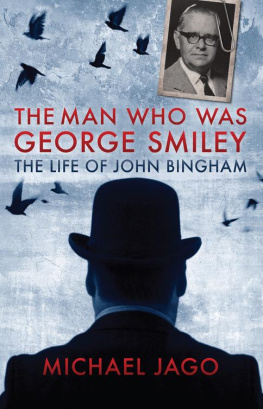

John Bingham - Five Roundabouts to Heaven

Here you can read online John Bingham - Five Roundabouts to Heaven full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Five Roundabouts to Heaven

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Five Roundabouts to Heaven: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Five Roundabouts to Heaven" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Five Roundabouts to Heaven — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Five Roundabouts to Heaven" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

John Bingham

Five Roundabouts to Heaven

Chapter 1

I had been looking forward all day to the visit. Indeed, I had been looking forward to it ever since we had planned our trip to the south of France, and I had arranged the route so that we would pass through Orleans. It was a visit that I had wanted to make for a long time, a kind of pilgrimage to a shrine of happiness now suitably veiled in the rosy mists of youth.

Nineteen years is a long time. One cannot remember everything, and the tendency on occasions such as this is to remember only the happiness. The weather seems always to have been warm and sunny, the days filled with love and laughter, the nights throbbing with the notes of the nightingales in the woods, and, in my case, with the blithe croaking of the amorous frogs in the moat around the chateau.

If I concentrate hard enough, I can, of course, recall that there were minor irritations and frictions, but it is true to say that they never lasted long. We were all too young, too filled with the joy of living; and perhaps the mild and gentle air of the wooded Sologne country was itself an antidote to prolonged bitterness.

Even the pangs of youthful jealousy have a curious sweetness in retrospect, for with the near approach of middle age the emotions, in matters of the heart, tend to be flattened, and the ecstasies and agonies toned down.

One has seen it all before, perhaps many times: this, one says, is where I came in. And if one decides to see the show again, one knows how the reel will run, amiably anticipating the pleasant periods, suitably fortified against the pains and pangs. Such is the penalty and such is the protection which the years bring you.

What makes for happiness depends upon ones age. We, who stayed at the chateau to learn French, were all young, of varied nationalities, and the road ahead seemed straight and sure, and to lead inevitably to a splendid fulfilment of such vague hopes for the future as we nurtured.

We had no doubts. We worked a little, we played tennis, gardened, and bathed in the lake in front of the ch,teau. In winter we went shooting. We fell in love, I need hardly add, some of us for the first time, and vowed undying faithfulness with all the confidence of extreme youth.

Our love was pure and idealistic, romantic and sweet. Looking back now, with a soul which is tarnished with dishonour and frayed round the edges, I am often amazed at this.

There was no hanky-panky at the chateau. And if I use a coarse music-hall expression in association with something which was fresh and beautiful, I ask you to be charitable, and to blame the span of the years and half a working lifetime which has been spent in different parts of the world. One is inclined to become crude.

I have said that I am often amazed at the unsullied nature of our feelings, and that is strictly true: often, but not always. For now and again, like the memory of the scent of a rose garden to some poor sufferer in a crowded town hospital, I catch a whiff of the fragrance of those earlier feelings, and I understand how we felt. A tune, such as My Blue Heaven, will naturally bring it back to me, or a particular type of perfume favoured by the young: but I may also catch it, suddenly and unexpectedly, walking along a street, or even in a crowded public house. It had always been, hitherto, a thin wraith of the real thing, but I felt that if I went back to the chateau, saw it standing there, with its light grey walls and blue shutters, at the end of the long drive of poplars, I would be able to recapture for a space not merely the full flavour of those past days, but also a glimpse of Philip Bartels as he then was.

I think I wanted to refresh my memory of the Bartels of those days almost as much as I wished to inflict upon myself the sweet pain of thinking of times now gone forever.

In spite of all that has happened, in spite of what Macdonald of Scotland Yard, and one or two others, have said, I still regard Bartels not only as my friend but as one of the most lovable characters I have ever known. Perhaps I, alone, understood what he felt.

All day, then, I had looked forward to this visit with a rising emotion, a physical disturbance of the stomach nerves, which amounted to veritable tension.

Two of the other three in our party knew nothing of the excitement within me; they thought of the excursion as only a casual visit to a familiar haunt. To them I must have seemed silent and broody that day. I was even asked, when I made a mere pretence of eating lunch, whether I felt quite fit.

Later that day I left them to stroll round Orleans, and took the car and drove through the little village of Verlin and out again to where the road was bordered by fields of corn, crisply brown and sprinkled with poppies and cornflowers.

The sun was at distant tree-top level when I pulled the car in to the side of the road, a few yards from the end of the poplar drive, and switched off the engine.

The evening was silent except for the creak of a cart on some distant farm and the faraway barking of a dog. The sky was cloudless. I climbed out of the car, and closed the door, and looked up and down the road. There was nobody in sight, and as I made my way towards the end of the avenue leading to the chateau, the sound of my shoes upon the hard road seemed uncannily loud.

For a second I experienced one of those curious sensations in the course of which you wonder whether you are really alive, and then the feeling was past. I walked slowly, now that the fulfilment of my ambition was at hand, wishing to savour every minute, every second.

It was at first my plan to walk down the avenue, but at the last moment I decided against it. The family no longer lived there, and I had heard from one of the brothers that it was now the home of two families of American Air Force officers who were stationed in Orleans. They had set up a kind of communal cocktail bar in the entrance hall. If they were now sitting drinking on the terrace, they would be in a position to watch me walking down the long avenue and to speculate upon what I wanted.

I had no doubt that I would be hospitably received if I explained the nature of my visit, even though I was a stranger, but I did not wish to spend my precious time talking to other people, be they American, English, or French. My rendezvous was with the happy ghosts of the early 1930s, not with the worried flesh and blood of postwar years.

I turned aside, therefore, into the woods which pressed close upon the poplar-lined drive, following a path which I knew well of old, which twisted and turned, but which eventually passed by the tennis courts, and by the side of the house, and led to the rising ground on the other side of the chateau.

It was a path which Bartels and I had often taken together, in the old days, when we wished to cross the Orleans-Blois highway to try for partridges on the land across the road. We preferred it to the avenue, for there was always the chance of a shot at a rabbit or a pigeon.

I trod it now, stepping as quietly as the leaves and twigs would permit, for the closer I came to the house the less I wished to be disturbed. Thus, stealthily, dreading equally the querying word or friendly shout, I returned like a poacher to the scene of my happiness.

I passed the great rabbit burrow, where we had once lost a ferret, and caught a glimpse, as I neared the house, of the cottage where grizzled old Georges Durois, the garde de chasse, used to live with his wife, Marie. Both are long since dead. (How he would grumble when I missed the rabbits which his ferret put out for my inexpert marksmanship!)

Then, close by the house, to the left of the path, I saw a weather-beaten wooden hut and paused, for I did not recall it, though to judge by its appearance it had been there many years. It stood among some young trees, surrounded by brambles and other bushes, and appeared to serve no useful purpose.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Five Roundabouts to Heaven»

Look at similar books to Five Roundabouts to Heaven. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Five Roundabouts to Heaven and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.