Jean-Paul Sartre - Nausea (Penguin Modern Classics)

Here you can read online Jean-Paul Sartre - Nausea (Penguin Modern Classics) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Penguin Books Ltd, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

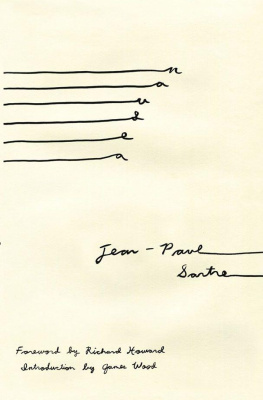

- Book:Nausea (Penguin Modern Classics)

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Books Ltd

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nausea (Penguin Modern Classics): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Nausea (Penguin Modern Classics)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nausea (Penguin Modern Classics) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Nausea (Penguin Modern Classics)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

With an Afterword by James Wood

The founder of French existentialism, JEAN-PAUL SARTRE (19051980) has had a great influence on many areas of modern thought. A writer of prodigious brilliance and originality, Sartre worked in many different genres. As a philosopher, a novelist, a dramatist, a biographer, a cultural critic and a political journalist, Sartre explored the meaning of human freedom in a century overshadowed by total war.

Born in Paris, Sartre studied philosophy and psychology at the cole Normale Suprieure, where he established a life-long intellectual partnership with Simone de Beauvoir. He subsequently taught philosophy in Le Havre and in Paris. His early masterpiece Nausea (1938) explored the themes of solitude and absurdity. A remarkable collection of short stories, The Wall (1939), further established his literary reputation. Conscripted into the French army in 1939, Sartre was captured in June 1940 and imprisoned in Stalag XIID in Trier. He soon escaped to Paris where he played an active role in the Resistance. This experience of defeat and imprisonment, escape and revolt served to push Sartre beyond the flamboyant anarchist individualism of his early writings. Being and Nothingness (1943) is an elaborate meditation on the possibility of freedom. The Age of Reason, The Reprieve and Iron in the Soul (194549) comprise the Roads to Freedom trilogy of novels, about the collective experience of war. In 1944 Sartre abandoned his career as a philosophy teacher. He was soon installed at the centre of Parisian intellectual life: editing Les Temps modernes, a literary-political review, travelling the world, quarrelling with Albert Camus, his erstwhile friend, and vigorously defending the idea of the Soviet Union against its Cold War enemies. From 1944 until 1970, when his eyesight began to fail, Sartre enjoyed an immense international reputation as the most gifted and outspoken literary intellectual of the age. In a gesture that perfectly symbolized his audacity, he refused the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1964. Fired by a passion for freedom and justice, loved and hated in his own day, Sartre stands as the authentic successor to Voltaire, Victor Hugo and mile Zola.

ROBERT BALDICK was a translator, scholar and co-editor of Penguin Classics. His translations include works by Verne, Flaubert and Radiguet, as well as a number of novels by Georges Simenon.

JAMES WOOD was born in Durham, in 1965, and educated at Jesus College, Cambridge. He is Professor of the Practice of Literary Criticism at Harvard University and a staff writer at the New Yorker magazine.

TO THE BEAVER

He is a fellow without any collective significance, barely an individual.

L. F. Cline, The Church

These notebooks were found among Antoine Roquentins papers. We are publishing them without any alteration.

The first page is undated, but we have good reason to believe that it was written a few weeks before the diary itself was started. In that case it would have been written about the beginning of January 1932, at the latest.

At that time, Antoine Roquentin, after travelling in Central Europe, North Africa, and the Far East, had been living for three years at Bouville, where he was completing his historical research on the Marquis de Rollebon.

THE EDITORS

The best thing would be to write down everything that happens from day to day. To keep a diary in order to understand. To neglect no nuances or little details, even if they seem unimportant, and above all to classify them. I must say how I see this table, the street, people, my packet of tobacco, since these are the things which have changed. I must fix the exact extent and nature of this change.

For example, there is a cardboard box which contains my bottle of ink. I ought to try to say how I saw it before and how I anything but note down carefully and in the greatest detail everything that happens.

Naturally I can no longer write anything definite about that business on Saturday and the day before yesterday I am already too far away from it; all that I can say is that in neither case was there anything people would ordinarily call an event. On Saturday the children were playing ducks and drakes, and I wanted to throw a pebble into the sea like them. At that moment I stopped, dropped the pebble and walked away. I imagine I must have looked rather bewildered, because the children laughed behind my back.

So much for the exterior. What happened inside me didnt leave any clear traces. There was something which I saw and which disgusted me, but I no longer know whether I was looking at the sea or at the pebble. It was a flat pebble, completely dry on one side, wet and muddy on the other. I held it by the edges, with my fingers wide apart to avoid getting them dirty.

The day before yesterday, it was much more complicated. There was also that series of coincidences and misunderstandings which I cant explain to myself. But Im not going to amuse myself by putting all that down on paper. Anyhow, its certain that I was frightened or experienced some other feeling of that sort. If only I knew what I was frightened of, I should already have made considerable progress.

The odd thing is that I am not at all prepared to consider myself insane, and indeed I can see quite clearly that I am not: all these changes concern objects. At least, that is what Id like to be sure about.

Perhaps it was a slight attack of insanity after all. There is no longer any trace of it left. The peculiar feelings I had the other week strike me as quite ridiculous today: I can no longer enter into them. This evening I am quite at ease, with my feet firmly on the ground. This is my room, which faces north-east. Down below is the rue des Mutils and the shunting yard of the new station. From my window I can see the red and white flame of the Rendez-vous des Cheminots at the corner of the boulevard Victor-Noir. The Paris train has just come in. People are coming out of the old station and dispersing in the streets. I can hear footsteps and voices. A lot of people are waiting for the last tram. They must make a sad little group around the gas lamp just under my window. Well, they will have to wait a few minutes more: the tram wont come before a quarter to eleven. I only hope no commercial travellers are going to come tonight: I do so want to sleep and have so much sleep to catch up on. One good night, just one, and all this business would be swept away.

A quarter to eleven: theres nothing more to fear if they were coming, they would be here already. Unless its the day for the gentleman from Rouen. He comes every week, and they keep No. 2 for him, the first-floor room with a bidet. He may still turn up; he often drinks a beer at the Rendez-vous des Cheminots before going to bed. He doesnt make too much noise. He is quite short and very neat, with a waxed black moustache and a wig. Here he is now.

Well, when I heard him coming upstairs, it gave me quite a thrill, it was so reassuring: what is there to fear from such a regular world? I think I am cured.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Nausea (Penguin Modern Classics)»

Look at similar books to Nausea (Penguin Modern Classics). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Nausea (Penguin Modern Classics) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.