Cover copyright 2015 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The epigraph taken from Revolution in the Revolution in the Revolution is quoted by permission of Gary Snyder. The epigraph from The Night of the Iguana is drawn from the film of that name and does not appear in published versions of the play.

Portions of material appearing in chapters for March 14 and 15 were previously published in A Glimpse of the Wild, introduction to The Jungle at the Door: A Glimpse of Wild India by Joan Myers (photographer). George F. Thompson Publishing, 2012.

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are from the authors collection.

A Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest

The Walk

River of Traps: A New Mexico Mountain Life (with Alex Harris)

Salt Dreams: Land and Water in Low-Down California (with Joan Myers)

Enchantment and Exploitation: The Life and Hard Times of a New Mexico Mountain Range

Valles Caldera: A Vision for New Mexicos National Preserve (with Don J. Usner)

Seeing Things Whole: The Essential John Wesley Powell (editor)

For

Art Ortenberg

19262014

who set the standard for commitment

and

Mary Elizabeth Burford

19572011

rarest and bravest

The Unicorn is captured

And presented to the royal court in the hunters snare.

Creeping, it frees itself from the snare pole

And heals itself with vipers venom.

Engelberg Codex 314, fol. 150v152, ca. 1400

Shannon: On the side, Shannon has been collecting evidence.

Hannah: Evidence of what?

Shannon: Mans inhumanity to God.

Hannah: What do you mean by that?

Shannon: The pain we cause Him. Weve poisoned His atmosphere; weve slaughtered His wild creatures.

Tennessee Williams, The Night of the Iguana

From the masses to the masses the most

Revolutionary consciousness is to be found

Among the most ruthlessly exploited classes:

Animals, trees, water, air, grasses

Gary Snyder, Revolution in the Revolution in the Revolution

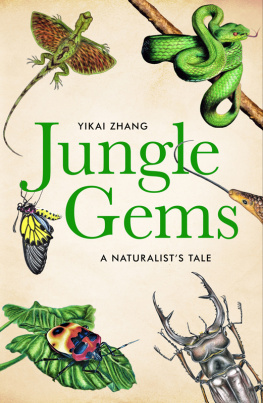

S trange paths lead to unexpected places, and sometimes the world opens up. Early in 2009 I researched efforts in central Borneo to protect a forest where captive orangutans were freed and reintroduced into the wild. Months later, I gave a brief talk on the project to a roomful of strangers in Washington, DC. One of those strangers, Jack Tordoff, telephoned the following week. He asked, How would you like to write about saola?

About what?

I had never heard the word saola spoken.

Tordoff explained that saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) were among the rarest large animals on Earth and that they became known to Western science only in 1992. He said they constituted the sole species of a unique genus of bovidsgrazing animals that include antelopes, goats, cattle, bison, and other ruminants. He added that they lived under constant threat, mainly from illegal snaring, in their limited range in the Annamite Mountains that divide Vietnam and Laos. He also said that they were beautiful, enigmatic, and, for him as well as many other conservation biologists, inspiring. Tordoff invited me to attend a meeting of the Saola Working Group, or SWG, a subunit of the Asian Wild Cattle Specialist Group of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, in Vientiane, Laos, in August of 2009.

The meetings energetic and dedicated coordinator was Bill Robichaud, a field biologist experienced in Southeast Asia, particularly Laos. Robichaud and I began a conversation that continued stateside. Eventually, in February and March of 2011, I was privileged to join Robichaud on a journey, recounted here, into remote corners of the NakaiNam Theun National Protected Area in Laos, hard by the international border with Vietnam. Our expedition had multiple purposes, principally involving reconnaissance of potential saola habitat and evaluation of poaching pressure. Our mission was also diplomatic in the sense that it was intended to build support for wildlife conservation among indigenous villagers living or hunting where saola might be found. Overall we hoped to advance priorities identified by Robichaud and his SWG colleagues and to contribute in some way, no matter how small, to the groups paramount goal, which wasand remainsto save the saola from extinction.

Joined by two Lao university students, and later by a staff member of the agency responsible for the protected area, we traveled by car from Vientiane to Nakai, a frontier town roughly hewn from the forest of central Laos, and thence by boat across the vast reservoir of the Nam Theun 2 Hydroelectric Project. We continued upriver into the Annamite Mountains, which are known as the Sayphou Louang in Laos and whose crest forms the international border with Vietnam. We hiked overland to the village of Ban Tong and procured new boats to take us up another river, the Nam Pheo, to the farthest village reachable by boat. There we lingered several days before hiring guides and porters to accompany us on a trek into the vast backcountry, beyond the frontiers of the village world. Our destination was the canyon-cut watershed of yet another river, the Nam Nyang, a land where we hoped to find evidence of living saola and upon which blue Western eyes like Robichauds and mine had never gazed.