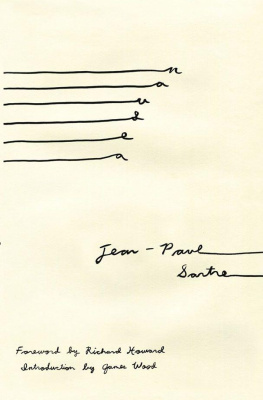

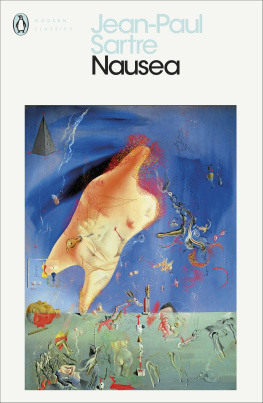

Jean-Paul Sartre - Nausea

Here you can read online Jean-Paul Sartre - Nausea full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: New Directions, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Nausea

- Author:

- Publisher:New Directions

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nausea: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Nausea" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nausea — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Nausea" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Nausea

(La Nause)

Jean-Paul Sartre

Translated from the French by Lloyd Alexander

Foreword by Richard Howard

Introduction by James Wood

A NEW DIRECTIONS PAPERBOOK

A FOREWORD TO NAUSEA

Richard Howard

When the thirty-one-year-old Jean-Paul Sartre, a refractory philosophy teacher in Le Havre (it is one thing to enjoy talking with your students and giving lectures, it is quite another to see yourself as a prof surrounded by other profs giving magisterial lectures and maintaining discipline in class: I didnt like my colleagues, I didnt like the atmosphere of the lyce), having already published an essay LImagination with Alcan in 1936, submitted his first novel Melancholia to Gallimard later that same year, it was rejected, despite a favorable readers report by Jean Paulhan; in an interview some thirty-five years later, Sartre remarked: I took this hard: I had put all of myself into a book I worked on for many years; it was myself that had been rejected, my experience that had been excluded. Sartre had begun writing what he called his factum on contingency at the age of twenty-six, and was subsequently to acknowledge influences ranging from Valry and Cline to Rilkes Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge; he was convinced of his novels worth through and beyond the prestige of its derivations.

Resubmitted to Gallimard in April 1937 with powerful recommendations from Charles Dullin and Pierre Bost, Sartres novel was at last accepted, though the title was judged inadequate, as were certain raw episodes in the textRoquentins transactions with chambermaids in the Hotel Printania, details of low life in Bouville (mudville, after all), and scenes of Roquentins past. Sartre agreed to cuts, and suggested an alternative title: The Extraordinary Adventures of Antoine Roquentin, supplemented (and contradicted) by a bande publicitaire that would confess (or exult): There are no adventures. I treasure this suggestion as the sole example I can come up with of an eighteenth-century libertine irony in Sartres entire oeuvre. This too-playful formula (after all, the work had originally been called Melancholia!) was also rejected, and finally Gaston Gallimard himself came up with a title which famously prevailed for the novel itself (and in some thirty translations the world over: how deceived we should be, as the French say when they mean disappointed, if confronted today by a novel with that original, all-too-human, sentimental or psychiatric appellation). Though Gaston Gallimards title has remained more closely identified with the author than that of any other of his fictions or plays, Sartre as well as Simone de Beauvoir had reservations about nausea, apprehensive that such title would inspire a naturalistic reading of his experimental metaphysical novel. But what actually happened is that the word somehow changed its meaning because of the novels title: capitalized and clearly in reference to the novel, Nausea no longer evokes physical malaise to the point of vomiting, but is a nickname for existential anguish.

La Nause was published the following April, and Sartres only book of short stories, Le Mur, written during the same years as the novel, was published in February 1939. It is these two works (of both Lloyd Alexander is the fortunate and gifted English translator, though I cannot resist the collegial privilege of pointing out that in a list of Annies personal stage properties on page 136, shawls, turbans, mantillas, Japanese masks, pictures of Epinal, the last item will necessarily confront the non-French reader with an enigma unless it is explained that images dpinal are not representations of a cotton-manufacturing town in NE France just south of Nancy, but old-fashioned conventionalized figures on printed fabrics, often affectionately collected and reproduced as illustrations in sentimental childrens books), and especially the novel in the readers hands, which afford Sartre his place as a decisive figure in modern fiction: within a decade of its publication La Nause became a sort of modern classic, without thereby losingin the minds of its enormous readershipits virulence, its emotional charge, its abiding fascination. This, on the one hand, because of its realistic power (Sartre was right about the effect of this particular kind of post-Zola treatment, but wrong to fear that it would damage a readers appropriate response to his essential, or rather his existential enterprise), for Nausea is indeed a primary document of the everyday life and social anxiety of the thirties; but on the other hand, in formal terms and on account of its philosophic-fictional problematics, the work marks out a new and extremely influential departure for fiction, and was immediately taken by many French critics as the index of a liberation for the French novel (of course, as Alain Robbe-Grillet has reminded us some three decades later, all novels need to be liberated: literature is its own oppressor and must be its own emancipator).

Indeed it is by such novelistic problematics (narrative ambiguity, disintegration of character, repudiation of psychology, sportive experimentation of style) that Nausea inaugurated and was followed and favored by a healthy proportion (however dubious that adjective) of the French novels of the second half of the twentieth century.

In the procession of Sartres literary works, Nausea would seem to occupy a privileged site: it is the founding work on which all subsequent texts may be said to rest, however fitfullysignificantly, this first novel has never been disowned or disestablished by its authorand it is a work of experiment and transition informing all his productions to come, even as it is retrospectively modified by them. At some thirty years distance, it is answered, complemented and opposed by The Words, which immediately upon publication was cited as Jean-Paul Sartres other most decisive literary triumph. The author himself unhesitatingly acknowledged a preference for the earlier work; in an interview with the dogged editors of the Pliade edition of Sartres novels, he remarked: Ultimately, I stand by one thing, which is Nausea.... Its the best of what Ive done.

Perhaps not incidentally, the exhaustive scholarship which Messers Contat and Ribalka have provided in their splendid edition and on which I have drawn to a very minor extent (in comparison to the documentary riches they afford) offers a diverting illumination with which to conclude these prefatory observations. A roquentin, they tell us, has as its primary meaning in the Larousse Dictionary of the Nineteenth Century: A name formerly given to songs composed of fragments of other songs and linked together as in a cento, so as to produce bizarre effects by changes in rhythm and abrupt breaks in the succession of thoughts. They note that Nausea continually refers to other ways of speaking, even as it rejects them, and that Antoine Roquentin himself appears to be a man who listens to and copies others discourse in order to reconstitute it, half seriously, half comically, in his diary. Sartre himself, they add, was familiar with this meaning of roquentin, but assured them it had had no influence on the composition of his text nor on the choice of his heros name.

INTRODUCTION

James Wood

I.

In a lecture delivered in 1945, Jean-Paul Sartre described existentialism as the attempt to draw all the consequences from a position of consistent atheism. Nausea, which appeared seven years earlier, in 1938, represents an early installment in this process of atheistical traction. It thus belongs alongside Camuss novel The Stranger, and his philosophical essay

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Nausea»

Look at similar books to Nausea. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Nausea and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.