Clarion Books

215 Park Avenue South

New York, NY 10003

Copyright 2003 by Jim Murphy

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Murphy, Jim

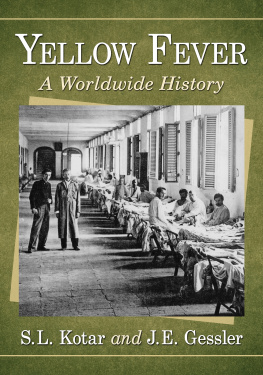

An American plague : the true and terrifying story of the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 / by Jim Murphy,

p, cm.

1. Yellow feverPennsylvaniaPhiladelphiaHistory18th century Juvenile literature. [1. Yellow feverPennsylvaniaPhiladelphiaHistory18th century. 2. PennsylvaniaHistory17751865.] 1. Title.

RA644.Y4 M875 2003

614.5'41'097481109033dc21 2002151355

ISBN 978-0-395-77608-7 hardcover

eISBN 978-0-547-53285-1

v1.0914

For Mike and Benmy wonderful, at-home germ machines. This ones for you!

With love, Dad

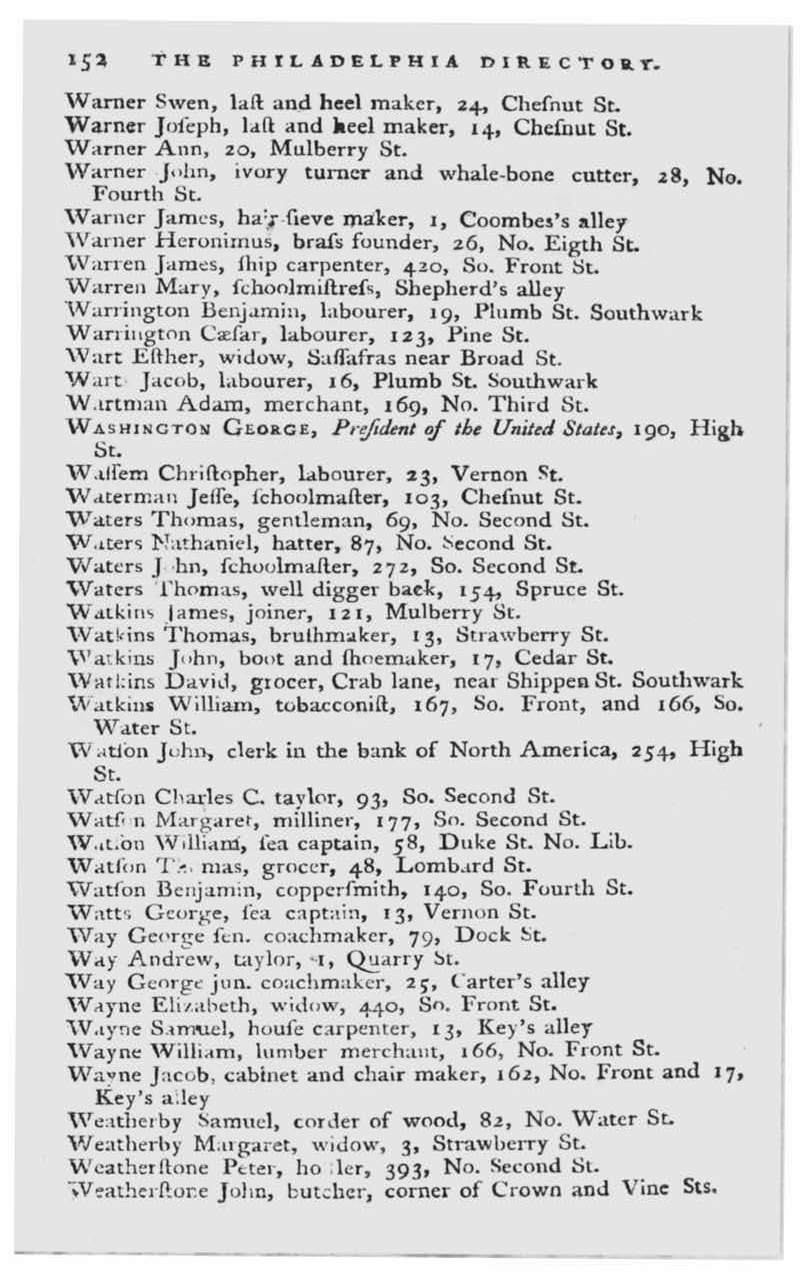

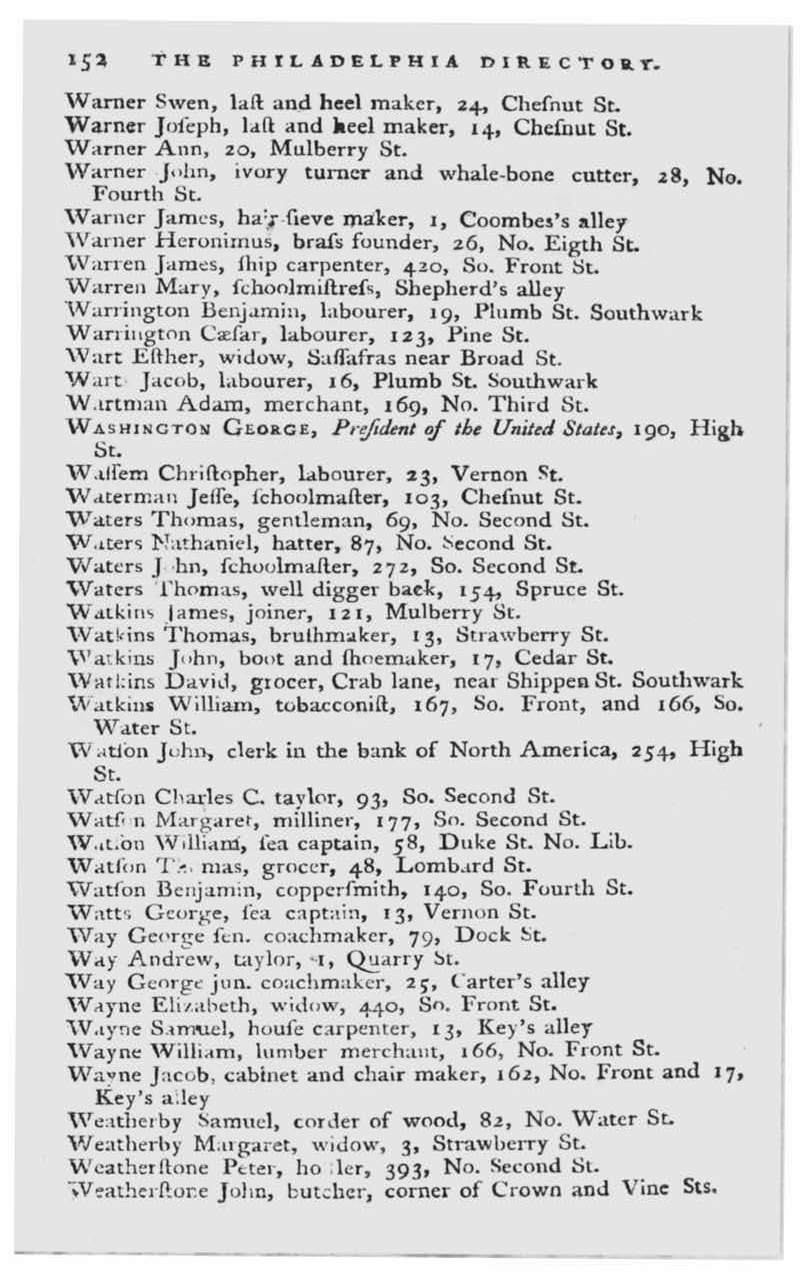

From James Hardies Philadelphia Directory and Register,

1793. (T HE L IBRARY C OMPANY OF P HILADELPHIA )

CHAPTER ONE

No One Noticed

About this time, this destroying scourge, the malignant fever, crept in among us.

M ATHEW C AREY . N OVEMBER 1793

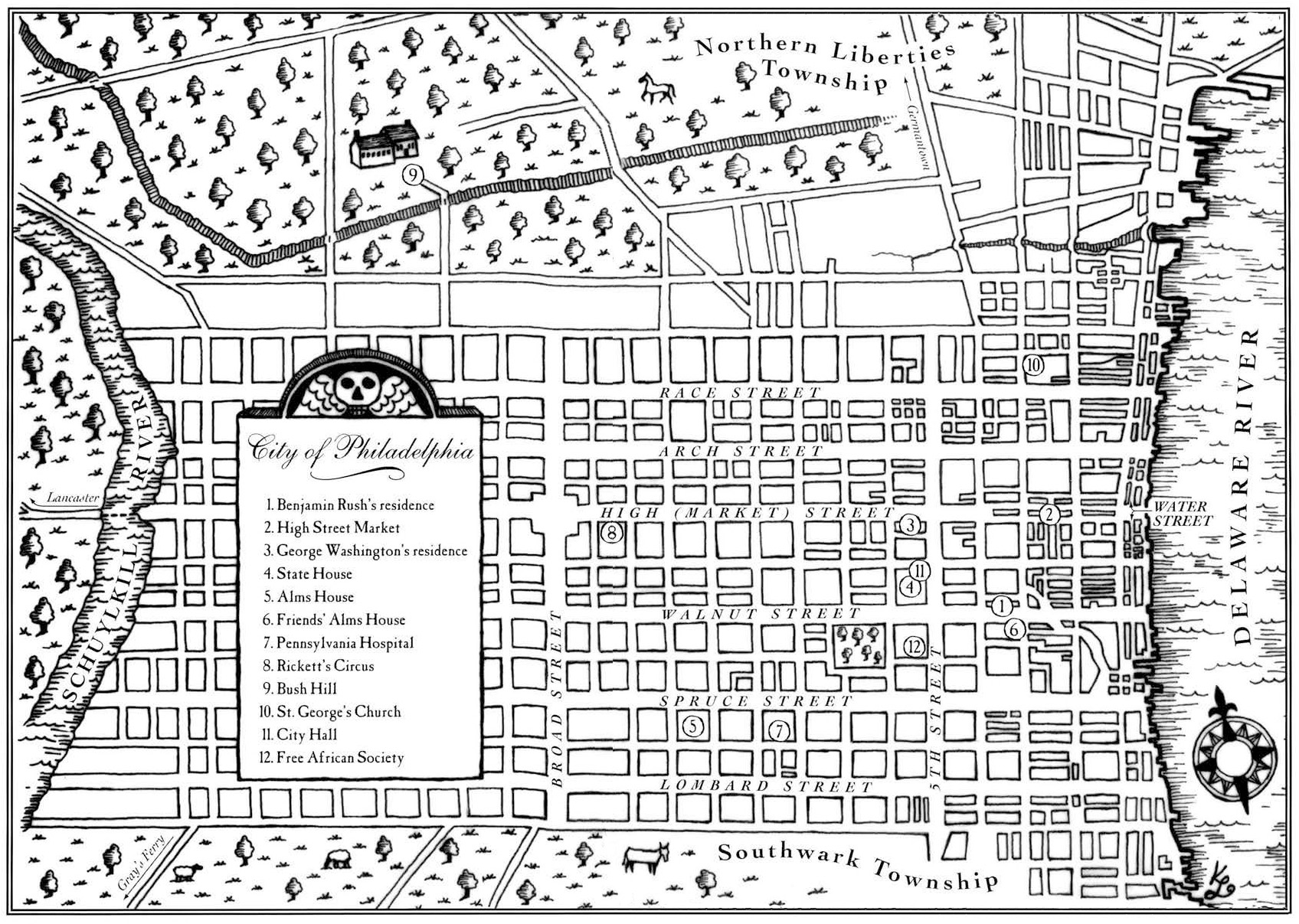

Saturday, August 3, 1793. The sun came up, as it had every day since the end of May, bright, hot, and unrelenting. The swamps and marshes south of Philadelphia had already lost a great deal of water to the intense heat, while the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers had receded to reveal long stretches of their muddy, root-choked banks. Dead fish and gooey vegetable matter were exposed and rotted, while swarms of insects droned in the heavy, humid air.

In Philadelphia itself an increasing number of cats were dropping dead every day, attracting, one Philadelphian complained, an amazing number of flies and other insects. Mosquitoes were everywhere, though their high-pitched whirring was particularly loud near rain barrels, gutters, and open sewers.

These sewers, called sinks, were particularly ripe this year. Most streets in the city were unpaved and had no system of covered sewers and pipes to channel water away from buildings. Instead, deep holes were dug at various street corners to collect runoff water and anything else that might be washed along. Dead animals were routinely tossed into this soup, where everything decayed and sent up noxious bubbles to foul the air.

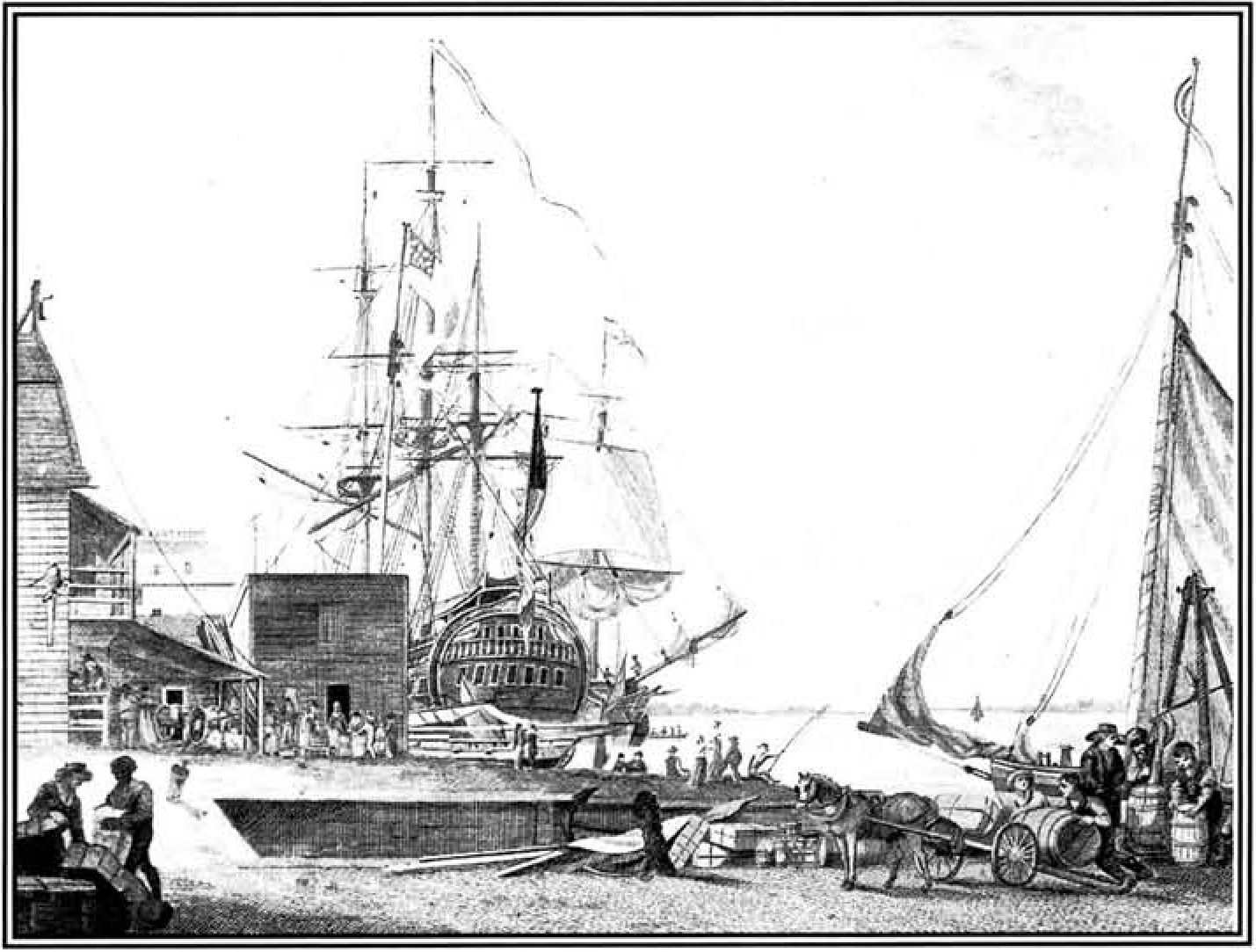

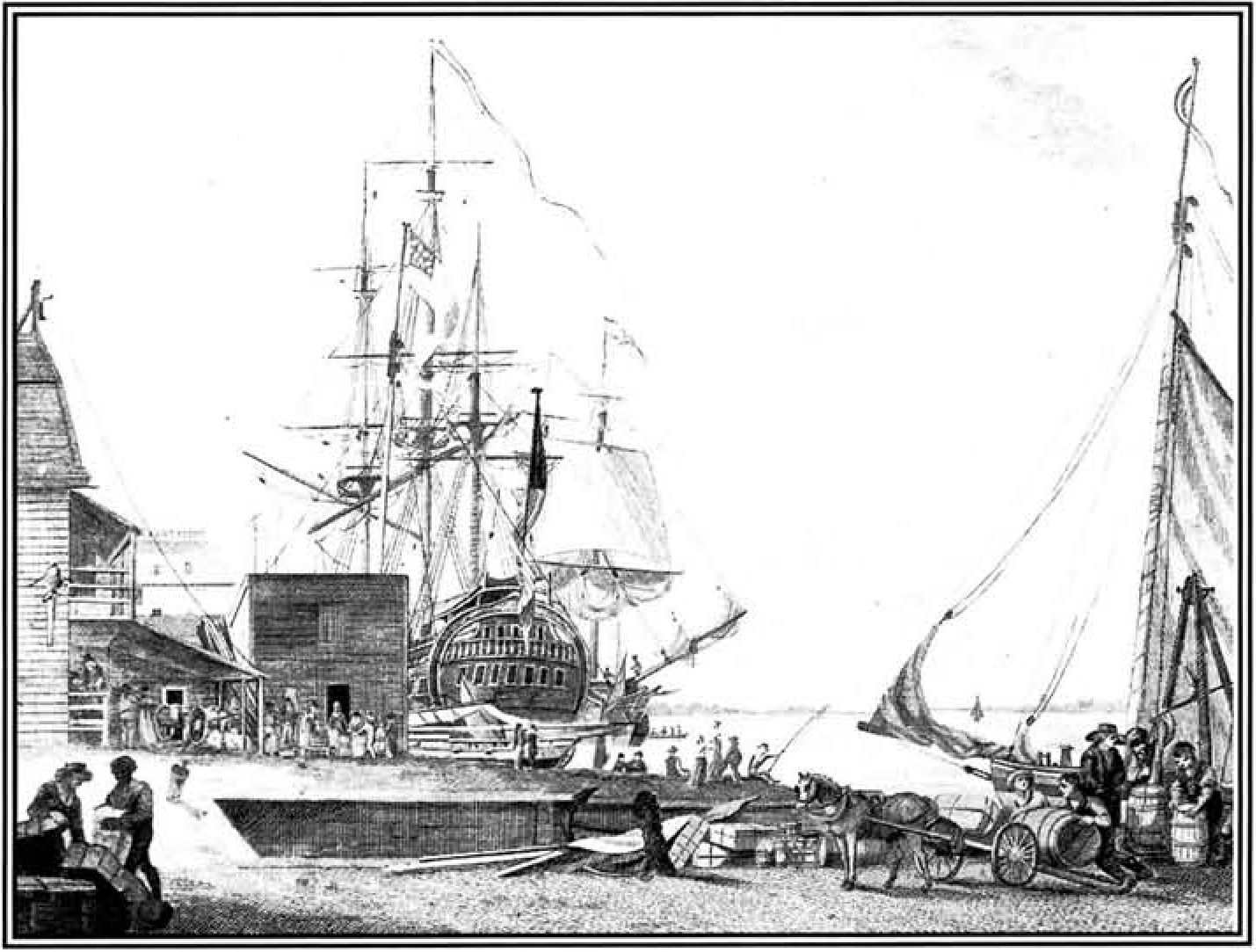

Down along the docks lining the Delaware, cargo was being loaded onto ships that would sail to New York, Boston, and other distant ports. The hard work of hoisting heavy casks into the hold was accompanied by the stevedores usual grunts and muttered oaths.

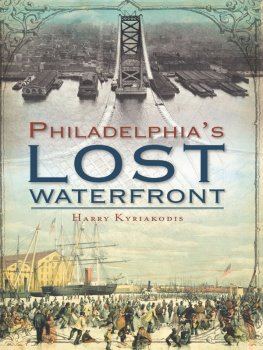

The ferryboat (right) from Camden, New Jersey, has just arrived at the busy Arch Street dock. (T HE H ISTORICAL S OCIETY OF P ENNSYLVANIA )

The men laboring near Water Street had particular reason to curse. The sloop Amelia from Santo Domingo had anchored with a cargo of coffee, which had spoiled during the voyage. The bad coffee was dumped on Balls Wharf, where it putrefied in the sun and sent out a powerful odor that could be smelled over a quarter mile away. Benjamin Rush, one of Philadelphias most celebrated doctors and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, lived three long blocks from Balls Wharf, but he recalled that the coffee stank to the great annoyance of the whole neighborhood.

Despite the stench, the streets nearby were crowded with people that morningship owners and their captains talking seriously, shouting children darting between wagons or climbing on crates and barrels, well-dressed men and women out for a stroll, servants and slaves hurrying from one chore to the next. Philadelphia was then the largest city in North America, with nearly 51,000 inhabitants; those who didnt absolutely have to be indoors working had escaped to the open air to seek relief from the sweltering heat.

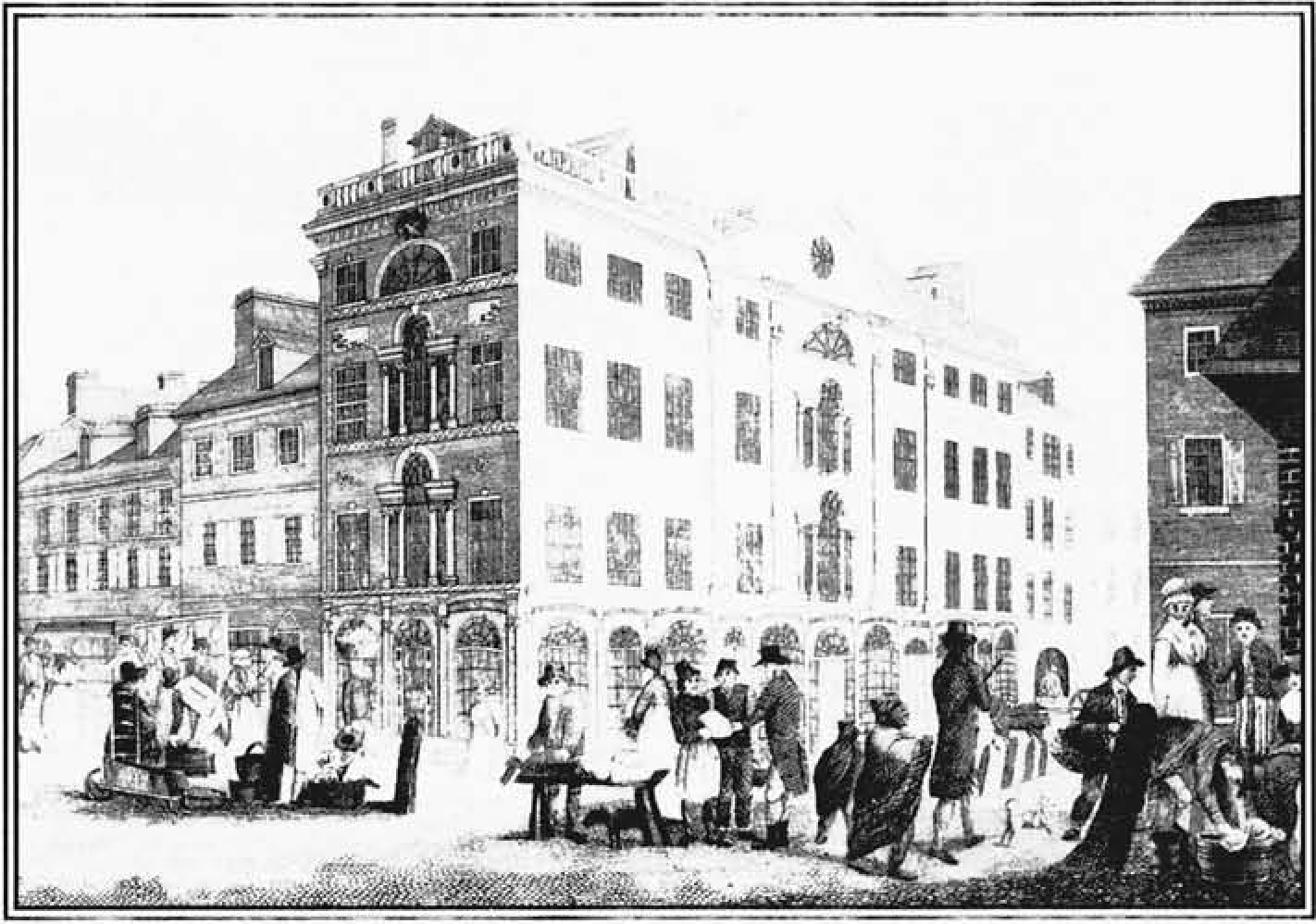

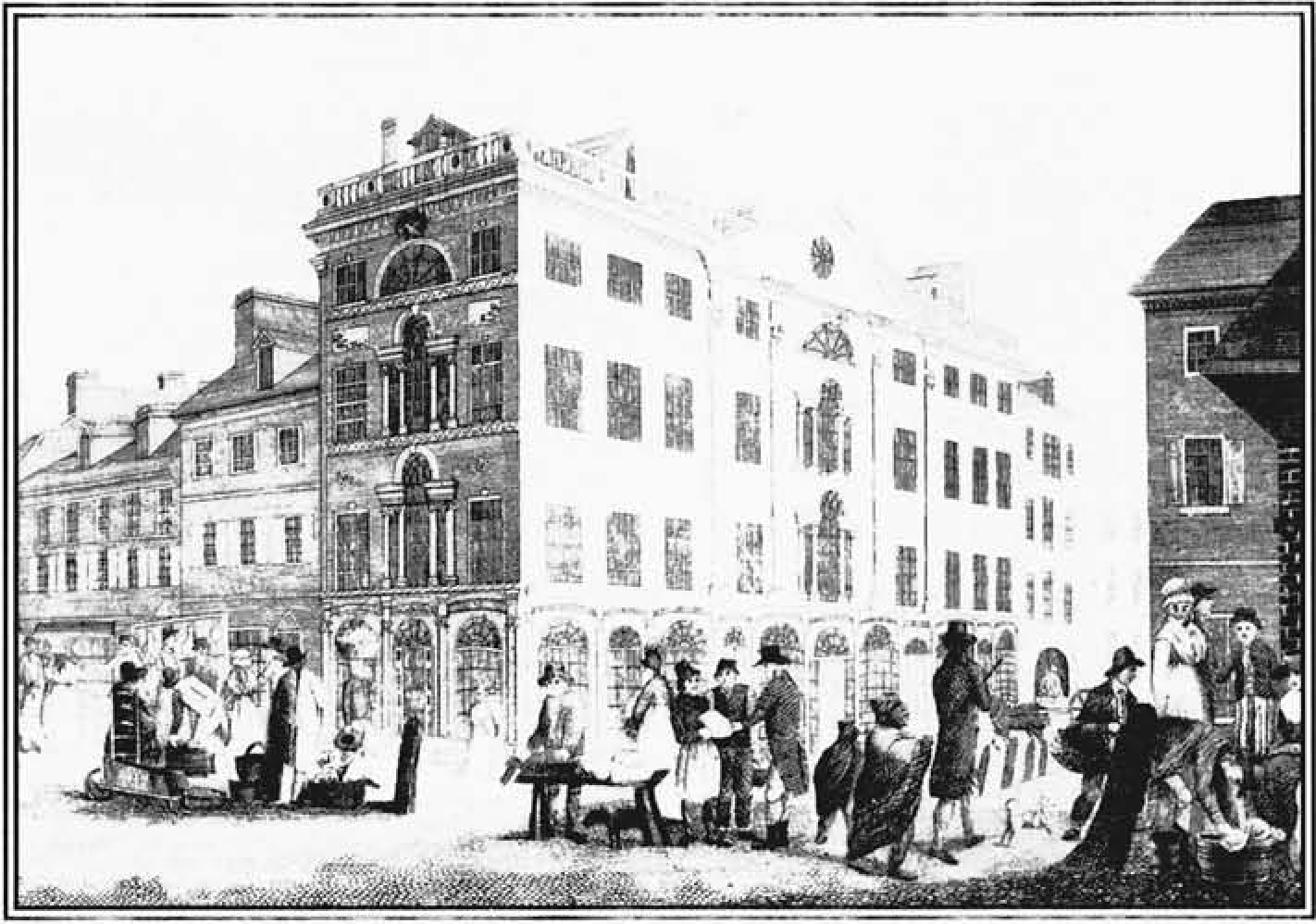

Many of them stopped at one of the citys 415 shops, whose doors and windows were wide open to let in light and any hint of a cooling breeze. The rest continued along, headed for the market on High Street.

Here three city blocks were crowded with vendors calling their wares while eager shoppers studied merchandise or haggled over weights and prices. Horse-drawn wagons clattered up and down the cobblestone street, bringing in more fresh vegetables, squawking chickens, and squealing pigs. People commented on the stench from Balls Wharf, but the markets own ripe blend of odorsof roasting meats, strong cheeses, days-old sheep and cow guts, dried blood, and horse manuretended to overwhelm all others.

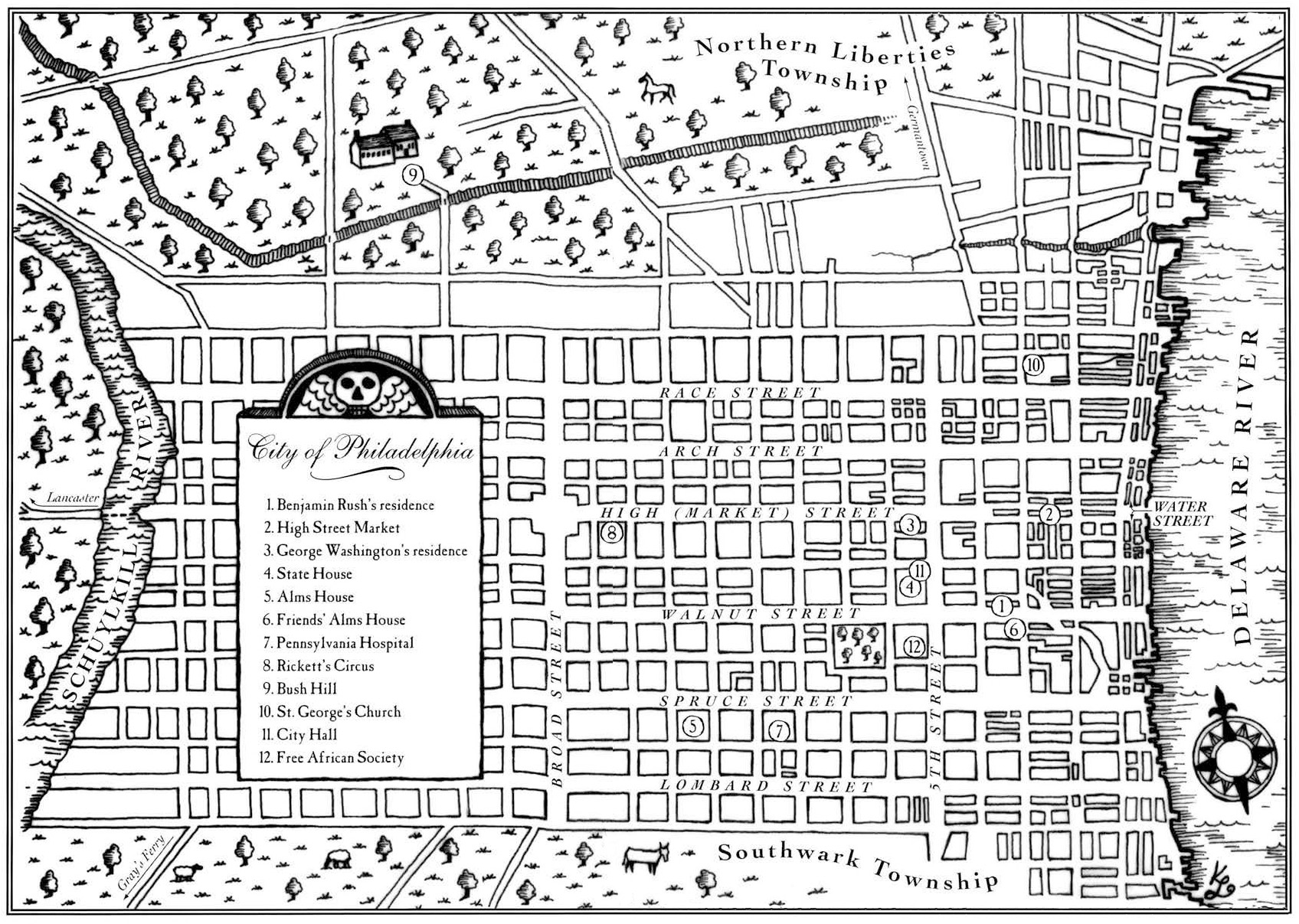

One and a half blocks from the market was the handsomely refurbished mansion of Robert Morris, a wealthy manufacturer who had used his fortune to help finance the Revolutionary War. Morris was lending this house to George and Martha Washington and had moved himself into another, larger one he owned just up the block. Washington was then president of the United States, and Philadelphia was the temporary capital of the young nation and the center of its federal government. Washington spent the day at home in a small, stuffy office seeing visitors, writing letters, and worrying. It was the French problem that was most on his mind these days.

Rich and poor do their food shopping along Market Street. (T HE L IBRARY C OMPANY OF P HILADELPHIA )

Not so many years before, the French monarch, Louis XVI, had sent money, ships, and soldiers to aid the struggling Continental Armys light against the British. The French aid had been a major reason why Washington was able to surround and force General Charles Cornwallis to surrender at Yorktown in 1781. This military victory eventually led to a British capitulation three years later and to freedom for the United Statesand lasting fame for Washington.

Then, in 1789, France erupted in its own revolution. The common people and a few nobles and churchmen soon gained complete power in France and beheaded Louis XVI in January 1793. Many of Frances neighbors worried that similar revolutions might spread to their countries and wanted the new French republic crushed. Soon after the king was put to death, revolutionary France was at war with Great Britain, Holland, Spain, and Austria.

Naturally, the French republic had turned to the United States for help, only to have President Washington hesitate. Washington knew that he and his country owed the French an eternal debt. He simply wasnt sure that the United States had the military strength to take on so many formidable foes.

Many citizens felt Washingtons Proclamation of Neutrality was a betrayal of the French people. His own secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson, certainly did, and he argued bitterly with Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton over the issue. Wasnt the French fight for individual freedom, Jefferson asked, exactly like Americas struggle against British oppression?

The situation was made worse in April by the arrival of the French republics new minister, Edmond Charles Gent. Gents first action in the United States was to hire American privateers, privately owned and manned ships, to attack and plunder British ships in the name of his government. He then traveled to Philadelphia to ask George Washington to support his efforts. Washington gave Gent what amounted to a diplomatic cold shoulder, meeting with him very briefly, but refusing to discuss the subject of United States support of the French. But a large number of United States citizens loved Gent and the French cause and rallied around him.

Next page