First Mariner Books edition 2004

Copyright 2003 by Paul Theroux

Postscript copyright 2004 by Paul Theroux

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

ISBN -13 978-0-618-13424-3 ISBN -10 0-618-13424-7

ISBN -13 978-0-618-44687-2 (pbk.) ISBN -10 0-618-44687-7 (pbk.)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edtion as follows:

Theroux, Paul, date.

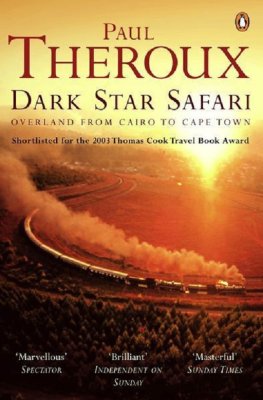

Dark star safari : overland from Cairo to

Cape Town / Paul Theroux.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-618-13424-7

ISBN 0-618-44687-7 (pbk.)

1. AfricaDescription and travel. I. Title.

DT 12.25 . T 48 2003

916.04'329dc21 2002032710

e ISBN 978-0-547-52677-5

v2.0313

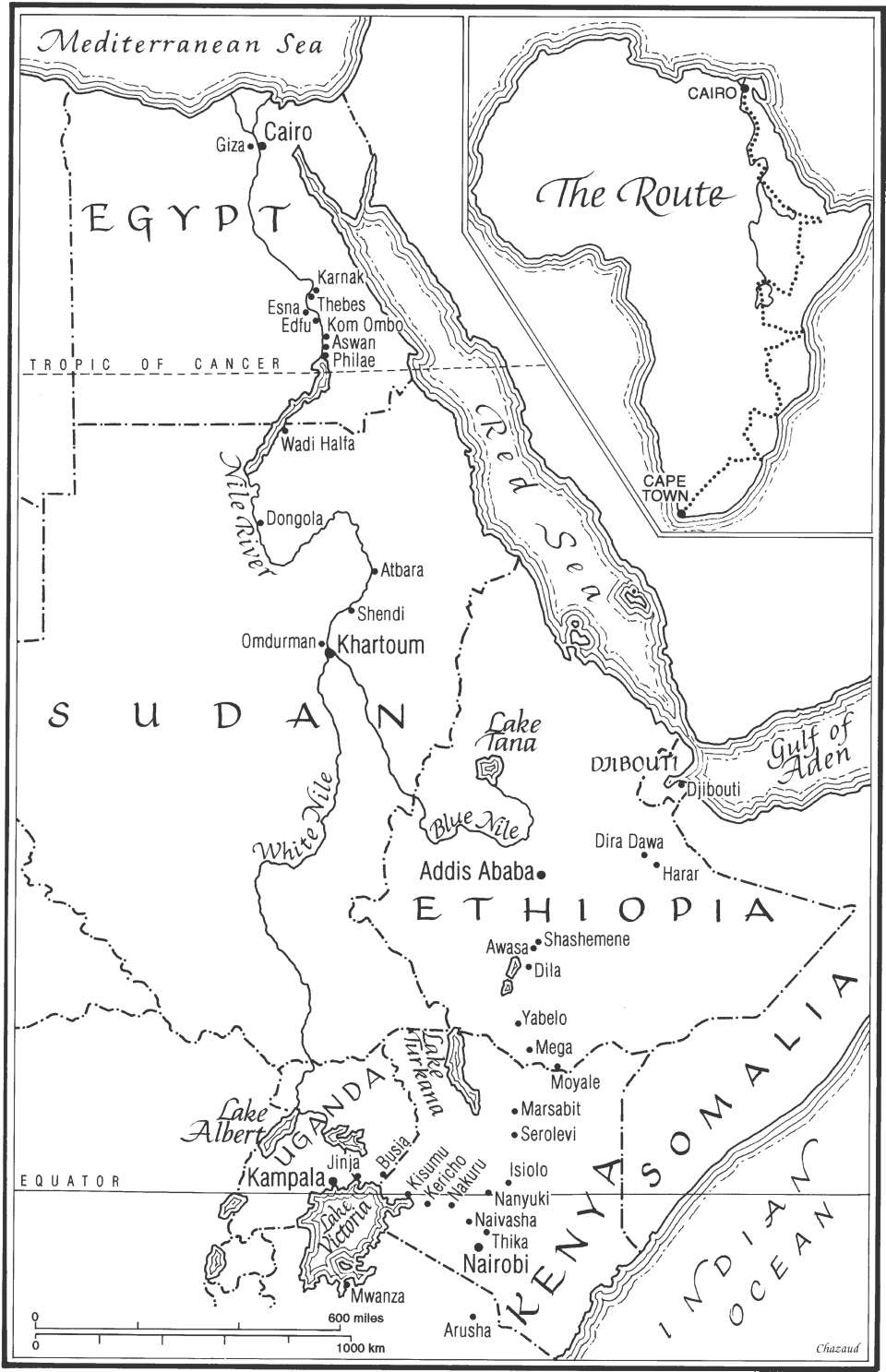

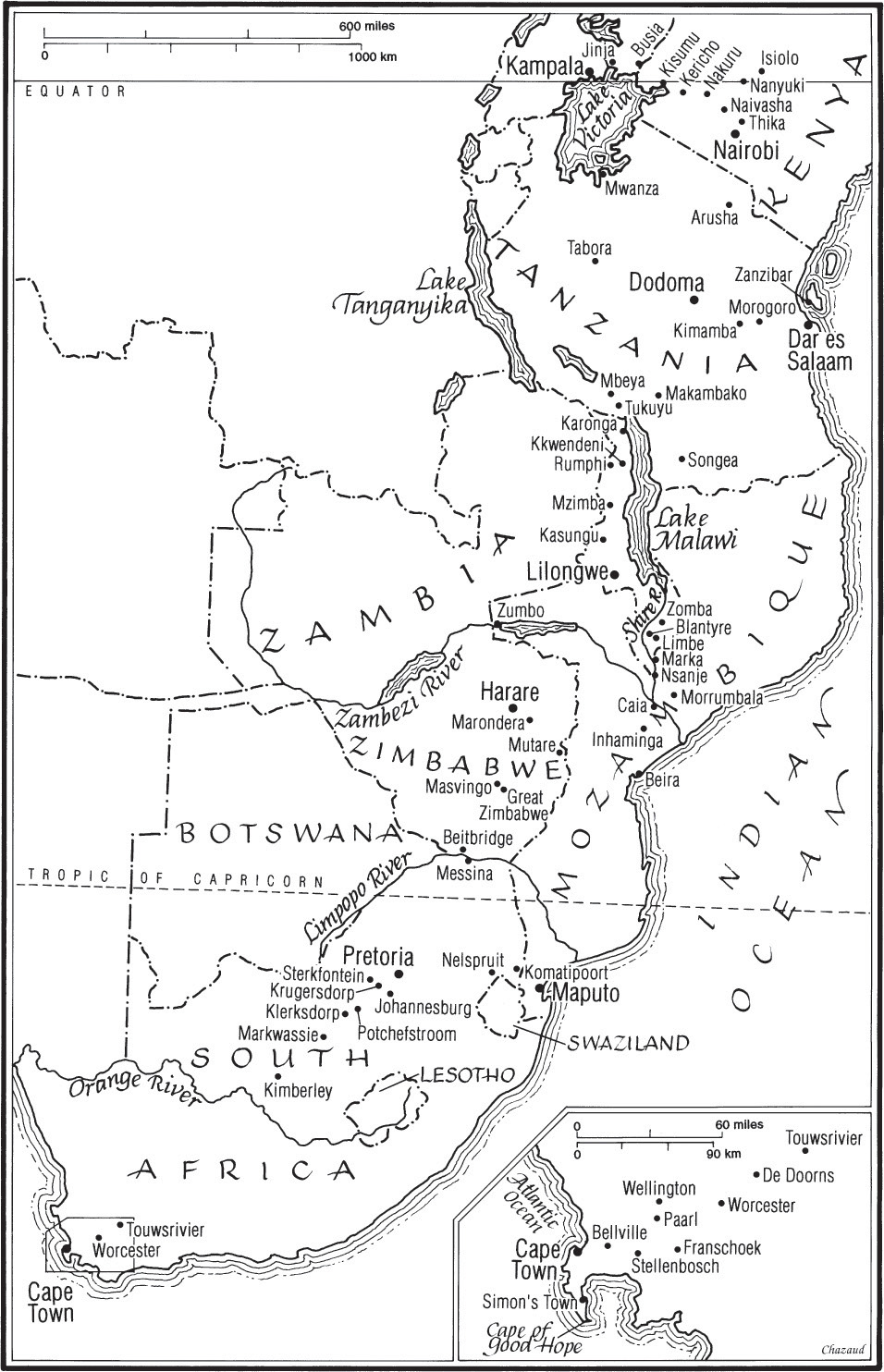

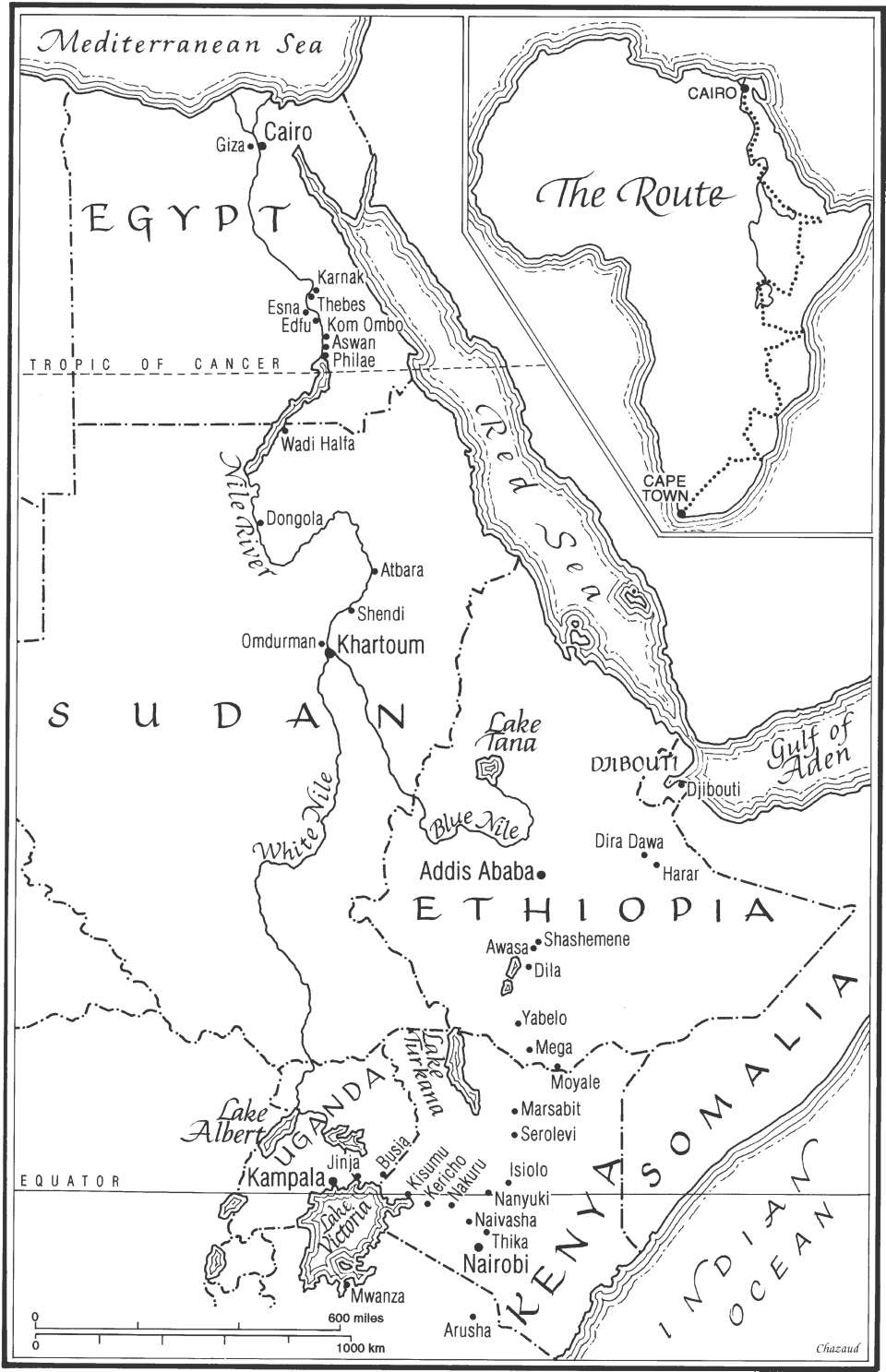

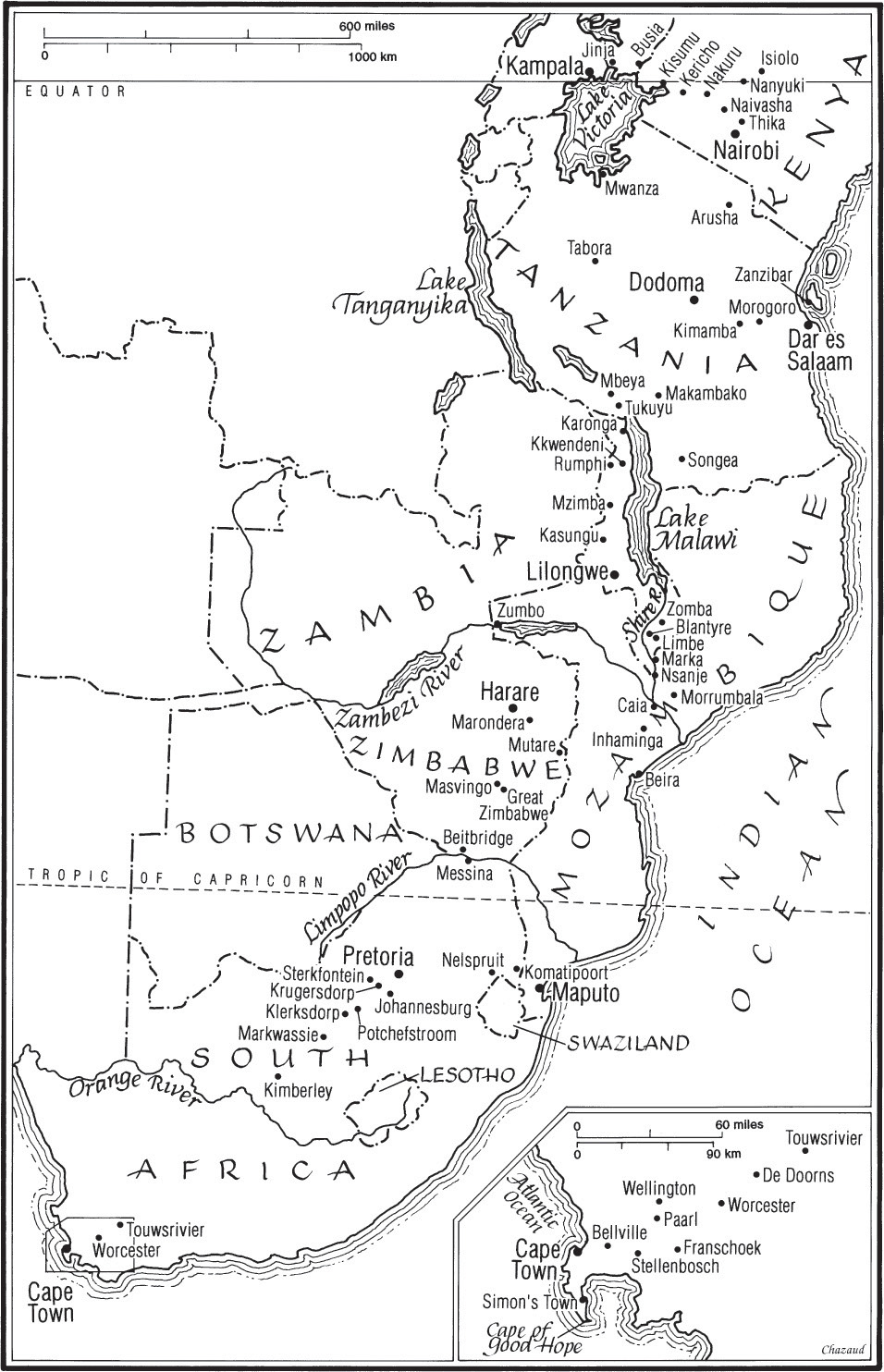

Maps by Jacques Chazaud

Excerpt from Faith Healing from Collected Poems by Philip Larkin.

Copyright 1988,1989 by the Estate of Philip Larkin.

Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

For my mother, Anne Dittami Theroux,

on her ninety-second birthday

Lighting Out

A LL NEWS out of Africa is bad. It made me want to go there, though not for the horror, the hot spots, the massacre-and-earthquake stories you read in the newspaper; I wanted the pleasure of being in Africa again. Feeling that the place was so large it contained many untold tales and some hope and comedy and sweetness, toofeeling that there was more to Africa than misery and terrorI aimed to reinsert myself in the bundu, as we used to call the bush, and to wander the antique hinterland. There I had lived and worked, happily, almost forty years ago, in the heart of the greenest continent.

To skip ahead, I am writing this a year later, just back from Africa, having taken my long safari and been reminded that all travel is a lesson in self-preservation. I was mistaken in so muchdelayed, shot at, howled at, and robbed. No massacres or earthquakes, but terrific heat and the roads were terrible, the trains were derelict, forget the telephones. Exasperated white farmers said, It all went tits-up! Africa is materially more decrepit than it was when I first knew ithungrier, poorer, less educated, more pessimistic, more corrupt, and you cant tell the politicians from the witch doctors. Africans, less esteemed than ever, seemed to me the most lied-to people on earthmanipulated by their governments, burned by foreign experts, befooled by charities, and cheated at every turn. To be an African leader was to be a thief, but evangelists stole peoples innocence, and self-serving aid agencies gave them false hope, which seemed worse. In reply, Africans dragged their feet or tried to emigrate, they begged, they pleaded, they demanded money and gifts with a rude, weird sense of entitlement. Not that Africa is one place. It is an assortment of motley republics and seedy chiefdoms. I got sick, I got stranded, but I was never bored. In fact, my trip was a delight and a revelation. Such a paragraph needs some explanationat least a book. This book perhaps.

As I was saying, in those old undramatic days of my schoolteaching in the bundu, folks lived their lives on bush paths at the ends of unpaved roads of red clay, in villages of grass-roofed huts. They had a new national flag to replace the Union Jack, they had just gotten the vote, some had bikes, many talked about buying their first pair of shoes. They were hopeful and so was I, a teacher living near a settlement of mud huts among dusty trees and parched fields. The children shrieked at play; the women, bent doublemost with infants slung on their backshoed patches of corn and beans; and the men sat in the shade stupefying themselves on chibuku, the local beer, or kachasu, the local gin. That was taken for the natural order in Africa: frolicking children, laboring women, idle men.

Now and then there was trouble: someone transfixed by a spear, drunken brawls, political violence, goon squads wearing the ruling-party T-shirt and raising hell. But in general the Africa I knew was sunlit and lovely, a soft green emptiness of low, flat-topped trees and dense bush, bird squawks, giggling kids, red roads, cracked and crusty brown cliffs that looked newly baked, blue remembered hills, striped and spotted animals and ones with yellow fur and fangs, and every hue of human being, from pink-faced planters in knee socks and shorts to brown Indians to Africans with black gleaming faces, and some people so dark they were purple. The predominant sound of the African bush was not the trumpeting of elephants nor the roar of lions but the coo-cooing of the turtledove.

After I left Africa, there was an eruption of news about things going wrong, acts of God, acts of tyrants, tribal warfare and plagues, floods and starvation, bad-tempered political commissars, and little teenage soldiers who were hacking people. Long sleeves? they teased, cutting off hands; short sleeves meant lopping the whole arm. One million people died, mostly Tutsis, in the Rwanda massacres of 1994. The red African roads remained, but they were now crowded with ragged, bundle-burdened, fleeing refugees.

Journalists pursued them. Goaded by their editors to feed a public hungering for proof of savagery on earth, reporters stood near starving Africans in their last shaking fuddle and intoned on the TV news for people gobbling snacks on their sofas and watching in horror. And these peopletight close-up of a death rattlethese are the lucky ones.

You always think, Who says so? Had something fundamental changed since I was there? I wanted to find out. My plan was to go from Cairo to Cape Town, top to bottom, and to see everything in between.

Now African news was as awful as the rumors. The place was said to be desperate, unspeakable, violent, plague-ridden, starving, hopeless, dying on its feet. And these are the lucky ones. I thought, since I had plenty of time and nothing pressing, that I might connect the dots, crossing borders and seeing the hinterland rather than flitting from capital to capital, being greeted by unctuous tour guides. I had no desire to see game parks, though I supposed at some point I would. The word safari, in Swahili, means journey; it has nothing to do with animals. Someone on safari is just away and unobtainable and out of touch.

Out of touch in Africa was where I wanted to be. The wish to disappear sends many travelers away. If you are thoroughly sick of being kept waiting at home or at work, travel is perfect: let other people wait for a change. Travel is a sort of revenge for having been put on hold, having to leave messages on answering machines, not knowing your partys extension, being kept waiting all your working lifethe homebound writers irritants. Being kept waiting is the human condition.

I thought, Let other people explain where I am. I imagined the dialogue:

When will Paul be back?

We dont know.

Where is he?

Were not sure.

Can we get in touch with him?

No.

Travel in the African bush can also be a sort of revenge on cellular phones and fax machines, on telephones and the daily paper, on the creepier aspects of globalization that allow anyone who chooses to get his insinuating hands on you. I desired to be unobtainable. Kurtz, sick as he is, attempts to escape from Marlows riverboat, crawling on all fours like an animal, trying to flee into the jungle. I understood that.

Next page