For Samantha and Josie

FOREWORD

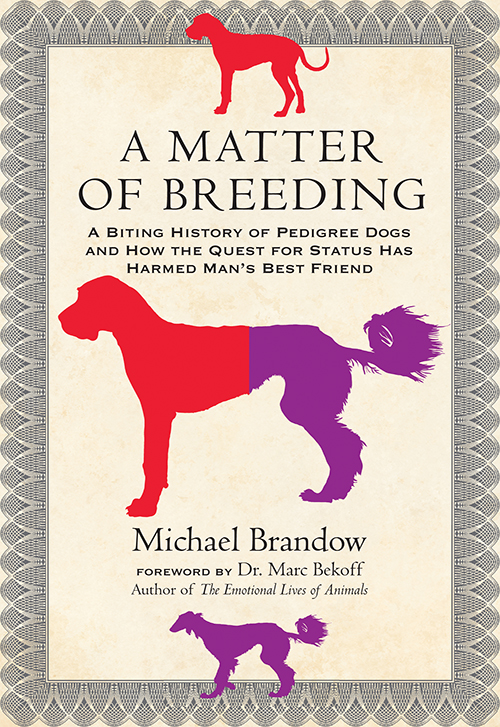

For many years Ive researched human-animal interactions, writing several books, including The Emotional Lives of Animals and, with Jane Goodall, The Ten Trusts, and cofounding the organization Ethologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. I am profoundly committed to the notion that we are our companions trusted guardians, not their owners. Additionally, I feel strongly that dogs (and other animals) are not commodities and that causing intentional pain to them is unethical, inhumane, and unnecessary.

From this standpoint, I believe its timeindeed, its long overdueto have reasoned discussions and debates about dog breeding. Many major studies document a rising number of breed-specific health problems and suggest were in the midst of an alarming health crisis. A two-month-old bulldog should not need routine eye surgery nor should a four-year-old Labrador show signs of hip dysplasia. Clearly theres something wrong in the world of pedigree dogs. Ive argued that we dont need any more purebred dogs, and as Michael Brandow asks in this most important book, Why do we go on hurting the ones we love?

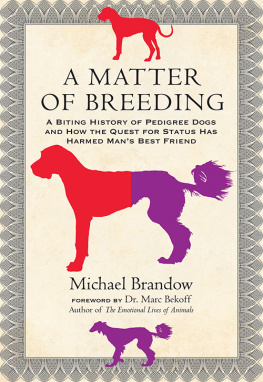

With a background in journalism, dog care, and community activism, Michael Brandow is a close observer of canine culture. His eye-opening book, A Matter of Breeding, is what I regard as an ethically urgent and essential read. Brandow addresses head on the issues of snobbery and consumerism inherent to purebreds, with remarks on designer dogs, the second-largest but fastest-growing segment of the dog industry. Rich in history, the book traces the commercial origins of the Boston terrier, English bulldog, and other types that were marketed as highfalutin status symbols beginning in the nineteenth century.

Upper classes, the author reminds us, have long set the benchmark for valuing dogs according to the social status they confer. From ancient court dogs and royaltys highly formalized hunting rites to the creation of kennel clubs by Gilded Age elites and the strict but often arbitrary standards used in competitions to judge on style, not substance, Brandow demonstrates that a major motivation for owning identifiable types has been their aristocratic appeal. And, while we satisfy our self-centered desires, millions upon millions of dogs unnecessarily suffer and die way before their time.

While the modern cult of pedigree and the very concept of officially recognized breeds are inventions of Victorian England, these ideas have taken root in our culture with profound consequences for dogs and people alike. Then, as now, much of the impetus for having fancy pets has revolved around what theyre supposed to say about the owners position, spending power, connoisseurship, and tastein other words, how they reflect upon their owners breeding. In showing how far we humans have gone in refashioning dogs to freakish extremes that go against common sense, even exaggerating their behaviors in ways to denote rarity and lavish expenditure, the author urges us to think critically about our breed prejudices and ask ourselves whether preserving them is worth all the damage done to dogs in the process. By examining a persons preference for a purebred to a nonbreed, we can see how these consumer choices are anything but neutral. We must also ask ourselves how weas dog loverscan justify bringing more animals into this world when millions are already dumped in shelters, often because theyve failed to live up to expectations that are unrealistic and, according to Brandow, somewhat hypocritical.

Brandows provocative analysis makes it clear that our everyday assumptions about dogs have implications for the social biases we have against each other, sources of much injustice. As he points out, if were going to impose human beliefs on other animals, we could at least use those we claim to have. This contradiction, he suggests, could explain why so little effort has been made to purge dog breeding of misplaced priorities and pseudoscience of the past. In fact, those entrusted with the welfare and improvement of mans best friendkennel clubs and the scientists they fund, breed clubs, puppy mills, and reputable breeders alike, and local veterinarians who clean up the mess without commentconstitute a colossal dog industry that all too often privileges a recognized brand with class connotations (papillon, golden, Portuguese) over an individual animals health. As Ive said before, we shouldnt breed for qualities that appeal to humans but do little for the dogs. Theres nothing noble about encouraging anatomical, physiological, or genetic maladies that guarantee compromised lives, pain, suffering, and early deaths. When I hear a dog with a squashed face pant as if he or she is going to pass out it sickens me. The best way to stop the breeding of purebreds is to stop buying them.

Brandows unflinching social history, viewed with humor and sarcasm, remains a very serious, significant, and timely message and is a very important first step toward reforming our cultural prejudices against mongrels due to their uncertain origins and substandard appearance. He unmasks the sordid past of dog shows, the impromptu creation of the oddities weve come to accept as normal, and the alarming conservatism of some experts who still insist, against all evidence to the contrary, that purebred dogs are likely to be healthier, smarter, or more loyal and trainable than common mutts. My hope is that after reading A Matter of Breeding, people eager to adopt a canine companion will first look to their local shelters and not a breed directory. Adopting a dog in need is the compassionate and, it turns out, often the more rational consumer choice. Its a win-win situation for the dogs and the people. What could be better? Breedingmeaning both the disturbing legacy of bias and inequality celebrated each year at the Westminster Kennel Club dog show, and the ongoing production of surplus pets while millions await rescue or deathneeds to be reconsidered in a major way. This landmark book will surely motivate people to begin to ask the hard questions and to answer them, so that dogs benefit from these discussions. Im sure the dogs who are chosen will be forever thankful for people who make this decision. Its a malicious double-cross to betray their deep feelings of trust in our having their best interests in mind.

Once again, to quote the author, Breeding for blood purity and formal perfection is pure madness and always has been. Amen.

Dr. Marc Bekoff

INTRODUCTION

I found my inspiration for this impolite volume while trying to dodge something else. Wandering the sidewalks of Manhattan in the midst of an unsavory study on poop-scoop laws with my newfound mutt from a local shelter, I started wondering: what was so appealing about purebred dogs? I know many of us grew up with them. These were, after all, what good middle-class families had in those days, and preferably the latest model. But what gave birth to the widespread belief that being seen with a fancy breed makes you fancier than someone with a good old-fashioned mutt?

Pounding the pavement as a dog walker for ten years, I had as wide a catalog selection as my powers of observation could handle, a continual pooch panorama with all the standard shapes, sizes, and colors competing for attention. In a sense, I didnt need this rainbow coalition to tell me anything new. Having spent my life with breeds and nonbreeds alike, sat for hundreds in the homes of New Yorks elite, apprenticed with a dog trainer, performed with my own on national television, and passed thousands of hours volunteering at a dog park chatting with every imaginable breed of owner, Id learned to love all dogs