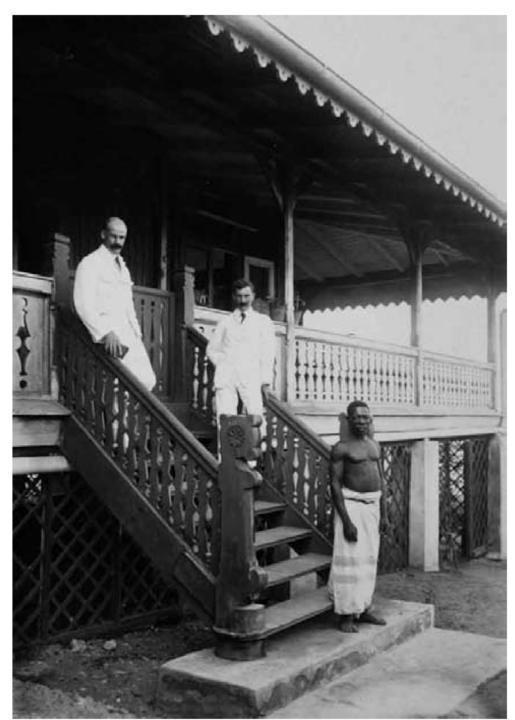

William A. Cadbury, Joseph Burtt, and an unidentified African man in Luanda, January agog. Photograph in the Cadbury Papers 308, Cadbury Research Library, Special Collections, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK.

Catherine Higgs

FIGURES

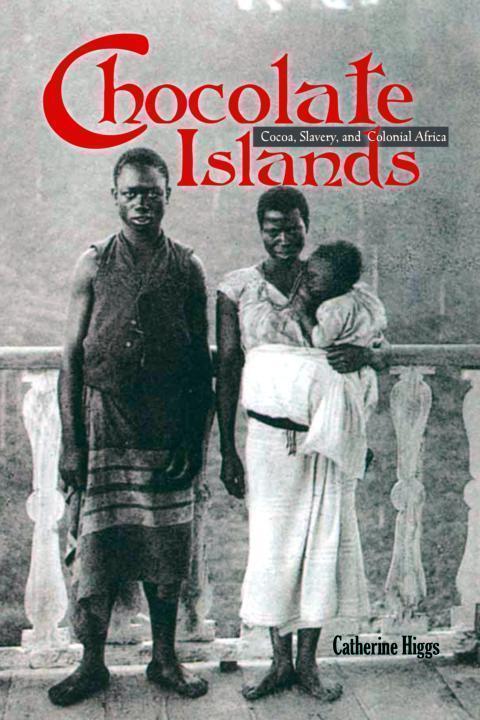

Frontispiece. WilliamA. Cadbury, Joseph Burtt, and an unidentified African man in Luanda, January lgog

i. William Adlington Cadbury, c.1910 15

2. Customs house bridge, Sao Tome City 27

3. The first baron of Agua Ize 29

4.Workers at a dependencia of Agua Ize rota, Sao Tome, early 1900s 31

5. Cocoa-drying tables 32

6. Two Sao Tomean women 35

7. Angolan servical couple, Sao Tome, c. 1907 38

8. Model housing for workers, Boa Entrada rota 40

9. Henry Woodd Nevinson in 1901 41

1o. Hospital on Agua Ize rota 44

11. Cape Verdean workers on Principe, c. 1907 49

12. Angolares' houses, Sao Tome, c. 1810 54

13. Principe-view of the bay and city 57

14. Santo Antonio, Principe 63

15.Luanda-partial view of the lower city and the African quarter, c. 1906 72

16. Afro-Portuguese elites, Benguela, c. 1905 77

IT D. Carlos I Hospital, Benguela, c. 1902 80

18. Boer (Afrikaner) transport riders, Mocamedes, c. 19o8 81

19. View of Catumbela, c. 1904 83

20. Governor-general's palace, Luanda, c. 19o6 93

21. View of Novo Redondo, c. 1904 95

22. Group of Africans and two Europeans at Benguela, c. 1905 97

23. Born Jesus fazenda on the Cuanza River, c. 19o4 108

24. Lourenco Marques, Mozambique 117

25. Alfredo Augusto Freire de Andrade, c. 19io 122

26. African miners, Witwatersrand, Transvaal Colony 126

27. Simmer and Jack Mine, Witwatersrand 127

28. Living quarters for Chinese miners 129

29. Informal housing for African miners, Johannesburg 130

30. Francisco Mantero in an undated photograph 140

31. Directors of Cadbury Brothers Limited, 1921 161

32. Joseph Burtt in the late 1920s 163

MAPS

1. Joseph Burtt's map of Sao Tome, 1905 34

2. Joseph Burtt's map of Principe, 1905 65

3. Angola, c. 1910 70

4. Joseph Burtt's map of his route from Benguela to Kavungu, 19o6 99

5. Colonial Africa, 1914 154

This book is about an Englishman's journey through Africa in the first decade of the twentieth century, undertaken as European colonial powers were tightening their grip on the continent. The traveler's name was Joseph Burtt. He had been hired by William A. Cadbury on behalf of the British chocolate firm Cadbury Brothers Limited to determine-in response to an emerging international controversy-if slaves had harvested the cocoa the company was purchasing from the Portuguese West African colony of Sao Tome and Principe.

Burtt's voyage took him from innocence and credulity to outrage and activism. Between June 1905 and March 1907, he traveled to the islands of Sao Tome and Principe, then south along the coast to the large Portuguese colony of Angola, to Mozambique in Portuguese East Africa, and to the Transvaal Colony in British southern Africa. Through his eyes, we learn about the often complacent British and Portuguese attitudes toward work, slavery, race, and imperialism in the early twentieth century. He visited agricultural estates-rotas on Sao Tome and Principe and fazendas in Angola. He talked to diplomats, journalists, and European and African businesspeople, and he traced the slave route through Angola's interior. He conferred with mine owners in the Transvaal and colonial officials in Mozambique, which supplied most of the labor for the Transvaal's mines. He was not the first man to make such a trip; readers interested in the broader literature into which this narrative of his experiences fits may wish to read `A Note on Sources" at the end of this book.

Burtt wrote a stream of letters to Cadbury recording what he saw and whom he met. He was not a flawless observer, but this should not surprise us, living as we do in an age that has long abandoned the pretense of objectivity. What Burtt wrote prompted Cadbury Brothers Limited to seek alternate sources of cocoa. The report he prepared summarizing his observations was submitted to the British and the Portuguese governments, and it helped reform the recruitment and treatment of laborers. Joseph Burtt was no casual visitor to Africa: he traveled with a purpose, and what he saw and what he did mattered. A century later, his journey echoes in the human rights organizations of our own day, which seek to expose the sometimes oppressive conditions under which workers still produce our foodstuffs. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the observations of this "big, innocent-looking man," by turns idealistic, naive, perceptive, and too often racist, help us understand the cultural blindness of those who sought to improve the lot of African workers. Yet help to improve it, as the following story demonstrates, he did.'

I am grateful to the many librarians, archivists, colleagues, and friends who have made this book possible. Dorothy Woodson, curator of the African Collection at Yale University, gave me access to the collection of James Duffy's papers donated by his widow in 2000. They restored to the archival record the set of letters Joseph Burtt wrote to William Cadbury from Africa between 1905 and 1907. Copies of the letters have been deposited in the Cadbury Research Library, Special Collections, at the University of Birmingham, where Helen Fisher and Philippa Bassett assisted me. Sarah Foden gave me access to the small archive still maintained by Cadbury Information Services (now partofKraftFoods). Two summer Professional Development Awards from the University of Tennessee funded my 2002 visit to Birmingham (Ithank IsabelHackettforherkindhospitality) and my 2003 visit to Sao Tome. I am grateful to Augusto Nascimento for introducing me to the staff at the Arquivo Hist6rico de Sao Tome and Principe and helping me negotiate the archive at a moment when I was just learning Portuguese. Nascimento and Eugenia Rodrigues (both of the Instituto de Investigacao Cientifica Tropical [IICT]) also graciously hosted me in Lisbon. A 2004 grant from the Luso-American Foundation funded a summer of research at the Biblioteca Nacional in Lisbon. I owe a special debt of gratitude to Helena Grego and Cristina Matias of the Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, who in 2006 kindly helped me track down numerous references. My debt to Gerhard Seibert of the Centro de Estudos Africanos (ISCTE-IUL) is considerable. Among many favors over the years, he read this manuscript and introduced me to the great-grandson of Francisco Mantero, who shares his name. I thank Kate Burlingham for her research assistance at the Arquivo Hist6rico Nacional de Angola, as well as the librarians and archivists at the Rhodes House Library at Oxford University; the Biblioteca Nacional, the Arquivo Hist6rico Ultramarino, and the Arquivo Hist6rico Diplomatico in Lisbon; and the Arquivo Hist6rico de Mocambique in Maputo.