The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Mum and Dad

Americans are inclined to look everywhere but under their noses for art.

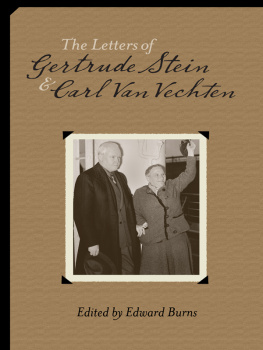

Carl Van Vechten

Contents

Prologue

Concealed within rural Connecticuts verdant undergrowth, two young menone white, the other blackstripped naked in the heat of a July afternoon in 1940. They had done this before; they knew the routine. Standing face-to-face, each reached out to place his hands on the other as the sunlight, breaking through the foliage above them, dappled their skin. Soon they settled into a pose and held it, frozen in place, until the click of a camera shutter pierced the quiet.

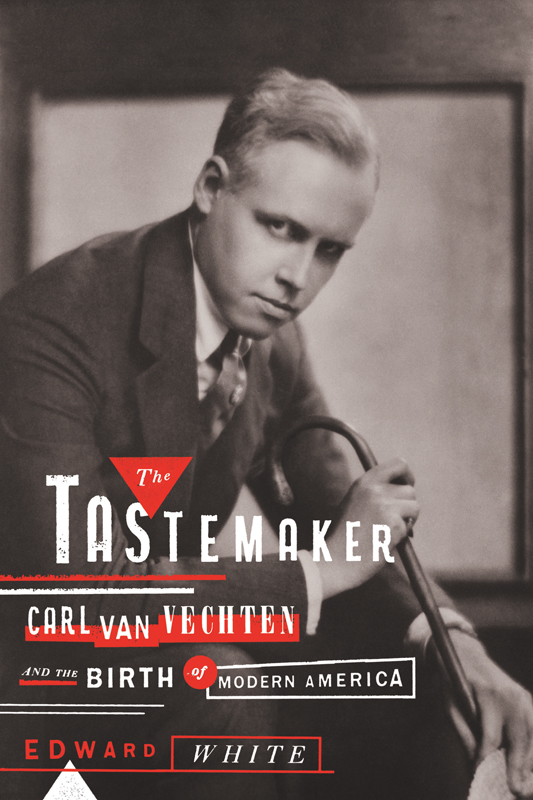

Ten feet away stood the photographer, Carl Van Vechten, a slightly stooped white man just turned sixty with thinning, slicked-back, snowy hair, high-waisted pants, and a stare as direct as the lens he held in his manicured hands. He had long been looking forward to todays shoot, which was taking place on the grounds of a friends country estate. It was an opportunity to take a moments respite from the relentless flow of happenings in his beloved New York City, the metropolis that had been his muse for the last thirty-four years of a prolifically creative life. More to the point, the two men posing for him that day were his favorite models, and it was a rare treat to have them both together like this. As he peered at them through his viewfinder, his greatest obsessions snapped into focus: the splendor of male bodies; the wonders of racial difference; the preciousness of a life lived in the service of beauty, art, and pleasure. Despite the serious expression that gripped his features whenever he stepped behind the camera, this shoot, like the hundreds of others he was to do over the next two decades, was not a professional engagement; the photographs would not be bought or exhibited. It was just for fun. In Van Vechtens life, almost everything was.

* * *

Today, nearly a half century since his death, Carl Van Vechtens name means nothing to most Americans. New Yorkers may have seen it engraved on a pillar in the Great Hall at the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue at Forty-second Street, in acknowledgment of his status as a major benefactor. Eighty or so blocks uptown, he might just garner the odd flicker of recognition as a bullhorn for the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s or perhaps as the author of Nigger Heaven , a salacious novel of 1926 that unveiled the intimate lives of black Americans to their incredulous white compatriots and stoked a passion for Harlem nightlife that became a definitive part of Jazz Age New York. The books title was as startling then as it is now, and the furor it caused has frequently overshadowed everything else Van Vechten achieved.

A list of those achievements makes extraordinary reading. Carl Van Vechten was a polymath unparalleled in the history of American arts. From the 1910s onward, he was, at various times, the nations most incisive and far-seeing arts critic, who promoted names as diverse as Gertrude Stein and Bessie Smith long before it was popular to do so; a notorious socialite who held legendary parties; a controversial novelist who captured the dizzying panorama of Prohibition Era New York and topped the bestseller lists in the process; a celebrated photographer who took thousands of portraits of underappreciated artists as well as many of the worlds most famous people; a de facto publicist for great forgotten names, including Herman Melville; and one of the most important champions of African-American literature, vital in progressing the careers of Langston Hughes, Nella Larsen, and Chester Himes.

Like many legendary New Yorkers, Van Vechten was an interloper. He grew up roughly one thousand miles from Manhattan, in the prosperous, provincial town of Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He was an odd-looking boy, willowy and sallow with entrancing chestnut-colored eyes, the prominent front teeth of a donkey, and the dress sense of a romantic poet. In Cedar Rapids, the Van Vechten men, all workaholics who made their fortunes from respectable business concerns, embodied the masculine ideals of the era, ran their homes with firm-handed benevolence, and joined clubs, lodges, and committees to shape their community. Young Carl bucked the trend. If it had not been for the unmistakable forehead and jawlinetwo solid curves of bone as smooth and thick as sculpted marbleit would have been difficult to know that he was a Van Vechten at all. He was lazy in school, had no interest in politics or sports or the other manly pursuits of the day, and sublimated his unspoken homosexual desires into a fantasy world of music, literature, and theater. His one burning desire was to ditch the life of a bourgeois midwesterner for the glamour and grime of the big cities. When asked what he was going to do when he grew up, he did not name a sensible profession or an earnest vocation like the other boys at school. He knew the art of living was to be his calling. Im going to live in Chicago; Im going to live in New York; Im going to live in London; Im going to live in Paris, he declared. He wanted to see the world and have the world see him.

When Van Vechten began his urban adventures at the start of the twentieth century, the United States was convinced of its manifest destiny as a political and economic powerhouse, yet culturally it languished in the shadow of the European civilization it aimed to usurp. With the patronage of industrial magnates, museums, opera houses, and symphony halls were built in towns and cities across the country, often in eager imitation of places seen on pilgrimages to Paris, London, Florence, Venice, and Rome. Many Americans became anxious that cultural life in the nations cities was drab and derivative, a pale imitation of European traditions. Others feared that the urban way of life was simply inimical to the American project. In his hugely popular book of 1885, Our Country , the Congregationalist minister Josiah Strong expressed the fears of many socially conservative Americans when he identified the city as a serious menace to our civilization because of its multiethnic populations of young, single people led astray by godless entertainments and fleshly pleasures. When the Democratic candidate William Jennings Bryan campaigned in the presidential election of 1896, he too tapped into the generic fears about an American republic run from the cities. Cedar Rapids was one of the many stops on his mammoth nationwide campaign circuit during which he railed against the avarice of Wall Street, the corruption of Washington, the un-American values of East Coast cultural elites, and all the other cancers that, in his view, were destroying traditional ideals of thrift, industry, and piety.

In the first forty years of the twentieth century Van Vechten played a vital role in helping the United States accept its cities as the fount of a new and distinctively American culture that would be envied and imitated the world over. As a critic, novelist, photographer, and promoter he valorized modern art and the cultural life of the city in the industrial age, in particular New York, a place he depicted as a modernist phantasmagoria in which any experience was possible. Van Vechten was always on the scene, connecting himself to Greenwich Village poets and Broadway legends, setting trends and starting crazes. For him Manhattan never loses its Arabian Nights glamour, said Van Vechtens friend the writer and editor Emily Clark in 1931. It is the eighth, and most wonderful, wonder of the world. For more than half a century he prowled its various neighborhoods in flashy silk shirts, rings, and bracelets, in search of sexual adventure, exotic entertainment, and the company of brilliant individuals from assorted backgrounds. His stated ambitions in life were to avoid responsibility and stay one step ahead of boredom. Whether it was an evening at the opera or a gin-fueled night at a gay speakeasy in Hells Kitchen, he did just that, immersing himself in spectacle and sensation.