W HAT a story!

I put down the last sheet of the manuscript with regret. It was like saying good-bye to a close friend. For several days I had spent my lunch hours in the office reading entranced this tale which had recently come into my possession. Even the difficulty of deciphering the tiny, close handwriting could not turn me from the sense of personal adventure as in thought I accompanied my father on his expeditions, sharing with him the hardships, seeing through his eyes the great objective, feeling with him something of the loneliness, the disillusionments and the triumphs.

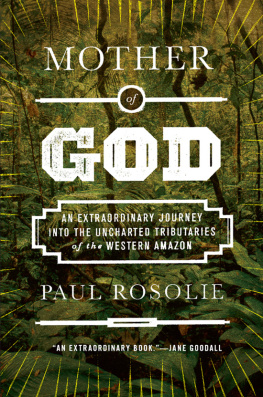

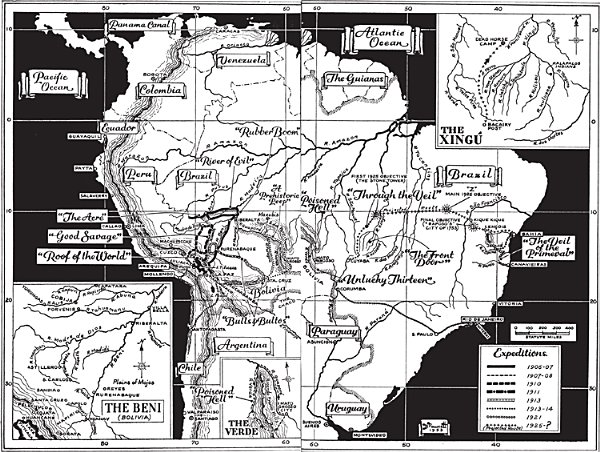

Looking from my office windows into the leaden greyness of the Peruvian coastal winter I felt the vastness of South America. Beyond the barrier of the Andes, towering up there to the east above the low, dripping ceiling of cloud, lay the enormous expanse of the wilderness, hostile and threatening, holding inviolable its secrets from all but the most daring. Rivers twisting crazily through the silent curtains of junglesluggish, muddy rivers full of death. Forests in which animal life could be heard but not seensnake-infested swampshungry, fever-haunted wildssavages ready to resist with poisoned arrows any invasion of their privacy. I knew something of itenough to enable me to follow my father vividly in the pages of that manuscript as he took me with him back into the barbarism of the Rubber Booms last years, with all its debauchery and cruelty; to the silence of unexplored frontier rivers; and, finally, in search of the lost remnants of a once mighty civilization.

The manuscript was not entirely new to me. I could recall his writing it before I came to Peru in 1924, and on occasions hearing him read out extracts from it. But it was never finished. There remained a finale to be added laterthe great climax which his last expedition should have supplied. But the forest, in allowing him a peep at its soul, claimed his life in payment. The pages he had written in the confidence of sure achievement became part of the pathetic relics of a disaster whose nature we had no means of knowing.

When evidence of death is entirely lacking it is not easy to believe that never again will a member of ones family be seen. My mother, who had in her possession the manuscript, was convinced that some day her husband and eldest son would return. It is in no way strange that she should think so. Reports of the fate of my fathers party came in one after another, some credible, some fantastic, but not one conclusive. But a belief that my father would write the climax of his own story was not the only reason for withholding the manuscript from publication. There was also the desirability of maintaining some measure of secrecy as to the supposed whereabouts of his objective, not from motives of jealousy, but because he himself, fearful of other lives being lost on his account, urged us to do everything possible to discourage rescue expeditions should his party fail to come back.

More than fifteen years had gone by since he left on that fatal expedition in Matto Grosso, and here at last was the story of all that led up to it. Previously I had not seen his work in South America in true perspective. I knew the main events, but had lacked the material necessary to enable me to assemble them in my mind into a complete whole.

You, as his only surviving son, should have all his papers, my mother had told me, when she dug out of a trunk his log books, letters and manuscript, and handed them to me. Item by item I took them to the office with me, to peruse during the long South American lunch period, for I valued those two quiet hours more for getting my own business done than for eating. It was my accustomed time for writing and study.

I finished reading the manuscript with a growing determination to publish itto carry out as far as possible my fathers object in writing it. That object was to stimulate an interest in the mystery of the sub-continent, which, if solved, might alter our whole conception of the ancient world. It was time, I felt, that the full story should be told.

But a war was on. The railroad on which I was engaged as a mechanical engineer was a war project, and shortly after I had enthusiastically begun to type the manuscript circumstances took from me much of my spare time. Perhaps it was just as well, for when a semblance of normality eventually returned I could see that the task was too involved to be merely an avocation. To prepare it required my undivided attention; so the work was not done until I quit railroading altogether.

Art would have woven the structure of a tale with the material of but a single one of the episodes related. I hesitated to release a story so top-heavy with episodes, and lacking a climaxthe great climax it should have had. But it was not an attempt to win beauty of literary expression, I reflectedit was a mans own narrative of his lifes work and adventures; artlessly written, no doubt, but a sincere record of actual happenings.

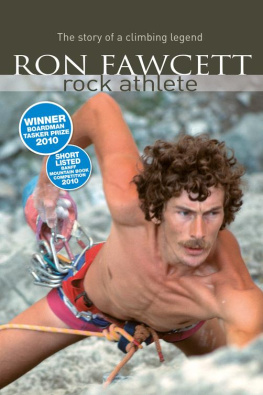

Fawcett the Dreamer, they called him. Perhaps they were right. So is any man a dreamer whose active imagination pictures the possibilities of discovery beyond the bounds of accepted scientific knowledge. It is the dreamer who is the investigator, and the investigator who becomes the pioneer. But he was also a practical mana man who in his time excelled in soldiering, in engineering and in sport. His pen drawings were accepted by the Royal Academy. He played cricket for his county. It is not to be wondered at that the young artillery officer who in his twenties built singlehanded two successful racing yachts, patented the Icthoid Curve which added knots to a cutters speedand was offered a position as design consultant with an eminent firm of yacht builders, should later achieve outstanding success in the difficult and venturesome delimitation of frontiers which in the great Rubber madness were bloodily contested by three countries. True, he dreamed; but his dreams were built upon reason, and he was not the man to shirk the effort to turn theory into fact.