THE MAMMOTH

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF

UNSOLVED

MYSTERIES

Also available

The Mammoth Book of Arthurian Legends

The Mammoth Book of Battles

The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror 2000

The Mammoth Book of Best New Science Fiction 13

The Mammoth Book of Bridge

The Mammoth Book of British Kings & Queens

The Mammoth Book of Cats

The Mammoth Book of Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Seriously Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Egyptian Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of Endurance and Adventure

The Mammoth Book of Future Cops

The Mammoth Book of Fighter Pilots

The Mammoth Book of Haunted House Stories

The Mammoth Book of Heroes

The Mammoth Book of Heroic and Outrageous Women

The Mammoth Book of Historical Whodunnits

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened Battles

The Mammoth Book of How it Happened in Britain

The Mammoth Book of How It Happened World War II

The Mammoth Book of Jack the Ripper

The Mammoth Book of Jokes

The Mammoth Book of Legal Thrillers

The Mammoth Book of Life Before the Mast

The Mammoth Book of Literary Anecdotes

The Mammoth Book of Locked-Room Mysteries and Impossible Crimes

The Mammoth Book of Men OWar

The Mammoth Book of Murder

The Mammoth Book of Murder and Science

The Mammoth Book of On The Road

The Mammoth Book of Oddballs and Eccentrics

The Mammoth Book of Private Lives

The Mammoth Book of Seriously Comic Fantasy

The Mammoth Book of Sex, Drugs & Rock n Roll

The Mammoth Book of Soldiers at War

The Mammoth Book of Sports & Games

The Mammoth Book of Sword & Honour

The Mammoth Book of True Crime (New Edition)

The Mammoth Book of True War Stories

The Mammoth Book of Unsolved Crimes

The Mammoth Book of War Correspondents

The Mammoth Book of UFOs

The Mammoth Book of the Worlds Greatest Chess Games

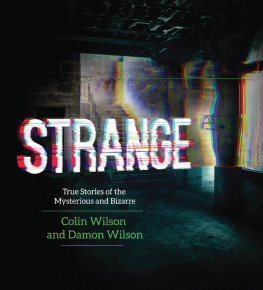

Constable & Robinson Ltd

3 The Lanchesters

162 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 9ER

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd 2000

Copyright Colin Wilson and Damon Wilson, 2000

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication data is available from the British Library

ISBN 1-84119-172-8

ISBN 978-1-84119-172-0

eISBN 978-1-78033-705-0

Printed and bound in the EU

10 9 8 7 6 5

Authors Note

This book contains most of the chapters from two earlier works: An Encyclopedia of Unsolved Mysteries and Unsolved Mysteries Past and Present. This explains why some chapters contain nuggets of information that can be found in other chapters: they were originally part of different books. We have not removed such repetitions, because they are always relevant to the chapter in which they occur, and readers who read this book piecemeal will probably not notice them anyway.

CW and DW

Introduction

In 1957 the science writer Jacques Bergier made a broadcast on French television that caused a sensation. He was discussing one of the great unsolved mysteries of prehistory, the sudden disappearance of the dinosaurs about sixty-five million years ago. He suggested that the dinosaurs had been wiped out by the explosion of a star fairly close to our solar system a supernova. He then went on to make the even more startling suggestion that the explosion may have been deliberately caused by superbeings who wanted to wipe out the dinosaurs and to give intelligent mammals a chance.

Even the first part of his theory was dismissed by scientists as the fantasy of a crank, and the reaction was no better when in 1970 Bergier repeated it in a book called Extra-Terrestrials in History, which began with a chapter called The Star that Killed the Dinosaurs. But five years later an American geologist named Walter Alvarez was studying a thin layer of clay on a hill side in Italy the clay that divides the age of the dinosaurs (Mesozoic) from our own age of mammals and brooding on this question of what had wiped out whole classes of animal. He took a chunk from the hillside back to California, and showed it to his father, the physicist Luis Alvarez, with the comment: Dad, that half-inch layer of clay represents the period when the dinosaurs went out, and about 75 per cent of the other creatures on the earth.

His father was so intrigued that he subjected the clay to labouratory tests, and found it contained a high proportion of a rare element called iridium, a heavy element that usually sinks to the middle of planets, but which is thrown out by explosions. Alvarez also gave serious consideration to the idea of an exploding star, and only dismissed it when further tests showed an absence of a certain radioactive platinum that would also be present in a supernova explosion. The only other alternative was that the earth had been struck by a giant meteorite, which had filled the atmosphere with steam and produced a greenhouse effect that had raised the temperature by several degrees.

Modern crocodiles and alligators can survive a temperature of about 100 degrees C; but two or three degrees higher is too much for them, and they die. This is almost certainly what happened to the dinosaurs, about sixty-five million years ago. And that is why this present book contains no entry headed: What became of the dinosaurs? We know the answer. And we also know that Bergiers lunatic fringe theory was remarkably close to the truth.

This is the basic justification for a volume like this. It underlines the point that it is always dangerous to draw a sharp, clear line between lunacy and orthodox science. In the article on spontaneous human combustion, I have quoted a modern medical textbook which states that spontaneous combustion is impossible, and that there is no point in discussing it. But the evidence is now overwhelming that spontaneous combustion not only occurs, but occurs fairly frequently.

In 1768 the French Academy of Sciences asked the great chemist Lavoisier to investigate a report of a huge stone that had hurtled from the sky and buried itself in the earth not far from where some peasants were working. Lavoisier was absolutely certain that great stones did not fall from the sky, and reported that the witnesses were either mistaken or lying; it was another half century before the existence of meteorites was accepted by science.

The poltergeist, or noisy ghost, is even more commonplace than spontaneous human combustion; at any given moment there are hundreds of cases going on all over the world. Yet in America scientists have formed a kind of defensive league called CSICOP (Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal) whose basic aim is to argue that the paranormal simply does not exist, and is an invention of cranks and pseudos. Anyone who has taken even the most superficial interest in the paranormal knows that such a view is not merely untenable, but that it represents a kind of wilful blindness.

Let us be quite clear about this. I am not arguing that scepticism is fundamentally harmful. Reason is the highest faculty possessed by human beings, and every moment of our lives demands a continuous assessment of probabilities. Our lives depend upon this assessment every time we cross a busy street. I have to judge the likelihood of that car or bus reaching me before I can step on to the opposite pavement. And when a scientist is confronted by the question of whether, let us say, an Israeli psychic can bend keys by merely stroking them, he can only appeal to his general experience of keys and try to assess the probabilities. Yet I think every scientist would agree that it would be wrong to make an

Next page