By Train Through China

"Theroux's genius is in his clear-eyed rendition of a fresh world and the deeper observations he attaches toit." Chicago Tribune

A MARINER BOOK

H OUGHTON M IFFLIN C OMPANY Boston New York

First Mariner Books edition 2006

Copyright 1988 by Paul Theroux

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Visit our Web site: www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Dataes

Theroux, Paul.

Riding the iron rooster : by train through China / Paul Theroux.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York : Putnam's, c1988.

ISBN -13: 978-0-618-65897-8 (pbk.)

ISBN -10; 0-618-65897-1 (pbk.)

1. Theroux, PaulTravelChina. 2. ChinaDescription

and travel. 3. Railroad travelChina. I. Title.

DS 712. T 446 2006

915.1'0458dc22 2006028745

Printed in the United States of America

MV 10 9 8 7 6 5 4

To Anne

CONTENTS

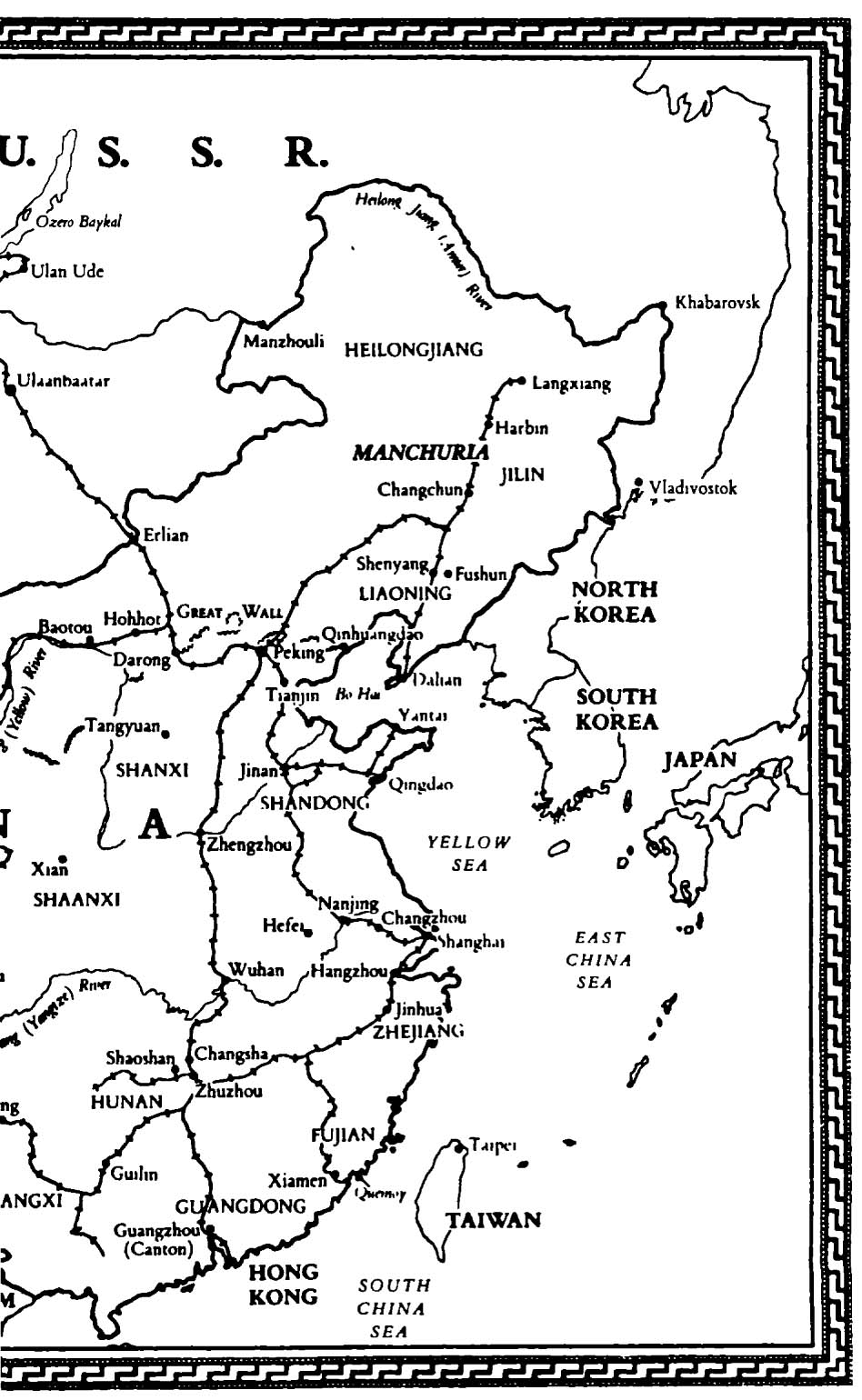

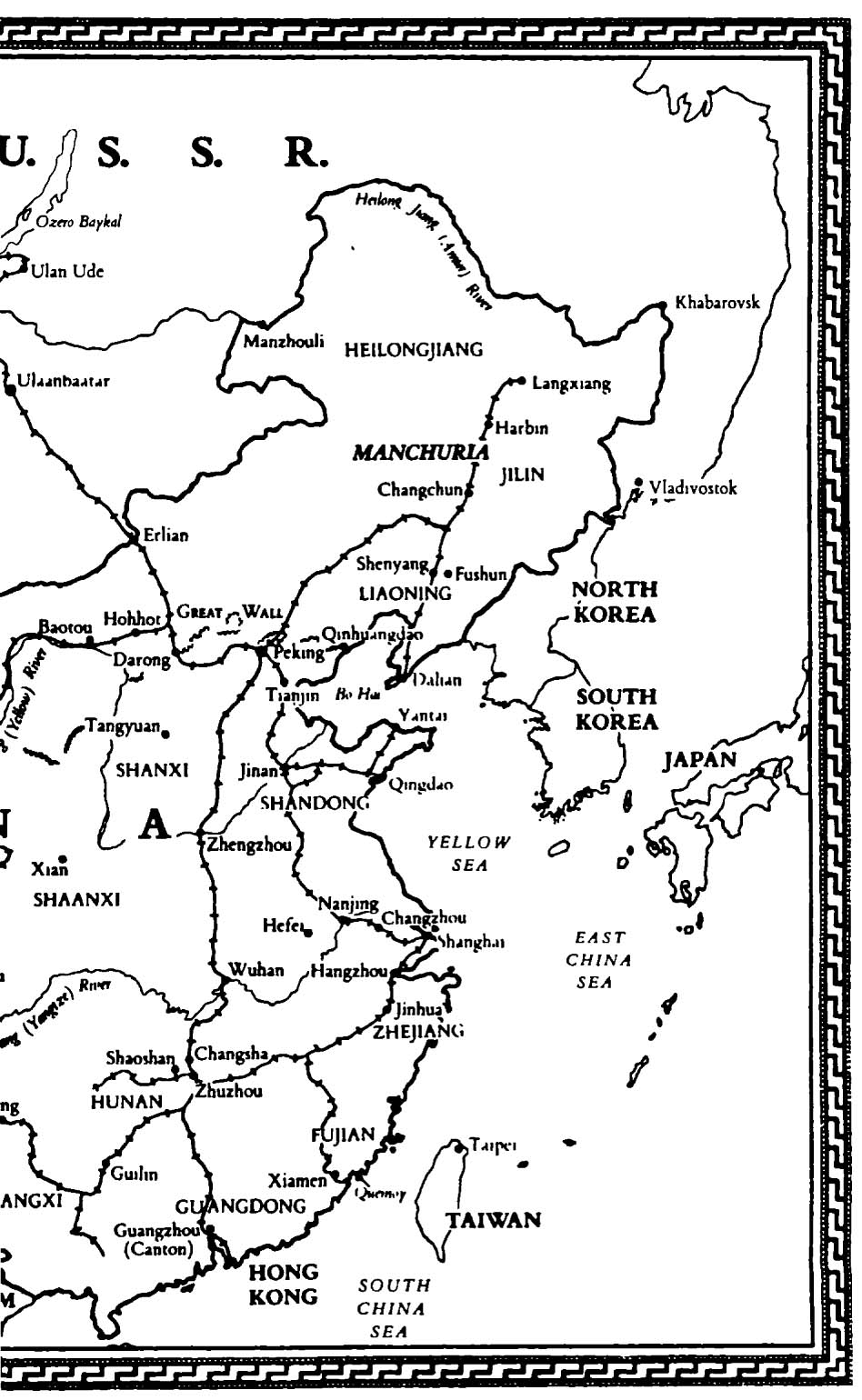

1. The Train to Mongolia 15

2. The Inner Mongolian Express to Datong: Train Number 24 65

3. Night Train Number 90 to Peking 77

4. The Shanghai Express 104

5. The Fast Train to Canton 145

6. Train Number 324 to Hohhot and Lanzhou 166

7. The Iron Rooster 185

8. Train Number 104 to Xian 214

9. The Express to Chengdu 229

10. The Halt at Emei Shan: Train Number 209 to Kunming 244

11. The Fast Train to Guilin: Number 80 261

12. The Slow Train to Changsha and Shaoshan "Where the Sun Rises" 277

13. The Peking Express: Train Number 16 290

14. The International Express to Harbin: Train Number 17 311

15. The Slow Train to Langxiang: Number 295 324

16. The Boat Train to Dalian: Number 92 343

17. On the Lake of Heaven to Yantai 361

18. The Slow Train to Qingdao: Number 508 373

19. The Shandong Express to Shanghai: Train Number 234 385

20. The Night Train to Xiamen: Number 375 396

21. The Qinghai Local to Xining: Train Number 275 415

22. The Train to Tibet 435

A peasant must stand a long time

on a hillside with his mouth open

before a roast duck flies in.

CHINESE PROVERB

The movements which work revolutions

in the world are born out of the dreams and

visions in a peasants heart on a hillside.

JAMES JOYCE, Ulysses

1. The Train to Mongolia

The bigness of China makes you wonder. It is more like a whole world than a mere country. "All beneath the sky" (Tianxia) was one Chinese expression for their empire, and another was "All between the four seas" (Sihai). These days people go there to shop, or because they have a free week and the price of a plane ticket. I decided to go because I had a free year. And the Chinese proverb We can always fool a foreigner I took to be a personal challenge. To get to China without leaving the ground was my first objective. And then I wanted to stay for a whilein China, on the ground, going all over the place.

The railway was the answer. It was the best way of traveling to Peking (Beijing) from London, where I happened to be. Every modern account of Chinese travel I had read seemed weakened by jet lagan unhappy combination of fatigue and insomnia. "We were very tired there," is a common remark by travelers to China, the gasping sightseers and bargain hunters. This desire to sit down could be maddening in a country where everyone else was full of beans. Wasn't that the whole point of the Chinesethat they were always on the go? Even after five thousand years of continuous civilization they were still at it. And one of the lessons of Chinese history is that they never know when to stop.

I had seen China in the winter of 1980. It looked bleak and exhausted, all baggy blue suits and unconvincing slogans on red banners. If you said, "Surely these people ought to be wearing something more than cloth slippers in this snow and ice," you were told how lucky they were and that they used to go barefoot. The whole country was dark brown from the soot and dust. There were few trees. I went bird-watching but saw only crows and sparrows and the sort of grubby pigeons that look like flying rats. The rarer birds the Chinese stuff into their mouths.

The Chinese, then, would point through the drizzle to where a factory was coughing up smoke at the end of a muddy lane; where bent-over people were dragging wooden carts loaded with pig iron. And they would say, 'This was once all prostitutes and bad elements and gambling and bright lights and dance halls." You were supposed to be glad this sinful frivolity was gone, and fascinated by the factories, but I just sighed. I saw young women destroying themselves in mills, smashing their pretty fingers on wooden looms, or blinding themselves doing finicky "forbidden-stitch" embroidery. An official Chinese statistic said that there were seventy million portraits of Chairman Mao on Chinese walls. People whispered when they mentioned his name. Stricken and overworked, they said, "Owing to the success of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution..." And they served me bowel-shattering meals.

Americans came back from China saying, Acupuncture! No flies! No tipping! They give you your used razor blades back! They work like dogs! They eat cats! They're so frisky! And Americans even praised Chairman Mao, unaware that many Chinese were privately sick of him.

But that was the past, my brother Gene said, and he told me that I would be a fool not to go now. China had become a different place, and it was changing from day to day. He knew what he was talking about: he had traveled to China 109 times since 1972, as a lawyerone of the new taipans. I planned to go in the spring this time. I kept telling myself: New people, new scenesfresh air and the pleasure of anonymity. There were two ways of doing itthe way of the English poet Philip Larkin, who said, "I wouldn't mind seeing China if I could come back the same day." And there was total immersion.

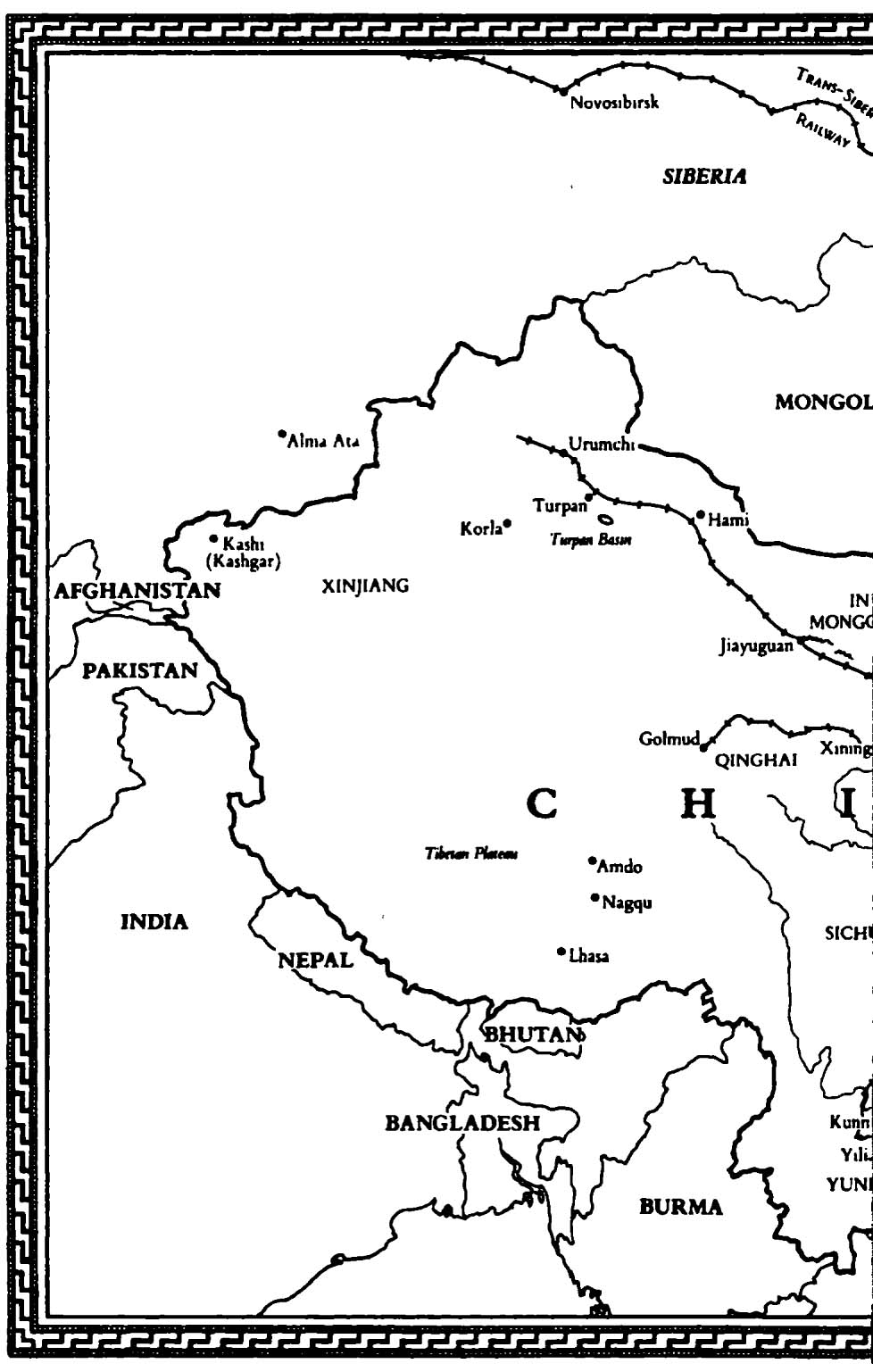

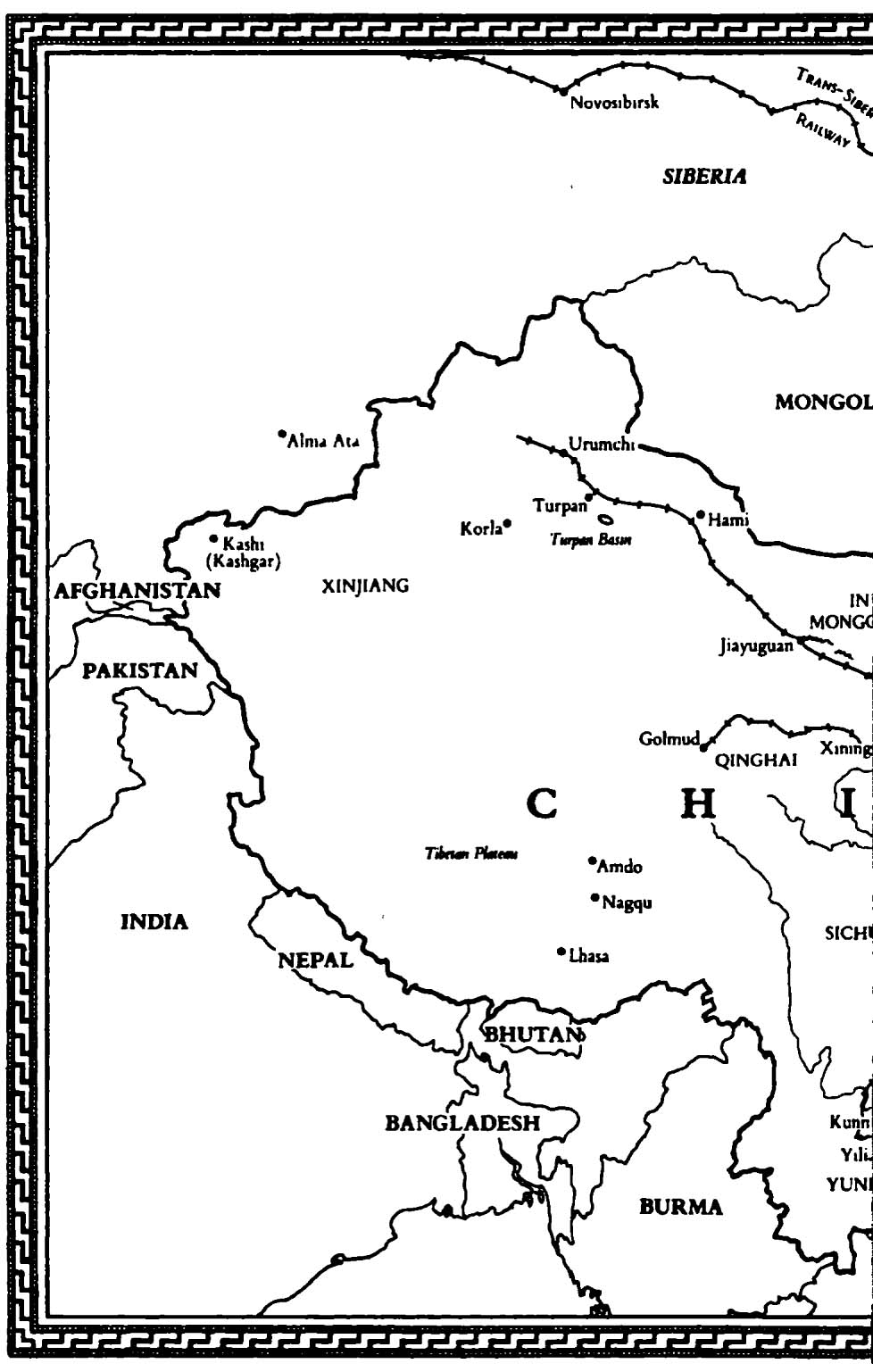

My idea was to take a train in London, go to Paris, keep going, head for Germany and Poland, maybe stop in Moscow, take the Trans-Siberian, get off in Irkutsk, take the Trans-Mongolian, and spend May Day in Ulan Bator. Essentially the way to China was the train to Mongolia. It was traveling slowly across Asia's wide forehead and then down into one of its eyes, Peking.

Going to Mongolia that way ought to be relaxing, I thought. And it ought to give me a feeling of accomplishment. I would read a little and make notes and eat regular meals and look out of the window. I pictured myself in a sleeping compartment, reading Elmer Gantry and hearing the hoot of the train whistle echoing on the steppes, and thinking: Pretty soon I'll be thereas I drew the blanket up to my chin. And then one day I would snap up the blind and see a yak standing in an immensity of brown sand and I would know it was the Gobi Desert. A day or so later, the landscape would be green and people would be standing knee-deep in rice fields, wearing lamp-shade hatsall of thatand I would step off the train into China.

It was not that simple. It never is, and so an explanation is necessarythis book. It was my good fortune to be wrong: being mistaken is the essence of the traveler's tale. What I had thought of as the simplest way of getting thereeight trains from London to the Chinese borderturned out to be odd and unexpected. Sometimes it seemed like real travel, full of those peculiar discoveries and satisfactions. But more often it was as if I had lost my footing in London and had fallen down a long flight of stairs, perhaps one of those endless staircases designed by a surrealist painter, and down I went, bump-bump-bump, and across the landing, and down again, bump-bump-bump, until I had fallen halfway around the world.

Next page