Table of Contents

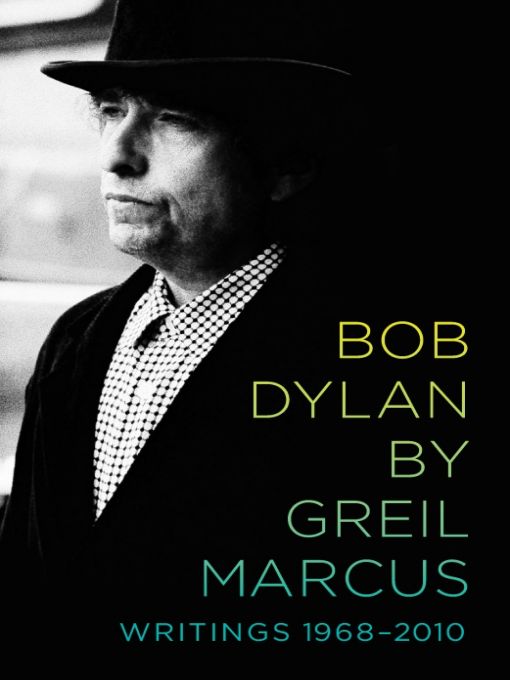

ALSO BY GREIL MARCUS

Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock n Roll Music

(1975, 2008)

Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century (1989, 2009)

Dead Elvis: A Chronicle of a Cultural Obsession (1991)

In the Fascist Bathroom: Punk in Pop Music, 1977-92

(1993, originally published as Ranters & Crowd Pleasers)

The Dustbin of History (1995)

The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylans Basement Tapes (2000, 2011, originally published as Invisible Republic, 1997)

Double Trouble: Bill Clinton and Elvis Presley

in a Land of No Alternatives (2000)

The Manchurian Candidate (2002)

Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads (2005)

The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice (2006)

When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening to Van Morrison (2010)

As Editor

Stranded (1979, 2007)

Psychotic Reactions & Carburetor Dung, by Lester Bangs (1987)

The Rose & the Briar: Death, Love and Liberty in the

American Ballad (2004, with Sean Wilentz)

A New Literary History of America (2009, with Werner Sollors)

FOR JENNY

WHERE I CAME IN

In the summer of 1963, in a field in New Jersey, Id gone to see Joan Baez, a familiar face in my hometown, in Menlo Park, California, and suddenly a familiar face everywhere elseshed been on the cover of Time. This day she was appearing at one of those old theaters-in-a-round, set up under a tent. She sang, and after a bit she said, I want to introduce a friend of mine, and out came a scruffy-looking guy with a guitar. He looked dusty. His shoulders were hunched and he seemed slightly embarrassed. He sang a couple of songs by himself, then he sang one or two with Joan Baez, and then he left.

I barely noticed the end of the show. I was transfixed. I was confused. This person had come onto someone elses stage, and while in some ways he seemed as ordinary as anyone in the audience, something in his demeanor dared you to pin him down, to sum him up and write him off, and you couldnt do it. From the way he sounded and the way he moved, you couldnt tell where he was from, where hed been, or where he was goingthough the way he moved and sang somehow made you want to know all of those things. My name it is nothing, my age it means less, he sang that day, beginning his song With God on Our Side, which would turn up the next year as the lynchpin of The Times They Are A-Changinand while the whole book of American history seemed to open up in that song, the countrys story telling itself in a new way, the song also kept the singers promise. As he sang, you couldnt tell his age. He might have been seventeen, he might have been twenty-sevenand to an eighteen-year-old like me, that was someone old enough.

When the show was over, I saw this person, whose name I hadnt caught, crouching behind the tentthere was no backstage, no guards, no protocoland so I went up to him. He was trying to light a cigarette, it was windy, his hands were shaking; he wasnt paying attention to anything but the match. I was just dumbfounded enough to open my mouth. You were terrific, I said, never at a loss for something original to say. He didnt look up. I was shit, he said. I was just shit. I didnt know what to say to that, so I walked off. I asked someone in the crowd who the person was who along with Joan Baez was getting into her black Jaguar XK-E, then the most glamorous car on the road. When I got back to California I went straight to a record store and bought The Freewheelin Bob Dylan, his second album, the only one in the shop. I couldnt figure out why some of the songsabout the John Birch Society and a ramblin gamblin Willie, something with a band I called Make a Solid Roaddidnt fit the songs described in the liner notes. I took it back and told the store owner there was something wrong with it. Oh, theyre all like that, he said. Ive had a lot of complaints. Come back next week and Ill have some good copies. But I never did go back. I fell in love with Dont Think Twice. I played it all day long. I figured if I exchanged my album it might not be on the next one.

For me, for a lot of other people, perhaps in ways for Bob Dylan himself, his life and work opened up from right about that time. Very quicklywith, say, Blowin in the Wind, Masters of War, A Hard Rains A-Gonna Fall, The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, a score more songs about conflict and justice, truth and lie, that could be epic and commonplace in the same moment, songs orchestrated by nothing more than the singers own bare guitar and harmonicaand then with the mid-sixties albums Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde, filled with visionary performances, most with equally visionary rock n roll not so much behind the songs as all through themBob Dylan became in the common imagination far more than a singer who had, by some happenstance, caught his moment. To do what hed done, Dylan wrote years later, you had to be someone who could see into things, the truth of thingsnot metaphorically, eitherbut really see, like seeing into metal and making it melt, see it for what it was and reveal it for what it was with hard words and vicious insight. In the early 1950s, kids like Bob Dylan watched someone seeing into metal and making it melt every week on The Adventures of Superman; in the next decade, as Paul Nelson puts it later in these pages, Dylan evoked such an intense degree of personal participation from both his admirers and detractors that he could not be permitted so much as a random action. Hungry for a sign, the world used to follow him around, just waiting for him to drop a cigarette butt. When he did theyd sift through the remains, looking for significance. The scary part is theyd find itand it really would be significant.

This is where I came in, as a writersix years after the show in New Jersey, at the end of Dylans adventure as an oracle on the run, just after he released his spare, cryptic album John Wesley Harding, an album of parables of the republic, riddles about its cops and robbers, and love songs that took the sting away.

Bobby Darin had three hit records under his belt when he announced his goal in life: I want to be a legend by the time Im twenty-five. He didnt make it, but Bob Dylan did.

Those are the first lines from a piece I wrote in 1969 that is not included in this collection of most of what, outside of two earlier booksone on Like a Rolling Stone, one on the songs that travel under the name of the basement tapesIve written about Bob Dylan over the years. In 1969 Bob Dylan was twenty-eight. Hed been a legenda story people passed on as if it might even be trueat least since 1964. But time moved fast thenBobby Darin, you can imagine, wanted to be a legend by the time he was twenty-five because after that it might be too late.

As a chronicle of events happening as they were written aboutwhich this book, much of it a matter of reviews, reports, sightings, comment in monthly or bi-weekly magazines and weekly newspapers, to some degree isthat heroic period hangs over what I wrote. Its a given that I am writing about someone who has done signal work, has made music so rich that even as it appeared it suggested it might be untouchable, not merely by others but by Dylan himself. It was an enormous achievement: the rewriting, in all senses, of American vernacular music, from the fiddlers who took up Springfield Mountain at the end of the eighteenth century to Little Richard, at once a recapturing of the past and the opening of a door to what had never been heard and had never been said. All of that is in this book. But at least for its first half it is present as a shadow, a shadow cast by a performer who, as I began to write about him, had fallen under it himself.