Copyright 2014 by Adam Tanner.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs, a Member of the Perseus Books Group.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the US by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Book design by Cynthia Young

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tanner, Adam.

What stays in Vegas : the world of personal datalifeblood of big businessand the end of privacy as we know it / Adam Tanner.First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61039-419-2 (e-book)

1. Ceasars EntertainmentCase studies. 2. CasinosNevadaLas VegasCustomer servicesCase studies. 3. Consumer profilingUnited States. 4. Business intelligenceUnited States. 5. Privacy, Right ofUnited States. I. Title.

HV6711.T36 2014

338.7'617950973dc23

2014019481

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Celia, Clarissa, and Adrian

CONTENTS

The Bad Ol Days

In 1988, I involuntarily became the subject of old-fashioned data gathering. Spies followed me around Communist East Germany and recorded my every move. That year I was visiting Dresden, the great Baroque art capital that had suffered widespread destruction from the massive Allied firebombing in World War II. Even decades after the war, some of the citys ornate buildings, including the Royal Palace, still lay in rubble. East Germanys government prided itself on operating an especially efficient Ministry of State Security, the Stasi, to monitor suspicious activities and guard against potential enemies. The Stasi mobilized their forces for my arrival, and agents made a concerted effort to learn everything they could about me.

I was researching the Frommers travel guide Eastern Europe and Yugoslavia on $25 a Day, and I spent my days visiting hotels, restaurants, and museums, as well as puzzling out how to do things such as buy train tickets when lines snaked out the station door. Communism was crumbling during these years, yet the secret police continued their dedicated vigilance. Future Russian President Vladimir Putin served in Dresden during that time as a junior KGB spy.

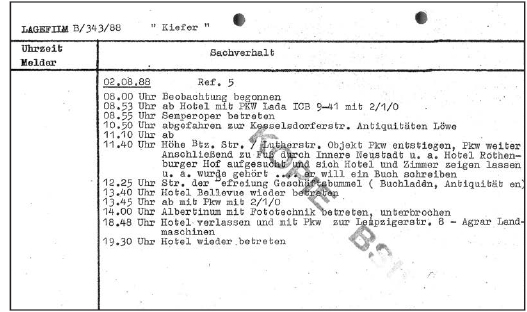

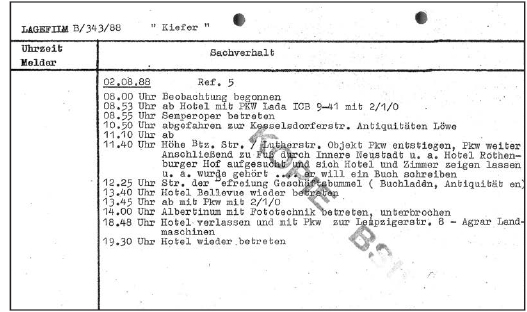

On August 2, a mild day with temperatures mostly in the sixties, I strolled around the Semper Opera, a nineteenth-century structure gutted in the bombing and reopened forty years later, in 1985. The local authorities kept a close watch. Stasi Major Hartmann oversaw a team of ten counterespionage comrade observers. They monitored my movements. Agents kept a minute-by-minute log, supplementing their efforts with surreptitious photographs. I was code-named Kiefer (Pine Tree), perhaps because I am tall. If they were hoping to catch me sneaking off to the homes of dissidents or photographing military installations, they were disappointed; I stuck closely to my guidebook checklist.

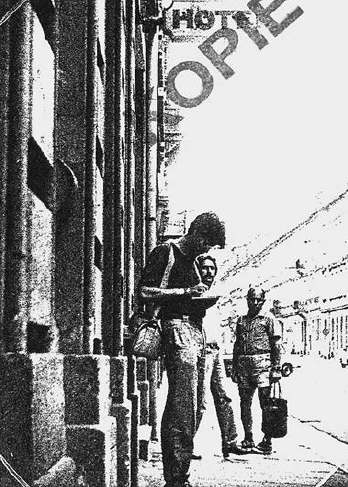

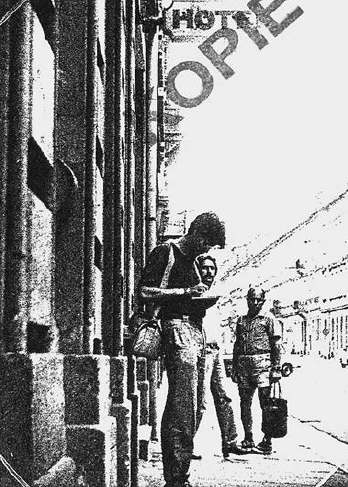

Here, Tanner, Adam, is interested in the exterior of the Semper Opera, a caption for one of the photographs reads, noting the time as 10:35 a.m. During his stop on Theaterplatz, he did not take any photographs, although he did have photographic equipment (tripod, camera bag). He made only written notes in a notebook.

As I planned my next stop, I studied a city map for a few minutes, then asked for directions. From afar, an agent snapped a photo as that random citizen, his finger upon his chin in contemplation, answered the question. The Stasi agents pondered what to do about the man amid suspicions that anyone I encountered could possibly be a covert collaborator. In the end, they did nothing. The man went off in the direction of the service building of the Semper Opera, the file recorded. He was not followed.

Secret Stasi overview of the days monitoring of Kiefer in Dresden on August 2, 1988. Source: Germanys Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Archives.

Eventually I found my destination, the former Schlachthof Fnf, where American writer Kurt Vonnegut survived the February 1945 firebombing described in his novel Slaughterhouse-Five. I stopped by the entrance of what had become a state agricultural institute and asked the guard about the buildings past. Was this the former slaughterhouse? Reading about the unscheduled inquiry some weeks later, a Stasi official grew alarmed. Likely he was not aware of the sites literary significance.

We request gathering of information on the reason for such a visit, wrote Lieutenant-Colonel Wenzel. Did he have state permission to visit?... What knowledge of German language did he show, were agreements for further contacts reached? The Stasi dispatched an agent to find out by interviewing the duty guard and researching the building. The USA citizen spoke broken but intelligible German, the follow-up report found, citing the guard.

Secret police also ordered a follow-up analysis to unravel the mystery as to why I had stopped at a local budget hotel, spoken to the clerk, popped into a room, and then quickly left. That visit struck my covert minders as highly irregular. East Germany and the Soviet Union required Western tourists to prebook hotels through the state tourism agency. Since the agency vouched for the quality of the establishment, why would anyone need to review a hotel room? Who would doubt the good word of the German Democratic Republic? The Stasi dispatched an agent to question receptionist Karin Zickmantel. She gave my German-language speaking ability a better grade (good) and explained that I had visited Room 19 on the first floor. The Stasi decided we had not hatched a conspiracy.

The following year, the Berlin Wall fell. After allowing citizens free access to the West and its myriad of choices, East Germany and its vast secret police apparatus quickly collapsed. Reunified Germany opened the Stasi files to those who had come under surveillance. More than a decade after my visit to Dresden I obtained my fifty-page dossier and learned the details of the Stasis efforts to track me across the city.

Covert Stasi photo of the author taking notes in front of a hotel. Source: Germanys Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Archives.

Truth be told, for all their diligence, the Stasi did not really learn much. In the Internet era, thanks to meticulous data gathering from both public documents and commercial records, companies today know far more about typical consumers than the feared East German secret police recorded about me. Through public records, private firms know where you live and have lived, which neighbors live near you, your relatives, what property you own, what crimes you have committed. They know your age and telephone numbers. They can research your shopping habits and hobbies, and determine favorite Internet sites. Sometimes they know your ailments, even, perhaps, if you take Viagra. They might know where you are at any time through smart phone apps and GPS locators. The aggregation of data makes finding out previously obscure information easy. All these years later, an Internet search quickly finds the home address and phone of the very same German hotel clerk who had to explain my visit to Stasi agents in 1988.

Next page

![Terence Craig and Mary E. Ludloff - Privacy and big data: [the players, regulators, and stakeholders]](/uploads/posts/book/229294/thumbs/terence-craig-and-mary-e-ludloff-privacy-and-big.jpg)