Praise for

THE SECOND TREE

Winner of the Pearson Writers Trust Non-Fiction Prize

The Second Tree is a disturbing book and a challenging read, both technically and emotionally, but it is one that should be on everyones list this fall. We can only hope an Elaine Dewar will always be on the sidelines, ready to guide us into the maze.

The Gazette (Montreal)

Dewar both entertains and clearly explains complex scientific concepts and the associated ethical and moral dilemmas. Anyone who labours under the false impression that science is a noble but dull enterprise largely untainted by human failings and vices should read The Second Tree.

Winnipeg Free Press

Dewar provides a comprehensive account of the last seven years of genomic science. She immerses herself in the biologists world of genetic experiments and describes the battles that were fought during the rush to sequence the human genome. The Second Tree is an excellent primer for anyone interested in understanding the history of genetics and biologys decade-long boom. Policy makers might even benefit from keeping Dewars book on their nightstands.

Literary Review of Canada

To Mom and Dad

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

the Lord God formed man from the dust of the earth. He blew into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being.

The Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east, and placed there the man whom He had formed. And from the ground, the Lord God caused to grow every tree that was pleasing to the sight and good for food, with the tree of life in the middle of the garden, and the tree of knowledge of good and bad

When the woman saw that the tree was good for eating and a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was desirable as a source of wisdom, she took of its fruit and ate. She also gave some to her husband, and he ate. Then the eyes of both of them were opened and they perceived that they were naked; and they sewed together fig leaves and made themselves loincloths

And the Lord God said, Now that the man has become like one of us, knowing good and bad, what if he should stretch out his hand and take also from the tree of life and eat, and live forever! So the Lord God banished him from the garden of Eden, to till the soil from which he was taken. He drove the man out, and stationed east of the garden of Eden the cherubim and the fiery ever-turning sword, to guard the way to the tree of life.

TANAKH, GENESIS 2 AND 3

INTRODUCTION

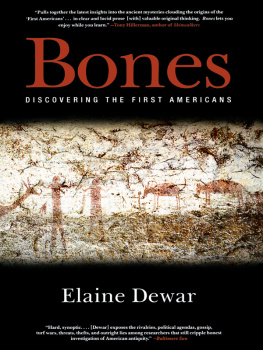

T his book, like a clone thrown up from a lilac bush, grew from another. I was working on a project about the origins of the first people to inhabit the Americas when I was introduced to a brand new set of ideasthe use of genetics to trace the movements of people over thousands of years. Anthropologists claimed that the DNA handed down to us from our mothers and grandmothers, all the way back to Eve, can tell us where we came from.

I had learned what little I knew of biology and genetics in high school in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, thirty-five years earlier. (I dont count a first-year university general science course that included four weeks of biology. I was so nervous at the lab test that I broke a specimen slide under a microscope. I failed it, but freed myself from my suicidal plan to go to medical school.) In high school, in my day, biology was all about divisions. We sliced the study of living things into botany and zoology. We committed to memory the classification scheme into which eighteenth-century biologists had pigeonholed life in its wondrous variety. We drew pictures of plant cells and their internal structures, and of single-celled animals and their organs. We tiptoed gingerly past Darwins evolution theory, to avoid raising the wrath of any fundamentalists lurking among us. There was no discussion of the molecules that living things are made of, even though the field known as molecular biology had made vast strides since 1953, when James D. Watson and Francis H. Crick made a model showing how deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), the gene-carrying molecule, is put together. In biology class, the high point of the year was when we got to dissect a frog. My bench mates and I shredded our frogs muscle and skin in what can only be described as a hormone-fueled frenzy. (What we did with the frogs eyes should never, ever be recounted.)

Genetics, invented by the monk Gregor Mendel to describe the way traits are passed to the next generation (from both parents, but randomlysome dominating, some hidden), was dealt with mainly in guidance class. We endured this class, pinned under the stern gaze of a freckled, balding and dour man who perched habitually on the front edge of his desk, banging his artificial leg against it for emphasis. We thought we were there to learn about how to be adults, but discussion of the basics, like sex, was mainly forbidden; I was kicked out for putting forth the radical notion that people might want to have sex before marriage to find out if they are compatible.

Our instructor seemed to think we needed to know human genetics, but he taught it as if it were eugenics. Genetics concerns the expressions and mutations of particular inherited characteristics, embodied as genes. Eugenics proposes that people are like corn or flies, that complex human traits are passed on in the same way as the wrinkled-skin trait is among peas. Eugenics proposes we weed out our bad traits, such as impulsiveness or violent temper, while encouraging the good, such as Christian kindness or high intelligence, through selective breeding. My guidance teacher mainly warned that inbreeding is dangerous and had led, in the isolation and ignorance of the American backwoods, to whole families of drooling, feeble-minded moral degenerates. The names of these unworthies? The Kallikaks and the Jukes, whose unfortunate pairings and unacceptable children, as well as their brushes with the law, had been recorded by the Eugenics Record Office of Cold Spring Harbor, New York, in the early part of the twentieth century. Of course, by the time I took guidance, the Eugenics Record Office had long since closed in disgrace (although not before it influenced some thirty U.S. states to adopt laws regarding who was unfit to have children). The Record Office founders were soon forgotten by polite society, along with any notion that eugenics is a science.

Yet our teacher thought eugenics was an obvious extension of the work of Darwin and Mendel. He was not alone. Next door in Alberta, there were still eugenics laws on the books, long after the The high point in guidance class occurred on the last day of the last year of high school, when we were freed from it forever.

I avoided thinking about genetics/eugenics for many years, until I began to research a book on Native American origins. I was then confronted with scientists belief that one can trace a human populations movements by comparing mitochondrial DNA gathered from the living with that from the dead. Scientists doing this work assert that there are patterns of change in this DNA that are distinctive enough to show relationships of descent. This was terrain Id never traversed before. I knew that mitochondria in a cell do something that fuels each cells operationsI knew it because I looked it up in my daughters high school biology textbook. But until then Id thought that human DNA is found only in the nucleus of a cell, as part of a chromosome. I had no idea that these mitochondria are circular strings of DNA floating within the larger structure of the cell, that they also carry genes, or information, from one generation of cells to the next, just like the DNA locked in chromosomes.