Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Far too many people to list here proved invaluable in the production of this book. A few deserve special recognition.

George Witte spotted the potential of the project, and Michael Homler lent it wisdom, a keen eye, and a firm pen.

Rob Spillman, Heidi Julavits, and Peter Manseau offered excellent advice on excerpts that appeared in Tin House, The Believer, and Search, respectively.

Im quite lucky to have an agent, Devin McIntyre, willing to put out one fire for each fire I start. He has also taught me a thing or two about writing, which is as high a compliment as I know how to pay.

Last, this book would not have happened at all without Lynn Laufenberg.

Im indebted to each of you, and to many more besides. If Utopia ever arrives, Ill invite you all to my home there.

A JOKE

Only in us does this light still burn, and we are beginning a fantastic journey toward it, a journey toward the interpretation of our waking dream, toward the implementation of the central concept of utopia. To find it, to find the right thing, for which it is worthy to live, to be organized, and to have time: that is why we go, why we cut new, metaphysically constitutive paths, summon what is not, build into the blue, and build ourselves into the blue, and there seek the true, the real, where the merely factual disappears incipit vita nova.

ERNST BLOCH, The Spirit of Utopia

Utopia is in a bad way.

Utopian thought can be broadly defined as any exuberant plan or philosophy intended to perfect life lived collectively.

As Ernst Bloch suggested, the historical drive toward utopia is best understood as a kind of light, or fire. Utopian thought sparked in antiquity with descriptions of fancifully perfect countries in Plato and Aristotle, smoldered like a coal mine fire through the Middle Ages with early monasticism and portraits of Eden and Heaven, burst into eponymous conflagration with Sir Thomas Mores Utopia in 1516, caught and spread across Europe with religious fervor for 150 years, tacked for a century and turned secular, flared anew with the American Revolution and the French Revolution, burned like wildfire through the nineteenth century, and forged at last the ideologies that squared off in the twentieth century for what Thomas Mann called a worldwide festival of death, this ugly rutting fever that enflames the rainy evening sky all round. Utopian thought bears its share of responsibility for that scorching of the face of the earth. As a word, it had already acquired a pejorative connotation, but after World War II utopia was no longer just a synonym for navet. It was dangerous. Now, decades further on, in a new century and a new millennium, earnest utopian thought and earnest utopians are a glowing ember at best, and utopias legion failures seem to suggest that the best course of action would be to crush itto snuff it for good.

By any rational measure, I should suggest this myself. But I wont.

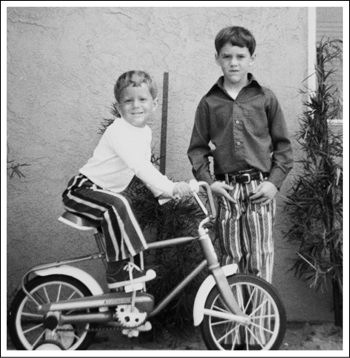

This is a photo of my brother, Peter, and me in the backyard of our home in a master-planned southern California community in 1972. For six years we lived on a street called Utopia Road.

Im there on the left, looking a bit too proud of those pants. The hopefulness of Utopia Road is apparent in the staked landscaping, but the dirt on the ground reveals the place isnt even finished yet. I like it that the bikes wheels sit right on the edge of the photograph. Im perched on the rim of the pictures contained little world.

As a rule, utopias slip. They slip in the transition from conception to implementation; they slip as a result of financial expedience or frail psychology. Utopia Road had slipped from the ambitions of the likes of Frederick Law Olmsted and Ebenezer Howards Garden City movement. By the time it filtered down to us the promise of a better life through better suburbs was hogwash. Considering for a moment only its internal effects, the vast shelter of Utopia Road, its informal biosphere, left its children safe but stunted, pure but uncertain. We were innocent, but in for a fall. Utopia Road housed us, but did not raise us.

There are a number of dichotomies in the image of my brother and me. The contrasts of our hair and our shirts, for example. I dont want to foist an agenda on a simple effort at documentation (the angle of the shot suggests the photographer was my sister, Amy, age ten), but various features of the pictures subjects do appear to offer commentary on their context. Peters erect stance and his hands lodged firm in his pockets suggest the certitude and resolve of a homesteader, whereas my looser pose and my foot ready to crank down on the bikes pedal fairly screams out for abandoning a utopia already turned dystopian. The fashions of the imagethe fifties fins on my Schwin, our sixties hair and seventies clothesstraddle a cultural revolution characterized by a rekindled, albeit narrowly focused, utopian spirit (i.e., free-love communes). Finally, my brothers annoyed squint and my goofy grin offer contrasting critiques: Peter intends to stick it through the hard times to make utopia work, while Im ready to zip out of the frame even with training wheels and an untied shoe.

Like the picture, the history of utopian thought and literature refracts a broad range of dichotomies: rich versus poor, rural versus urban, past versus future, war versus peace, wilderness versus civilization, high-tech versus low-tech. Even the name is half a duality. In the preface to Utopia , More explained that utopia, Greek for no place, would become eutopia, or good place, whenever some earnest visionary proved able to realize its dream.

There was no earnest visionary responsible for Utopia Road. It wasnt ever meant as a good place; it was a scheme to make a buck. The name Utopia Road was some real estate developers idea of a joke.

The idea of a joke is central to the history of utopiaor at least to my version of it.

More borrowed from a broad range of classical and contemporary sources in the creation of Utopia , striking them together as flint stones to ignite the utopian blaze. But just how seriously he meant the exercise to be taken has long been a matter of conjecture. The influence of Utopia is undeniable. No quixotic adventure, no bureaucratic catch-22, no charming Casanova, nor even any odyssey home is as universally recognized as the name of the perfect world we forever chase, the bittersweet flavor of hope. Among words that have leaped from fiction to reality, advanced from noun to adjective, it stands alone. But what did More mean by it? Theories characterize the age in which they are professed better than they characterize More or the book. Yet its not going out on a limb to suggest that the history of the world since 1516 is a protracted history of not getting the joke of Utopia.

An inability to tell whether he was just kidding describes Thomas Mores personal life as readily as it describes his book. Famous for his wit, Mores friends were quick to note that a taciturn air made perceiving his humor no simple task. He apparently enjoyed this. Mores arid nature is palpable today. Does the poker-faced expression of Hans Holbeins famous portrait of More disguise a nut flush or a lowly pair? Does More have you beat, or is he bluffing?