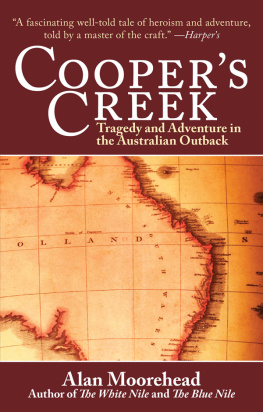

High adventureextraordinary

WASHINGTON STAR

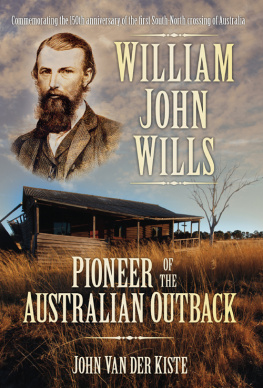

The story of one of the worlds strangest adventures in the worlds strangest land, the story of the expedition that preceded the opening of the interior of Australia drama, tragedy, emotion

BOSTON GLOBE

A fascinatied well-told tale of heroism and adventure, told by a master of the craft

HARPERS

A monument to a few tough men who crossed the continent because no one had done it beforechilling a tale of men against the elements

ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH

Few writers can so skillfully cast a spell over the readeronly when the whole vivid picture unfolds does one realize with what mastery it has been producedmoves as swiftly as a well-plotted suspense novel

CHICAGO NEWS

About the author:

ALAN MOOREHEAD,

an Australian himself, is the author of

Gallipoli, The Russian Revolution

and three books about Africa

No Room in the Ark, The White

Nile and The Blue Nile. He was

a foreign correspondent for

the London Daily Express during

World War II and has also written

several books about the war.

Published by

DELL PUBLISHING CO., INC.

750 Third Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10017

Copyright 1963 by Alan Moorehead

Dell TM 681510, Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

Reprinted by arrangement with

Harper and Row, New York, N.Y.

First Dell printingJanuary, 1965

Printed in U.S.A.

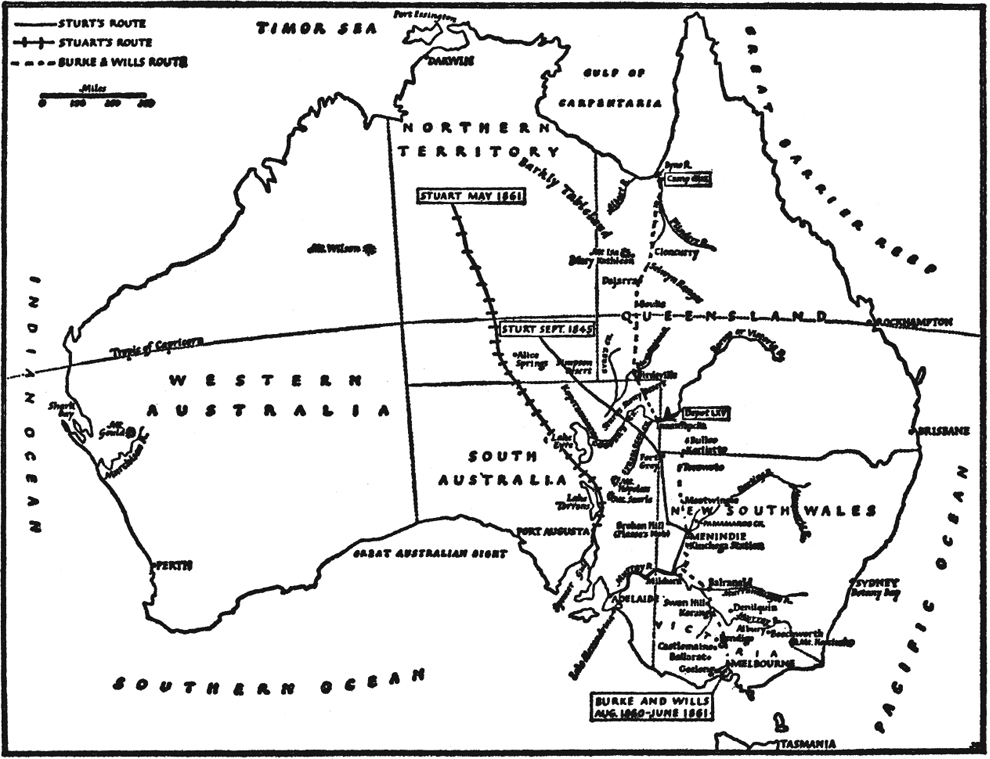

Contents

MAPS

(drawn by Miss Joan Emerson)

1

THE GHASTLY BLANK

HERE PERHAPS, MORE THAN ANYWHERE, HUMANITY HAD had a chance to make a fresh start. The land was absolutely untouched and unknown, and except for the blacks, the most retarded people on earth, there was no sign of any previous civilization whatever: not a scrap of pottery, not a Chinese coin, not even the vestige of a Portuguese fort. Nothing in this strange country seemed to bear the slightest resemblance to the outside world: it was so primitive, so lacking in greenness, so silent, so old. It was not a measurable man-made antiquity, but an appearance of exhaustion and weariness in the land itself. The very leaves of the trees hung down dejectedly, and they were not so much evergreen as ever-grey, never entirely renewing themselves in the spring, never altogether falling in winter. It was the bark that fell; it dried up and cracked on the tree trunks and then peeled off like the discarded skin of a snake.

Everything was the wrong way about. Midwinter fell in July, and in January summer was at its height; in the bush there were giant birds that never flew, and queer, antediluvian animals that hopped instead of walked or sat munching mutely in the trees. Even the constellations in the sky were upside down and seemed to belong to another system of the sun. As for the naked aborigines, they were caught in a timeless apathy in which nothing ever changed or progressed; they built no villages, they planted no crops, and except for a few flea-bitten dogs possessed no domestic animals of any kind. They hunted, they slept, just occasionally they decked themselves out for a tribal ceremony, but all the rest was a listless dreaming.

A kind of trance was in the air, a sense of awakening infinitely delayed. In the midsummer heat the land scarcely breathed, but the alien white man, walking through the grey and silent trees, would have the feeling that someone or something was waiting and listening. The smaller birds did not fly away as they did in Europe. The kookaburra approached, uttered its raucous guffaw, then cocked its head, waiting for a response. The kangaroo stood poised and watching. The earth itself had this same air of expectancy, as though it were willing the rain to fall, as though it were waiting for fertilization so that it could come to life again.

And in fact an awakening did occur in the south-eastern corner of the continent when the first white settlers arrived in 1788. Somehow European crops were made to grow in land that had never been tilled before, and imported cattle, horses and sheep managed to survive in a country where the farmer had no precedents to guide him. Every man was a Robinson Crusoe. A flood could and did wipe out a years labour in a single day, and when a drought began there was no knowing when it would ever end. Everything was new and had to be begun from the beginning.

But it was a healthy country. Along the coast at least there was a sparkle in the air, a sense of vigour, of light and space, that the colonists had never known in Europe. On the whole it was a mild climate by the seathey had about as much rain as England and the sun had no more than a Mediterranean warmthand by 1860 places like Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide were flourishing settlements.

Melbourne, the capital of Victoria, was by some way the most important of these places; and this had happened with bewildering suddenness. Barely ten years earlier Victoria had been a remote pastoral backwater, an appendage of the older settlement of New South Wales, a place only known vaguely as the Port Phillip district. Most of the little colonys affairs were managed from Sydney. No made roads or railways led off to the other Australian colonies, no telegraph existed, and twelve thousand miles of empty ocean divided the settlers from Europe. Apart from Melbourne and Geelong there was not another town worth the name, and it is doubtful if the population of the whole region, which was about the size of England, exceeded 80,000.

But then in 1850 Queen Victoria had agreed that a new colony should be created south of the Murray River and that it should bear her name; and in the following year gold was found near Ballarat. Gold could create a mass frenzy anywhereit had just done so in Californiabut in this little frontier community where the struggle for existence had been so hard people lost their wits. Bank clerks and civil servants left their jobs overnight to go off to the diggings, and not even the offer of double wages could hold them back. Ships putting into Port Melbourne were abandoned by their crews, and in the town itself women were left to carry on the shops and businesses. Cottages, La Trobe, the Lieutenant-Governor, wrote, are deserted, houses to let, business is at a standstill, and even schools are closed. In some suburbs not a man is left Prices shot up to impossible heights; an immigrant was obliged to pay 2 or more to get his luggage ashore, and as much again for a corner of a hotel room to sleep in.

And the gold was actually there, at first near Ballarat, then in Castlemaine and Bendigo and in a dozen other new strikes along the inland rivers. Prospectors with nothing but a pick and shovel, a bag of flour and a little tea, spread out through the north-east, penetrating into hills and valleys that had never been explored, and it was enough for the word to go out that someone had struck it lucky on the Ovens River for a new rush to begin. The gold, quite often, was lying there on the surface of the ground waiting to be picked up; they found nuggets in the roots of trees, in upturned grass, in the sands of shallow rivers. The Welcome Stranger nugget, weighing 2,284 ounces and worth 9,534, was covered by only two inches of soil.

By 1853 a thousand ships were arriving in Melbourne every year, and money had begun to lose all value in a welter of speculation. Land in the city went for 200 a footfive times the cost of land in Londonand men made money only to spend it again as quickly as possible. After months of grinding work at the diggings it was a wonderful thing for a man to light his cigar with a 5 note, to play skittles with bottles of French wine, or even in some cases to shoe his horse with golden horseshoes.

Next page

![Moorehead - Coopers Creek to LangTang II. [With plates, including portraits.]](/uploads/posts/book/221288/thumbs/moorehead-coopers-creek-to-langtang-ii-with.jpg)