SREN KIERKEGAARD

First published in Denmark under the title

SAK. Sren Aabye Kierkegaard, En biografi by Joakim Garff

Copyright 2000 by G.E.C. Gads Forlag. Aktieselskabet af 1994, Copenhagen

Published by agreement with Leonhardt & Hier Literary Agency, Copenhagen

English translation copyright 2005 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock,

Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Third printing, and first paperback printing, 2007

Paperback ISBN-13: 978-0-691-12788-0

Paperback ISBN-10: 0-691-12788-3

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows

Garff, Joakim, 1960

[SAK. English]

Sren Kierkegaard : a biography / Joakim Garff; translated by Bruce H. Kirmmse.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

ISBN 0-691-09165-X (cl : alk. paper)

1. Kierkegaard, Sren, 18131855. 2. PhilosophersDenmarkBiography. I. Title.

B4376.G28 2005

198.9dc22

[B] 2004044525

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book was translated with the kind financial support of the Danish Literature Centre, the Gads Foundation, the Royal Danish Embassy in Washington, D.C., and the Charles Lacy Lockert Fund of Princeton University Press.

This book has been composed in Bembo typeface

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4

CONTENTS

Poul Martin Mller |

The Aesthetic Is Above All My Element |

Stages on Lifes Way |

The Press: The Governments Filth Machine |

The Sealed Letter to Mr. and Mrs. Schlegel |

Part Five |

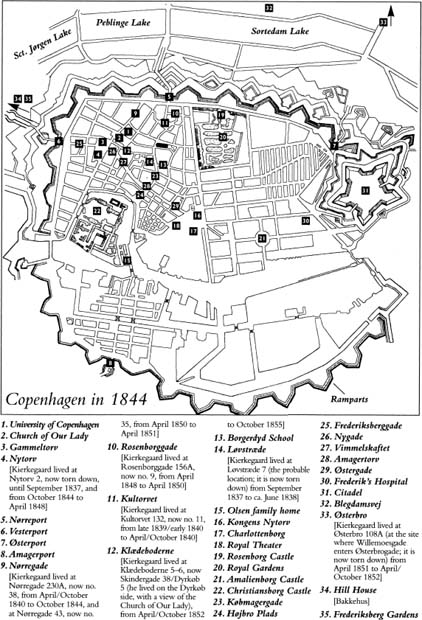

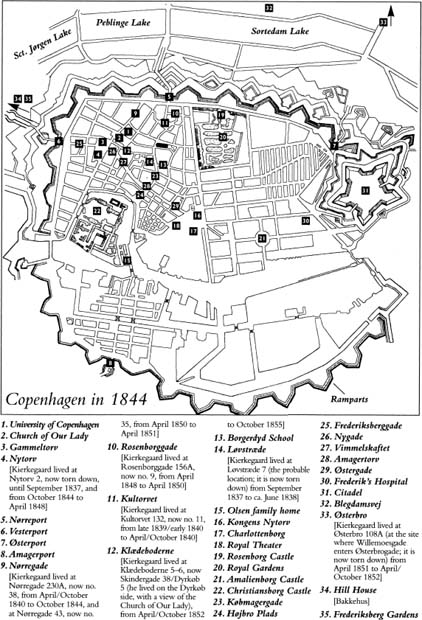

Map 1. Copenhagen in 1844.

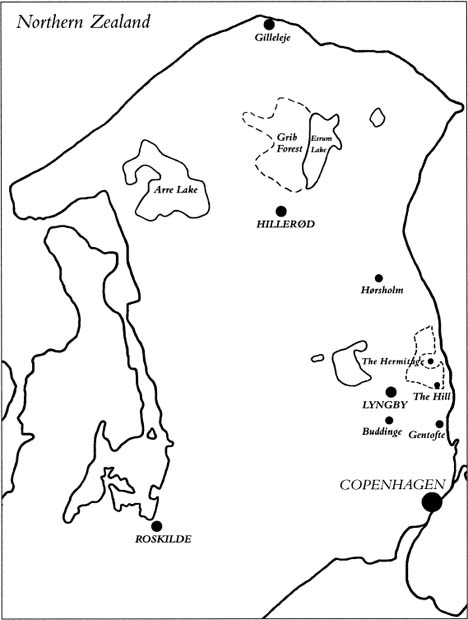

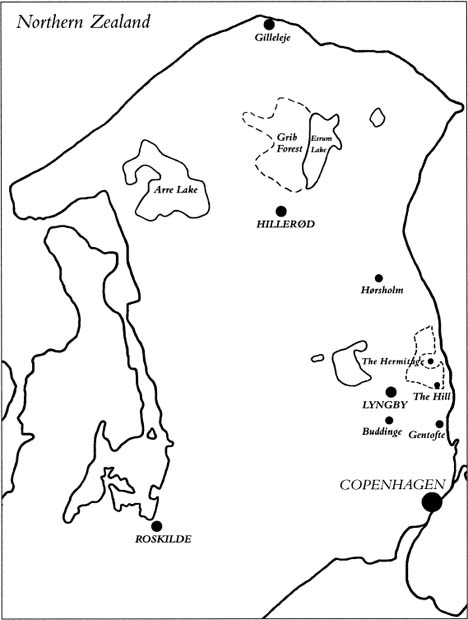

Map 2. Northern Zealand.

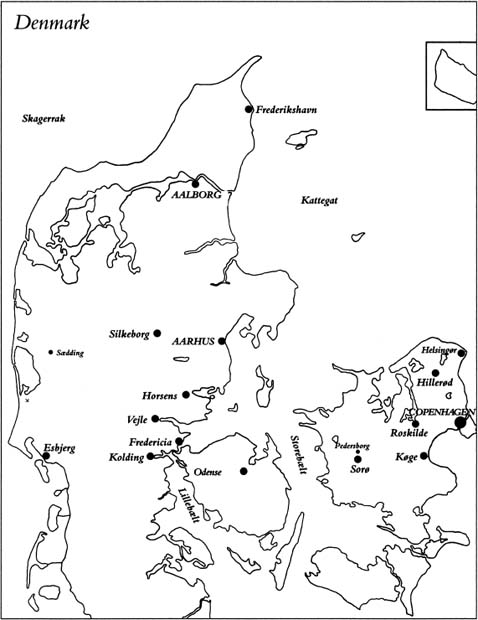

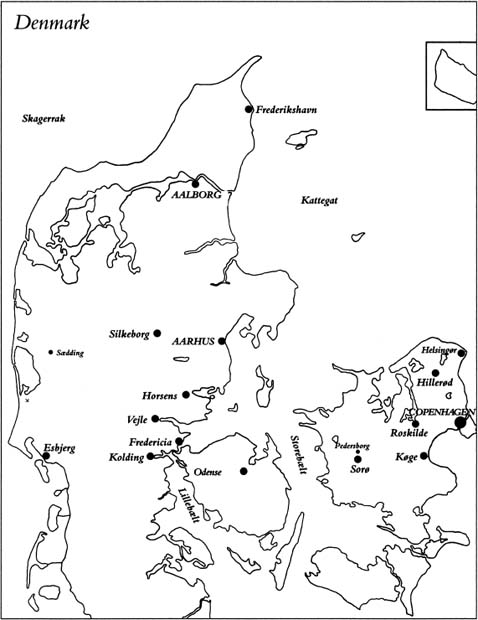

Map 3. Denmark.

PREFACE

BISHOP MARTENSEN was in his official residence, standing slightly concealed behind a curtain. The niche by the window provided an excellent view across the square adjacent to the Church of Our Lady, with the Metropolitan School in the background, the University of Copenhagen on the left, and the Church of Our Lady itself on the right. It was Sunday, November 18, 1855, just before two oclock in the afternoon. All at once a crowd of people dressed in black practically burst from the church, gathering at first in small groups, then disappearing in every direction.

A couple of hours later the episcopal pen, full of indignation, scratched its way across the pages of a letter to Martensens old pupil and friend of many years standing, Ludvig Gude, who was a pastor in Hunseby on the island of Lolland: Today, after a service at the Church of Our Lady, Kierkegaard was buried; there was a large cortege of mourners (in grand style, how ironic!). We have scarcely seen the equal of the tactlessness shown by the family in having him buried on a Sunday, between two religious services, from the nations most important church. It could not be prevented by law, however, although it could have been prevented by proper conduct, which, however, Tryde lacked here as he does everywhere it is required. Kierkegaards brother spoke at the church (as a brother, not as a pastor). At this point I do not know anything at all about what he said and how he said it. The newspapers will soon be running a spate of these burial stories. I understand the cortege was composed primarily of young people and a large number of obscure personages. As far as is known, there were no dignitaries present.

Inside the coffinreportedly quite a small onethat was being driven out to the family burial plot that November day lay the corpse of a person who over the years had become so impossible that now, after his death, it was really not possible to put him anywhere. For where in the world could one get rid of a dead man who had carried on a one-man theological revolution during the final years of his life, calling the pastors cannibals, monkeys, nincompoops, and other crazy epithets? What sense did it make to give such a person a Christian burial in consecrated ground? That this same person also left behind a body of writing whose breadth, originality, and significance was unparalleled in his times did not, of course, make the situation any less painful.

When Martensen had almost finished writing his letter to Gude, he received word of a commotion at Assistens Cemetery, and as though he were a journalist sending a live report, he continued his letter with piquant indignation: I have just learned that there was a great scandal at the grave; after Tryde had cast earth upon the grave, a son of Kierkegaards sister, a student named Lund, stepped forth with The Moment and the New Testament as a witness for the truth against the Church, which had buried Sren Kierkegaard for money, et cetera. I still have not been informed about this through official channels, but it has caused great offense, which in my view must be met with serious measures.

The rumor that reached the episcopal residence in such haste was true, and less than a day later the scandalous episode was in almost all the Copenhagen daily newspapers. Thus the morning edition of Berlingske Tidende sketched the course of events point by point, and its evening edition carried a summary of the eulogy that the deceaseds elder brother, Peter Christian Kierkegaard, had given in the church. That same Monday Flyve-Posten and Fdrelandet also rushed into print with news reports and contributions to the debate about possible malfeasance by the official in charge, and a couple of days later Morgenposten trumpeted: Scarcely was a man who declared that he was not an official Christian dead before the official Church seized his defenseless corpse and made off with it.

Naturally, as head of the Church, Martensen could not just sit with his hands folded as a mere witness to the fracas. Yet he would not speak out publiclyit was too risky. In his official capacity he took immediate action and demanded that Archdeacon Tryde provide a written account of what had taken place. From this account we learn that the interment had begun with the usual burial hymn, Who Knows How Near to Me My Death May Be, after which Peter Christian Kierkegaard had spoken eloquently and very appropriately. After another hymn the coffin was removed from the church and taken by carriage to Assistens Cemetery, where Tryde carried out the casting on of earth. This was hardly completed before Henrik Lund, a young physician, stepped forward and began to speak despite Trydes protestations and the presence of police officers who had been stationed at the cemetery for the days events. According to Tryde, Lund addressed the assembly, consisting primarily of middle-class people and numbering close to a thousand. He began by emphasizing his close relationship to his late uncle, then explained his uncles hostility to official Christianity, and finally read several passages from Kierkegaards last writings and from the Revelation of Saint John.

Next page