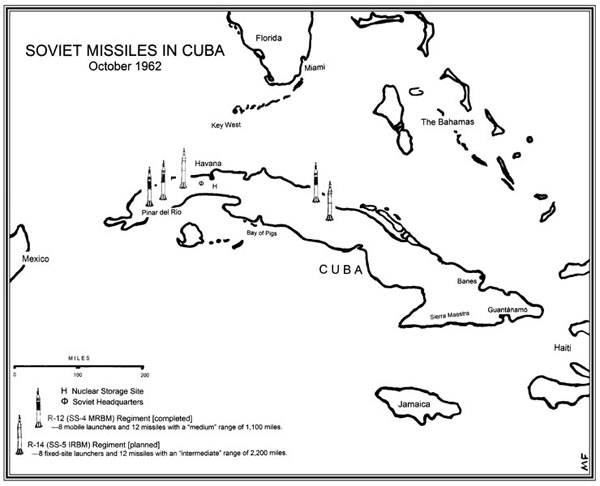

We remember a bellicose Soviet dictator, who had vowed to bury us, pointing his missiles at the American heartland from a Cuba turned hostile and communist.

We remember a glamorous president, standing desperately against the threat, risking World War III to get the missiles withdrawn.

We remember the Russians blinking on the brink, compelled to retreat by a naked display of American power, brilliantly deployed, unerringly managed.

The crisis was real enough, but for the most part, we remember it wrong.

No episode of the last century has been so elaborately documented, so often reenacted in print and on film, and so many times earnestly reexamined at extraordinary reunions of Russian, American, and Cuban veterans of the drama. As one of them, McGeorge Bundy, has observed, forests have been felled to print the reflections and conclusions of participants, observers and scholars of the crisis. And most recently, their views and recollections have been augmented by voluminous government records of the United States, some from old Soviet archives, and even a few from Cuban dossiers.

Yet over the decades, even the most attentive scholars and participants kept debating the main questions surrounding this sensational event. They failed to agree on why it happened, and they lacked the facts about how it really ended. And they have still not overcome the popular misconceptions about the motives and conduct of the two Cold War antagonistsNikita Khrushchev, the wily old peasant ruling the Soviet empire, and John F. Kennedy, the jaunty young president leading the Western democracies. Nor have the many histories overcome the temptation to enrich the drama with alarmist claims that these two supercharged men came within hours, even minutes, of igniting an all-out nuclear war.

The fear of war during the crisis week of October 2228, 1962, was palpable, in the Kremlin as in the White House. It was even greater among populations that could read uncensored accounts of the chilling, intimidating rhetoric with which Khrushchev and Kennedy bargained for concessions to resolve the crisis. Yet with all the information now available, it is clear that Khrushchev and Kennedy were effectively deterred by their fear of war and took great care to avoid even minor military clashes. In the end, both were ready to betray important allies, resist the counsel of chafing military commanders, and endure political humiliation to find a way out of the crisis. Their anxiety was real. But with the benefit of time and distance from the emotions of the Cold War, we can now see that their reciprocal alarm kept them well away from a nuclear showdown.

Time and distance also serve to illuminate the causes of the fateful events of 1962 that Americans call the Cuban Missile Crisis.

As I first sensed in reporting from Moscow at the height of Khrushchevs power, his pugnacity was born of a typically Russian insecurity. His most aggressive actions against the West tended to mask a deeply defensive purpose. The evidence now available, though still debated, shows that it was to offset a debilitating weakness, not to imperil America, that Khrushchev careered into the crisis.

And as I slowly learned in covering Kennedys Washington, the imperative of protecting himself politically inevitably shapes a presidents perception of the nations security. The cumulative record shows that Kennedys decision to challenge the Soviet missiles in Cuba was rooted in a need to prove himself, more even than in any threat posed by the missiles themselves. Yet in reporting the day-to-day events of the crisis, and reading the many Washington-centered accounts in later years, I never fully appreciated the extent of Kennedys statesmanlike restraint in steering his team to a diplomatic resolution. Though haunted by domestic critics, he nonetheless weighed every move with respect for his adversary and showed a decent regard for the opinions of other affected nations and the judgment of history.

Next page