Text 2007 by Colin Wilson

Layout and Design 2007 by Merlin Publishing

First US Edition 2014 by Skyhorse Publishing

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications.

For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018

or

.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-1-62914-193-0

eISBN 978-1-62914-293-7

Printed in the United States of America

To Robert K. Ressler

A Plague of Murder

In 1977, FBI Special Agent Robert Ressler first used the term serial killer after a visit to Bramshill Police Academy, near London, where someone referred to a serial burglar. The inspired coinage was soon in general use to describe killers such as necrophile Ed Kemper (10 victims), schizophrenic Herb Mullin (14), and homosexual mass murderers Dean Corll (27) and John Wayne Gacy (32). Then in 1980, in Colombia, Pedro Lopez, the Monster of the Andes, confessed to murdering 310 prepubescent girls; three years later, a derelict named Henry Lee Lucas claimed to have killed 350 victims. Clearly, these sprees were on a scale beyond anything known in the history of crimeeven the French Bluebeard, Gilles de Rais, executed in 1440, was believed to have killed no more than 50 children. In more recent years, the American Pee Wee Gaskins killed an estimated 110, Red Ripper Andrei Chikatilo 56, his fellow Russian Anatoly Onoprienko 52, and the British doctor Harold Shipman between 215 and 260. There was an obvious need for Resslers new term to describe this horrific phenomenon.

Understanding it is rather more difficult. But I can claim at least one qualification. In the late 1950s, I had decided it was about time someone compiled an encyclopedia covering all the most notorious murder cases. The subject of crime had always interested me, and I was engaged in writing my first novel, Ritual in the Dark, about a mass murderer based on Jack the Ripper. I had collected a considerable library of secondhand books on true crime with titles like Scales of Justice or Murderers Sane and Mad. But if I wanted to look up a specific fact about a murderer, such as the date he was hanged, I had to recollect which volume in my crime library contained a chapter about him. I decided to remedy this deficiency by writing an alphabetical encyclopedia of murder, which was published in 1961. Since then many writers have followed suit with encyclopedias of female killers, sex killers, serial killers, even one devoted entirely to Jack the Ripper.

It was while compiling the Encyclopedia of Murder that I first noticed a variety of murder that I was unable to fit into the old classifications: apparently motiveless murders. In 1952, for example, a nineteen-year-old clerk named Herbert Mills sat next to a forty-eight-year-old housewife in a Nottingham cinema and decided that she would make a suitable victim for an attempt at the perfect murder; he met her by arrangement the next day, took her for a walk, and strangled her under a tree. It was only because he felt the compulsion to boast about his perfect crime that he was caught and hanged.

In July 1958, Norman Foose stopped his jeep in the town of Cuba, New Mexico, raised his hunting rifle, and shot dead two Mexican children; pursued and arrested, he said he was trying to do something about the population explosion.

In February 1959, a pretty blonde named Penny Bjorkland accepted a lift from a married man in California and, without provocation, killed him with a dozen shots. After her arrest she explained that she wanted to see if she could kill and not worry about it afterwards. Psychiatrists found her sane.

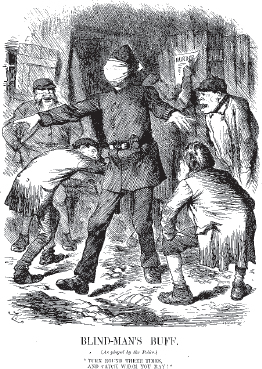

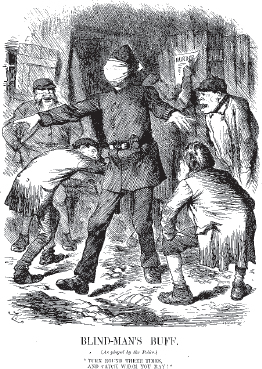

An 1888 Punch cartoon satirizes the polices inability to find the Whitechapel murderer. The nineteenth century saw the advent of the sex crime.

In April 1959, a man named Norman Smith took a pistol and shot a woman (who was watching television) through an open window. He did not know Hazel Woodard; the impulse had simply come over him as he watched a TV show called The Sniper.

The Encyclopedia of Murder appeared in 1961, with a section on motiveless murder; by 1970 it was clear that this was, in fact, a steadily developing trend. In many cases, oddly enough, it seemed to be linked to a slightly higher-than-average IQ in the murderers. Herbert Mills wrote poetry and read some of it above the body of his victim. The Moors Murderer Ian Brady justified himself by quoting de Sade, and in a later correspondence with him I had ample opportunity to observe that he was highly intelligent. Melvin Rees, a mild, quiet-spoken jazz pianist, committed a series of sex murders, including the slaying of an entire family, and told a friend: You cant say its wrong to killonly individual standards make it right or wrong. Charles Manson evolved an elaborate racist ideology to justify the crimes of his Family. San Franciscos Zodiac killer wrote his letters in cipher and signed them with signs of the zodiac. John Frazier, a dropout who slaughtered the family of an eye surgeon, Victor Ohta, left a letter signed with suits from the tarot pack. In November 1966, Robert Smith, an eighteen-year-old student, walked into a beauty parlor in Mesa, Arizona, ordered five women and two children to lie on the floor, and then shot them all in the back of the head. Smith was in no way a problem youngster; his relations with his parents were good and he was described as an excellent student. He told the police: I wanted to get known, to get myself a name.