The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For ZXDN, who is my heart

The LORD shall watch over your going out and

your coming in,

from this time forth for evermore.

Psalm 121:8

Contents

Authors Note

This book is based on my work and research with New York Citys Department of Sanitation. Certain individuals portrayed in these pages preferred to remain anonymous, so I gave them pseudonyms, as indicated in footnotes. The chapter You Are a San Man combines some of my own experiences on the job with stories told to me by other Sanitation personnel. Portions of Garbage Faeries and On the Board appeared in the April 2011 issue of Anthropology Now .

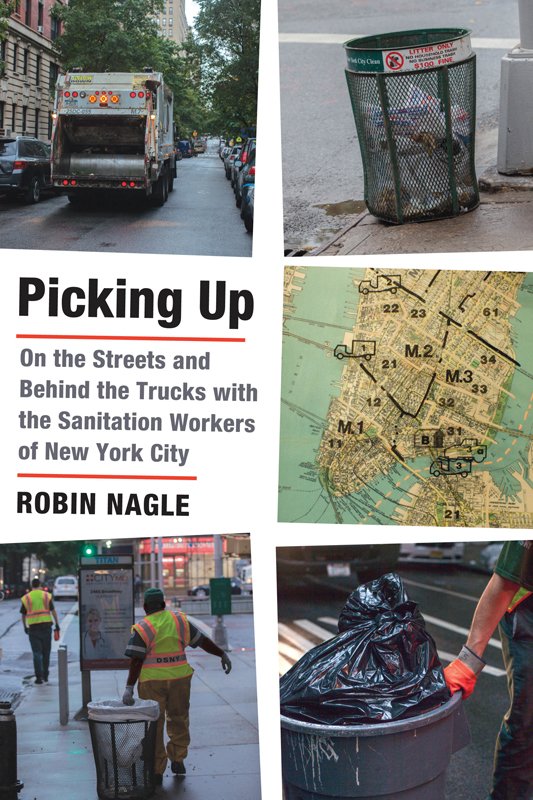

Prelude: Center of the Universe

I dont usually name my trucks, but this one I call Mona, after the sound she makes when I push her toward her top speed. She has other quirks typical of a collection vehicle with many miles on the odometer. Her shocks and seat springs stopped softening the jolts of the road long ago, and her side-view mirrors shimmy so hard that cars behind me look like jittery smears.

I am heading south during the evening rush hour on the Major Deegan Expressway in New York City, carrying a load of densely packed garbage to the dump (more properly called a transfer station). As I thread the trucks thirty-five-ton bulk through thick traffic, well aware that no one is glad to see me, the engines steady keening aligns with my own sense of caution. Though I own the roadfew motorists will play chicken with a garbage truckfifty miles an hour is plenty fast enough for me.

Just before the Major Deegan becomes the Bruckner, I descend from the highway to the gloomy streets of the South Bronx. Only recently has the neighborhood started recovering from decades of decay and neglect. I bump over a rutted road, cross a set of train tracks, and drive carefully onto a scale, where an unsmiling young man takes my paperwork. Diesel fumes and river water scent the air. Once the truck is weighed, I move toward the dump itself, a vast barnlike structure a few hundred yards farther on. Other trucks are already waiting, so I pull up to the end of the queue (never a line), set my parking brake, and ponder Monas noise again. Perhaps it isnt a keening. Maybe its a truck-ish manifestation of our journeys ritual gravitas, a mechanical form of circular breathing that lets her intone a single note without pause. She is the ten-wheel equivalent of a chanting monk.

* * *

This is a story that unfolds along the curbs, edges, and purposely forgotten quarters of a great metropolis. Some of the narrative is common to cities around the world, but this tale is particular to New York. It centers on the people who confront the problem that contemporary bureaucratic language calls municipal solid waste. Its a story Ive been discovering over the past several years, and from many perspectives.

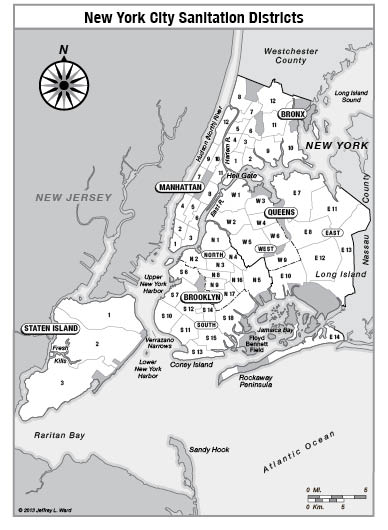

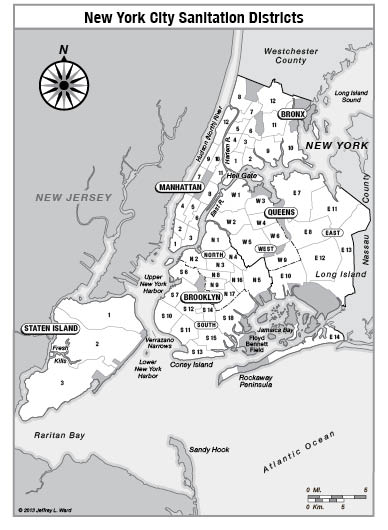

The job of collecting Gothams municipal waste and sweeping its streets falls mainly to the small army of men and women who make sure the city stays alive by wrestling with the challenge of garbage every day, fully aware that their efforts will receive scant notice and even less praise. This army makes up New Yorks Department of Sanitation, the largely unknown, often unloved, and absolutely essential organization charged with creating and maintaining a system of flows so fundamental to the citys well-being that its work is a form of breathing, albeit with an exchange of objects instead of air molecules. Or maybe its work is tidal: ceaseless ebbs and floods created by an almost gravitational pull between global economic forces that relentlessly shape both physical geographies and political landscapes. Just as a cessation of breath kills the being that breathes, or the stilling of tides would wreck life on earth, stopping the rhythms of Sanitation would be deadly to New York.

In many ways, the story is difficult to tell because it has no natural beginning or endso lets start in the middle.

* * *

Garbage transfer stations are not on most tourist itineraries, nor are their neighbors charmed by their ambience. Its safe to say that dumps are largely despised, as is the continual parade of large, loud trucks that feeds them. The public loathes the loads these carriers move, their comings and goings that never stop, the potholes they gouge into surrounding streets, the fouling exhaust, the trailing smell of trash that sometimes reaches farther than the laws of physics suggest is possible. We hate that transfer stations have to exist at all, no matter how remote their locations.

Im thinking about how such structures came into being in the first placesurely we could figure out a better way to manage our discardswhen a horn behind me breaks my reverie. Dump workers have been letting vehicles onto the tipping floor a few at a time, and theres a gap between me and the rest of the queue; I pull forward.

Then its my turn. My gut gives a familiar flutter of excitement, and I take Mona across the threshold. Of course she chants. Though we understand this place to be odious, it is nothing less than the juicy, pulsing, stench-soaked center of the universe.

The smell hits first, grabbing the throat and punching the lungs. The cloying, sickly-sweet tang of household trash that wrinkles the nose when it wafts from the back of a collection truck is the merest suggestion of a whiff compared to the gale-force stink exuded by countless tons of garbage heaped across a transfer station floor. The bodys olfactory and peristaltic mechanisms spasm in protest. Breathing through the mouth is no help, and neither gulp nor gasp brings the salvation of fresh air; theres none to be had.

While the stench throttles nose and throat, deafening noise assaults the ears. Collection trucks are loud anyway, but their sound is considerably amplified when several gather inside a huge metal shed and they disgorge their loads all at once. Piercing backup beeps and roaring hydraulics are accompanied by shrieks of metal against metal, and the acoustic onslaught reverberates off the walls like a physical force, so intense that it takes on a kind of aural purity. Workers who spend their shifts inside the facility wear fat red headphones, but those of us only passing through must suffer the cacophony. The best way to communicate is with hand signals.

Then theres the remarkable interior landscape. The floor of the cavernous spaceit feels as big as a few football fieldsis three-quarters buried under garbage piled higher than our trucks. Mist meant to suppress dust falls from nozzles on the distant ceiling and blends with garbage steam rising from the heaps to create a sepia haze that obscures corners and far walls and makes the trash recede into yawning darkness. An oversized bulldozer lumbers across the mass as if sculpting it. The mounds quake beneath its weight like the shivering flanks of a living being, some golem given sentience by an unlikely spark that animated just the right combination of carbon, discards, and loss.

The reek, the howling, the glooma newcomer would be forgiven for thinking hes stumbled into a modern-day staging of the Inferno . In the Third Circle of Hell, where the gluttonous are doomed to spend eternity wallowing in filth, even a poet as gifted as Dante couldnt make it worse than this. The Fourth Circle, in which the avaricious must bear great weights that they use to assault one another in perpetuity for the sins of hoarding and of squandering, is also perfectly represented. Trucks and bulldozers stand in for human beings, but the task of moving enormous burdens is similarly endless.