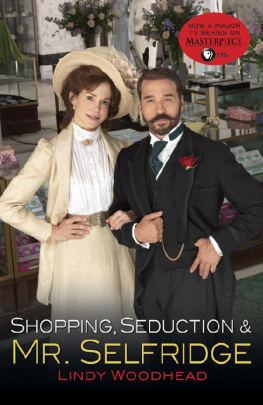

MR. SELFRIDGE

Is available on Blu-ray and DVD.

To purchase MR. SELFRIDGE,

visit shopPBS.org.

BRITISH PRAISE FOR

SHOPPING, SEDUCTION & MR. SELFRIDGE

Gripping and excellently researched.

Literary Review

Lindy Woodhead paints a colourful picture of the American who turned Edwardian England on to shopping, and who transformed shopping into a democratic sport, entertainment for the masses and a truly capitalist endeavour.

Womens Wear Daily

In this lively and compelling biography, Lindy Woodhead follows the glory years of a charismatic big spender, whose ill-advised expansion would eventually be his downfall. Her pacy narrative takes in his glamorous women, his social set, the sexing up of shopping, and seismic shifts in society.

Director

Far more than just a profile of one of the worlds great shopkeepers, Lindy Woodheads biography of Harry Gordon Selfridge provides a rich social history in a time of great change.

Spectator

Perhaps the first English shop owner to identify shopping as thrilling, sexy entertainment Lindy Woodhead tells not only the story of the rise and dramatic fall of Selfridge, the man, but also provides an enthralling description of fashion, politics, music and dance, the arts, the sciences, advertising and the use of the media.

Evening Standard

2013 Random House Trade Paperback Edition

Copyright 2007, 2008, 2012 by Lindy Woodhead

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House Trade Paperbacks, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE T RADE P APERBACKS and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in 2007 and 2008 in the United Kingdom as Shopping, Seduction & Mr Selfridge in hardcover and paperback respectively, and in a revised edition in 2012 by Profile Books, Ltd, London.

Photo credits are located on .

eISBN: 978-0-8129-8505-4

www.atrandom.com

Title-page photo of Selfridges department storefrom English Heritage

Cover design: Beverly Leung

Cover photograph: ITV 2012; photographer: John Rogers

v3.1_r1

Woman was what the shops were fighting over when they competed, it was woman whom they ensnared with the constant trap of their bargains, after stunning her with their displays.

They had aroused new desires in her flesh, they were a huge temptation to which she must fatally succumb, first of all by giving in to the purchases of a good housewife, then seduced by vanity and finally consumed.

EMILE ZOLA ,

Au Bonheur des Dames (1881)

When I die I want it said of me that I dignified and ennobled commerce.

HARRY GORDON SELFRIDGE

(18561947)

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

CONSUMING PASSIONS

T HE RISE OF THE DEPARTMENT STOREOR WHAT IN PARIS were more gracefully called les grands magasinsin the second half of the nineteenth century was a phenomenon that encompassed fashion, advertising, entertainment, emergent new technology, architecture, and, above all, seduction. These forces evolved to merge into businesses that Emile Zola astutely called the great cathedrals of shopping, and vast fortunes were made by the men who owned them as they tapped into the female passion for shopping. But arguably no one man grasped the concept of consumption as sensual entertainment better than the maverick American retailer Harry Gordon Selfridge, who opened his eponymous store on Londons Oxford Street in 1909.

In building the West Ends first fully fledged department store, he quite literally changed everything about the way Londoners shopped. His visionary, larger-than-life Edwardian building perfectly reflected the character of its founderthe only modest thing about him being his height. It was Harry Gordon Selfridge who positioned the perfume and cosmetics department immediately inside the main entrance, a move that changed the layoutand turnoverof the sales floor forevermore. Selfridge created window dressing as an art form, pioneered in-store promotions and fashion shows, and offered customer service and facilities previously unheard of in Britain. Above all, he gave his customers fun. At a time when there was no radio or television, when cinema was in its infancy, Selfridges in Oxford Street offered customers entertainment as fascinating as that at a science museum, with as much glamour as on any music-hall stage. In giving his customers a unique day out, Harry Selfridge proudly boasted that after Westminster Abbey and the Tower of London, his store was the third biggest tourist attraction in town. The public could buy much of what they needed at Selfridges, and much that they never knew they wanted until they were seduced by the tantalizing displays.

Harry Selfridge perfected the art of publicity, spending more money on advertising than any retailer of his era. A consummate showman, he himself became a celebrity at a time when there were few identifiable, exciting personalities that the public could see at close quarters. When he arrived at work, there was invariably a cluster of customers waiting to meet and greet the famous Mr. Selfridge. His ritualistic morning tour of the store, where his staff of thousands lined up anxiously by their counters in eager anticipation of a personal nod of approval from their boss, was the curtain-raiser to the daily show at Selfridgesthe only difference being that for his audience, entrance was free.

There was no shortage of shops or stores in London and many other wealthy provincial cities in Britain whenafter twenty-five years working at the celebrated store Marshall Field & Company in ChicagoSelfridge masterminded his grand plan to open in the imperial capital. The industrial transformation that had occurred in Britain had created a new spending population that was proud to show off its wealth by acquiring consumer goods, and retailers scrambled to cope with an almost insatiable demand. The new rich had large houses to equip, a prodigious number of childrennot to mention an army of servantsto dress, and their own position in society to promote. Happily for retailers, conspicuous consumption, always so crucial in defining wealth and status, had found itself a much larger market.

That fashion became big business was because of big dresses. In the 1850s, when both the young Queen Victoria and the French style icon, the Empress Eugnie, both enthusiastically embraced the new caged crinoline, clothes billowed to unprecedented proportions. Women of substance were dressed from head to toe in as much as forty yards of fabric. As well as a muslin shift and cotton or silk underwearnot to mention the ubiquitous corsetthe ensemble had hoops underneath, and at least three if not four petticoats, in layers varying from flannel through muslin to white, starched cotton. Add to this a lace fichu, bead-trimmed cape, fur or embroidered muff, hat, gloves, parasol, stockings, button boots and reticuleand consider that the entire paraphernalia was usually changed once a day and often again in the eveningand one can begin to comprehend the costs, not to mention profits, in supplying it all. As if this bonanza wasnt enough for retailers who stocked all of the above and ran vast workrooms making the finished gowns, there was the ritual of mourning the dead. This meant the whole thing all over againbut this time in black. Many a Victorian linen-drapers fortune was made merely by operating a successful mourning department, and one of the first diversifications into added-value customer services was to offer funeral facilitiesright down to supplying dyed black ostrich feathers for the horses that pulled the hearse.