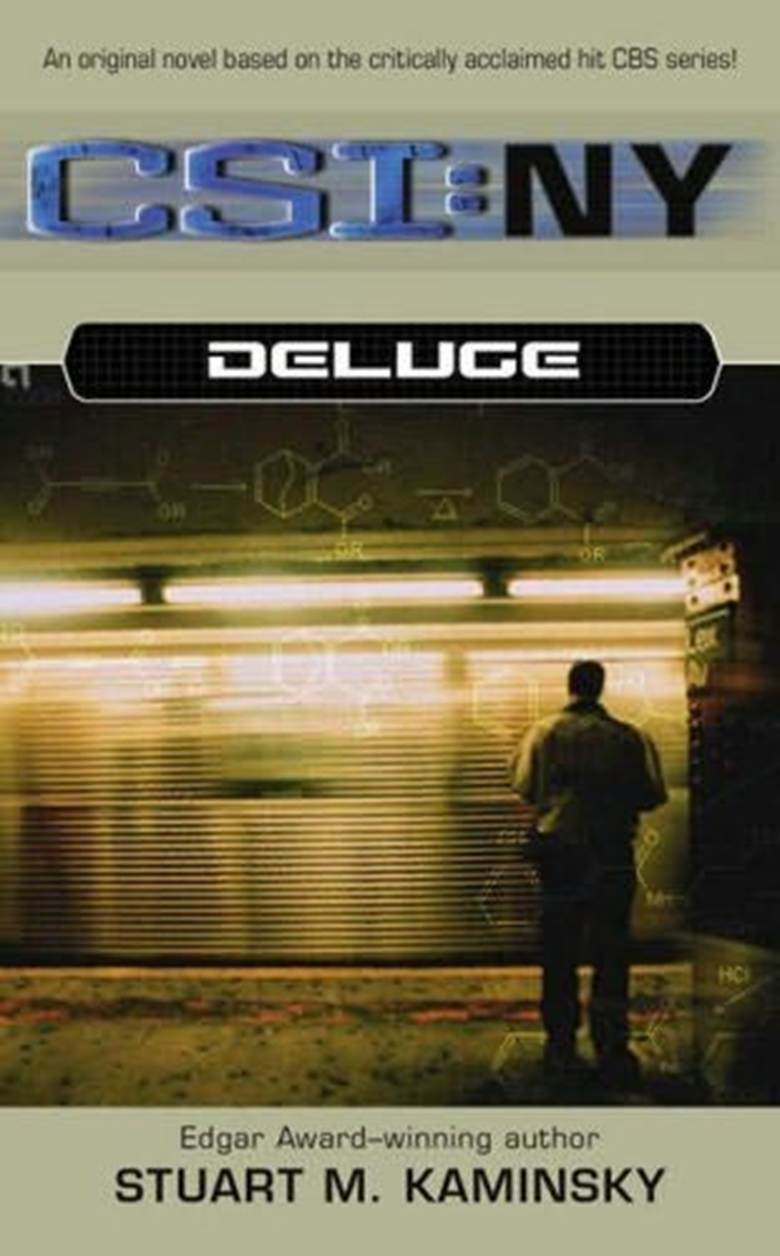

Stuart Melvin Kaminsky

Deluge

The third book in the CSI: New York series, 2007

Thanks to Lee Lofland for his continuing help and his expertise.

SEVEN INCHES OF RAIN had fallen in Central Park. Worms inched out of warm mud in a doomed search for dry ground. Homeless men and women had long since gathered whatever possessions they had in makeshift bundles and made their way out of the park in soggy shoes and sneakers.

One of the homeless, a woman named Florence who was prone to delusions, wandered off the no-longer-discernable path and into the lake where she drowned, clutching a photograph of two dogs.

Signs were posted for people to stay out of the park, though the park seemed no more a victim of the deluge than the rest of the island of Manhattan.

But it would be all right, everything would be under control, if the weather got no worse. But it did get worse. Much worse.

* * *

The hard-driving September rain slapped against Dexter Hughes's rain poncho as he stepped over the river that rushed wildly next to the curb on the north side of Eighty-seventh Street. Thunder crashed in the 9 a.m. morning dimness. It was music; loud, drums, brass. Music.

He paused to catch his breath and to make sure his St. Paul medal was still around his neck and that none of his wares had escaped from the bulging plastic Bloomingdale's bags he held.

Nothing was lost. Dexter smiled. Yes, it was his kind of day. The radio had said it would probably be the heaviest rain the city had experienced in more than a century. Eight inches, maybe more, today alone.

The malodorous water rushed along the street next to the curb in front of him. An empty plastic pill bottle bobbed down the river. Dexter could make out a blue disposable razor, a filthy work glove, a discarded Metrocard, a mangled white ballpoint pen and the inch-high upper torso of a Betty Boop figurine.

Half a block away he could make out men and women running, leaping, hunching over with purses, newspapers and umbrellas over their heads. It was going to be a good day.

He pushed open the door of the Brilliance Deli and stepped inside. The narrow aisle leading to the six tables in the rear was thick with people exuding heavy, musty dampness, jammed together waiting for a break in the rain, a break that wasn't coming. They drank coffee, ate muffins and bagels and donuts, made calls on their cell phones, lost their tempers. Waited.

Dexter looked at Achmed, the deli's owner, who paused in his rush from grill to cash register. Dexter caught his eye and Achmed nodded his approval.

Dexter called out, "Umbrellas five dollars, rain ponchos three dollars."

He had picked up three dozen umbrellas and the same number of ponchos from Alvino Lopez at a graffitti-covered garage on 101st Street. He would have charged a dollar more if the merchandise did not carry the distinctive smell of motor oil.

Arms stretched out, eager for his wares. Dexter served out rain gear to cash-filled hands.

Rain beat down on the awning in front of the Brilliance. So did runoff water from the roof of the three-story brick building. A hole in the awning looked like an open faucet.

The sight was a godsend for Dexter, a sign to those huddled inside the deli that they needed protection.

Under his poncho, Dexter was a stick figure, as black and narrow as one of his umbrellas. Once, not all that many years ago, Dexter Hughes had commanded combat companies in battle in two wars. In the second of those wars, a small steel ball, one of hundreds released from a single bomb, had screeched through the night and torn out his right eye, taking part of the socket with it. Friendly fire tragedy. The army had fitted him with a state-of-the-art eye that looked natural enough if his good eye happened to be facing the same direction as the artificial one.

"Umbrellas imported from the South American rain forests, five dollars," Dexter called over the rain and voices. "Ponchos from Central America that defy rain, three dollars."

He shrugged inside his poncho to demonstrate how the water flew off. Customers nearby took a step back and then moved forward again. Ten-and twenty-dollar bills were held out.

"Umbrella." "Poncho." "Umbrella and a poncho, ten dollars. I need change, single dollar bills."

Hands were still reaching. Dexter shoved bills in his pockets. The Bloomingdale's bags grew lighter.

"That's it," said Dexter, giving out change for a twenty to a man who reeked of wet tobacco.

His bags empty, Dexter was considering a run back to the garage on 101st for more goods. Few wanted the rain to continue, but Dexter was one of the few.

"What the hell?" came a man's voice.

"Oh my God," said a woman.

"What is it?" said another woman. "What?"

They were looking over Dexter's shoulder. He turned and saw red rain gush through the tear in the awning.

Dexter could smell it. He had smelled it in two wars. Blood. He knew the look of blood in water, the dark, languid look.

The people in the deli and outside of it under the awning were talking. He sensed that Achmed had made his way through the crowd.

Dexter stepped out into the rain, avoiding the bloody stream. He looked up, blinking through the downpour.

Three stories above him, Dexter could see a man standing at the edge of the roof, something in his hand. The man was wearing a dark GI raincoat. The man's eyes met Dexter's. A torrent of blood and water poured from a drainage spout on the roof just beneath the man, who slowly straightened and turned. Then the man was gone.

Dexter wouldn't be going back to pick up more umbrellas and ponchos and he wouldn't be waiting around for the police. He had had more than enough encounters with the police, thank you.

Dexter turned and headed into the deluge, resisting the urge to look over his shoulder and up at the roof behind him.

Dexter knew the man on the roof and the man on the roof knew him.

* * *

The man limped away from the edge of the roof. The black man in the yellow poncho had met his gaze. They had recognized each other. Then the black man had moved away into the almost painful slam of thick, demanding rain.

A half century of stones on the roof mixed with the detritus of broken beer bottles, shriveled condoms, and discarded syringes that were carried away in the red river. The potted plants lined up against the knee-high walls were overflowing and adding black dirt and chemicals to the rushing water.

The flat rooftop had a simple drainage system that allowed rainwater to run off to prevent ponding, which would damage the roof covering. Around the outside edge of the rooftop were low places that served as funnels. The funnels or scuppers emptied into holes in the parapet wall toward both the street and alley. Inside these scuppers were rusting screens to catch debris. From time to time, particularly after a hard rain, someone would clear away the debris from the screen. The woman that the man had just killed had been on the roof to clear those screens.

The man was transfixed, nearly hypnotized, knowing he should move, get away. He had a lot left to do and very little time. Instead he stared down at the dead woman.

She was spread-eagled, dress hiked up, skin ex-posed. There was a look of horror on her face, horror and pain. Her hair was beaten back, clamped to her head. She looked almost bald. Her open mouth was filled with water that bubbled as if from an overfilled pool.

The man hadn't known what he would feel when he killed her. He'd hoped that he wouldn't regret it, wouldn't be haunted, wouldn't shake or weep. He wanted to savor the moment. He wanted elation, satisfaction, not this dull, dreamy sensation echoing to the beat of thoughtless, demanding rain.

Next page