* * * *

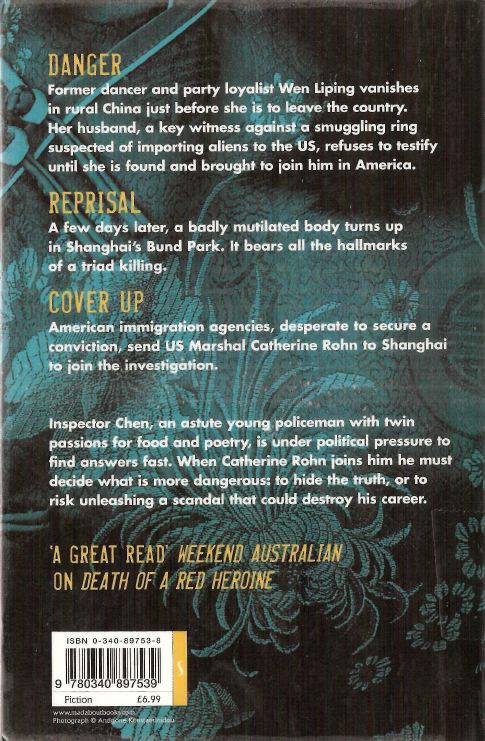

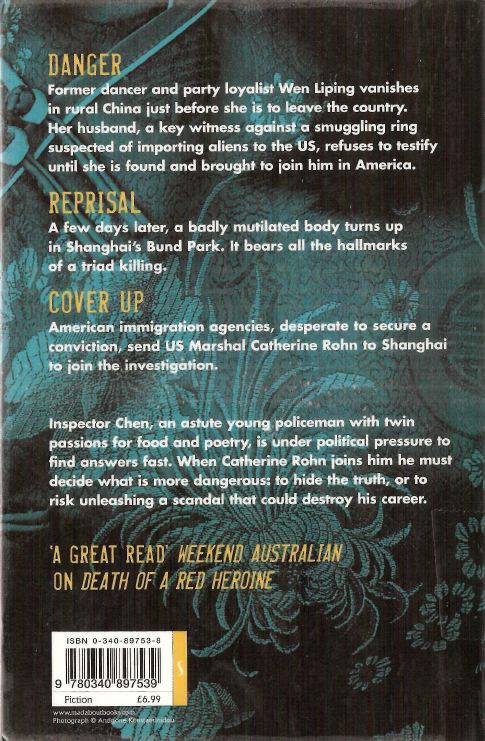

A Loyal Character Dancer

[Chief Inspector Chen Cao 02]

By Qiu Xiaolong

Scanned & Proofed By MadMaxAU

* * * *

Chapter 1

hief Inspector Chen Cao, of the Shanghai Police Bureau, found himself once again walking through the morning mist toward Bund Park.

In spite of its relatively small size, about fifteen acres, the location of the park made it one of the most popular places in Shanghai. At the Bunds northern end, the front gate of the park faced the Peace Hotel across the street, and its back gate connected with the Waibaidu Bridge, a name that remained unchanged since its completion in the colonial era, meaning literally Foreign White Crossing Bridge. The park was especially celebrated for its promenade of multicolored flagstones, a long curved walkway raised above the shimmering expanse of water which joined the Huangpu and Suzhou rivers. From its height, people could look out to view vessels coming and going against the distant Wusongkou, the East China Sea.

The front gatekeeper, a gray-haired, red-armbanded woman surnamed Zhu, yawned and nodded to Chen on that April morning as he tossed a green plastic token into the token box. Several of the people who worked there knew him well.

That morning, Chen was one of the earliest birds to arrive in the park. He walked to a clearing in the central area that was surrounded by poplar and willow trees. The white European-style pavilion with its spacious verandah stood out in pleasant relief against the newly painted green benches. The dewdrops clinging to the foliage glistened in the dawn light like a myriad of clear eyes.

The appeal of the park was enhanced for Chen by its associations. In his elementary-school years, he had read about the parks history. The official textbook of the time said that at the turn of the century the park had been open only to Western expatriates. There had been signs on the gates saying: No Chinese or dogs allowed, and red-turbaned Sikh guards stood there to bar the way. After 1949, the Communist government considered this a good example of Western powers attitudes in pre-Communist China, and it was often cited in patriotism education. Had this actually happened? It was hard to establish the truth now, as the line between truth and fiction was always being constructed and deconstructed by those in power.

He mounted a flight of steps to the promenade, breathing in the fresh air of the waterfront. Petrels glided over the waves, their wings flashing in the gray light, as if flying out of a half-forgotten dream. The dividing line between the Huangpu River and Suzhou River became visible.

The park appealed to Chief Inspector Chen, however, for a more personal reason than its beauty or history.

In the early seventies, as a waiting-for-assignment high-school graduate, out of school, out of a job, he had come to practice tai chi in the park. Two or three months later, one mist-enveloped morning, after yet another halfhearted attempt at copying the ancient poses, he came upon a worn-out English textbook on a bench. How the book came to have been left there, he failed to discover. People sometimes placed old newspapers or magazines on the seats as protection from the dampness, but never a textbook. He carried the book to the park for several weeks, hoping someone might claim it. No one did. Then one morning, frustrated with an extremely difficult tai chi pose, he opened the book at random. From then on, he studied English instead of tai chi in the park.

His mother had worried about that change. It was not considered in good political taste to read any book except Quotations from Chairman Mao. However, his father, a neo-Confucian scholar, predicted that studying in the park might be propitious for him, in accordance with the ancient theory of wuxing: Among the five elements in Chen, water was lacking a little, so any place in association with water would benefit him. Years later, when he tried to look up that particular theory, Chen could not find it. Perhaps it had been made up for his benefit.

Those mornings in the park sustained him through the years of the Cultural Revolution. And in 1977, he entered Beijing Foreign Language University, having obtained a top English score on the newly restored college entrance examination. Four years later he was assigned, through another combination of circumstances, to a job at the Shanghai Police Bureau.

In retrospect, Chens life seemed to be full of the ironic causalities of misplaced yin and yang, like that misplaced book in the park, or his misplaced youth of those years. One thing led to another, and to still another, so the result could hardly be recognized. The chain of causality was perhaps more intricate than Western mystery writers, whose works he translated in his spare time, would care to admit.

On the cool April breeze, a melody wafted over from the big clock atop the Shanghai Customs Building. Six thirty. It had played another tune during the Cultural Revolution: The East Is Red. Time flowed away like water.

In the early nineties, under Deng Xiaopings economic reform, Shanghai had been changing dramatically. Across Zhongshan Road, a long vista of magnificent buildings, which had once housed the most prestigious Western companies in the early part of the century and then Communist Party institutions after 1950, were now welcoming back those Western companies in an effort to reclaim the Bunds status as Chinas Wall Street. Bund Park, too, had been changing, though he did not like some of the changes. For example, the postmodern concrete River Pavilion stood like a monster beside him, slouching against the first gray of the morning, watching. So, too, had Chen changed from a penniless student to a prominent chief inspector of police.

Still, it remained his park. In spite of a heavy work load, he managed to come here once or twice a week. It was close to the bureau, a fifteen-minute walk.

Not too far away, a middle-aged man practiced tai chi, striking a series of poses: grasping a birds tail, spreading a white cranes wings, parting a wild horses mane on both sides ... Chief Inspector Chen wondered what he might have become had he persisted in practicing. Perhaps he would now be like that tai chi devotee, wearing a white silk martial arts costume, loose-sleeved, red-silk-buttoned, with a peaceful expression on his face. Chen knew him. An accountant in an almost bankrupt state-run company, yet at that moment, a master moving in perfect harmony with the qi of the universe.

Chen took his customary seat, a green-painted bench which stood under a towering poplar tree. Carved on the back of the bench in small characters was a slogan that had been popular during the Cultural Revolution: Long Live the Proletarian Dictatorship. The bench had been repainted a couple of times, but the message showed through.

He took a collection of ci out of his briefcase and opened to a poem by Niu Xiji. The mist disappearing / against the spring mountains,/the stars few, small / in the pale skies, / the sinking moon illuminates her face,/the dawn in her glistening tears / at parting.... It was too sentimental for the morning. He skipped several lines to reach the last couplet: With the green skirt of yours in my mind, everywhere,/everywhere I step over the grass so lightly.

Another coincidence, he mused, tapping his fingers on the bench back. Not too long ago, in a riverfront cafe on the Bund, he had read this couplet for a friend, who now stepped over the green grass far, far away. Chief Inspector Chen had not come here, however, to indulge in nostalgia.

Next page